The Amazing Story Of How Jimmy Carter's Love Of Music Helped Him Become President.

A Brothers and Sisters excerpt, inspired by watching President Carter's moving funeral today.

This is, unusually, my second straight post on the same subject: Jimmy Carter and his relationship with the Allman Brothers Band and other musicians. I was so moved by watching his funeral today. Last one was an essay adapted from Brothers and Sisters. This is a straight excerpt, just edited down a little. I am very proud of this part of the book, so I wanted to share more of it. As a lifelong political junkie, it was fun for me to delve into this stuff so deeply, and to spend a few days doing research at the Carter Presidential Library.

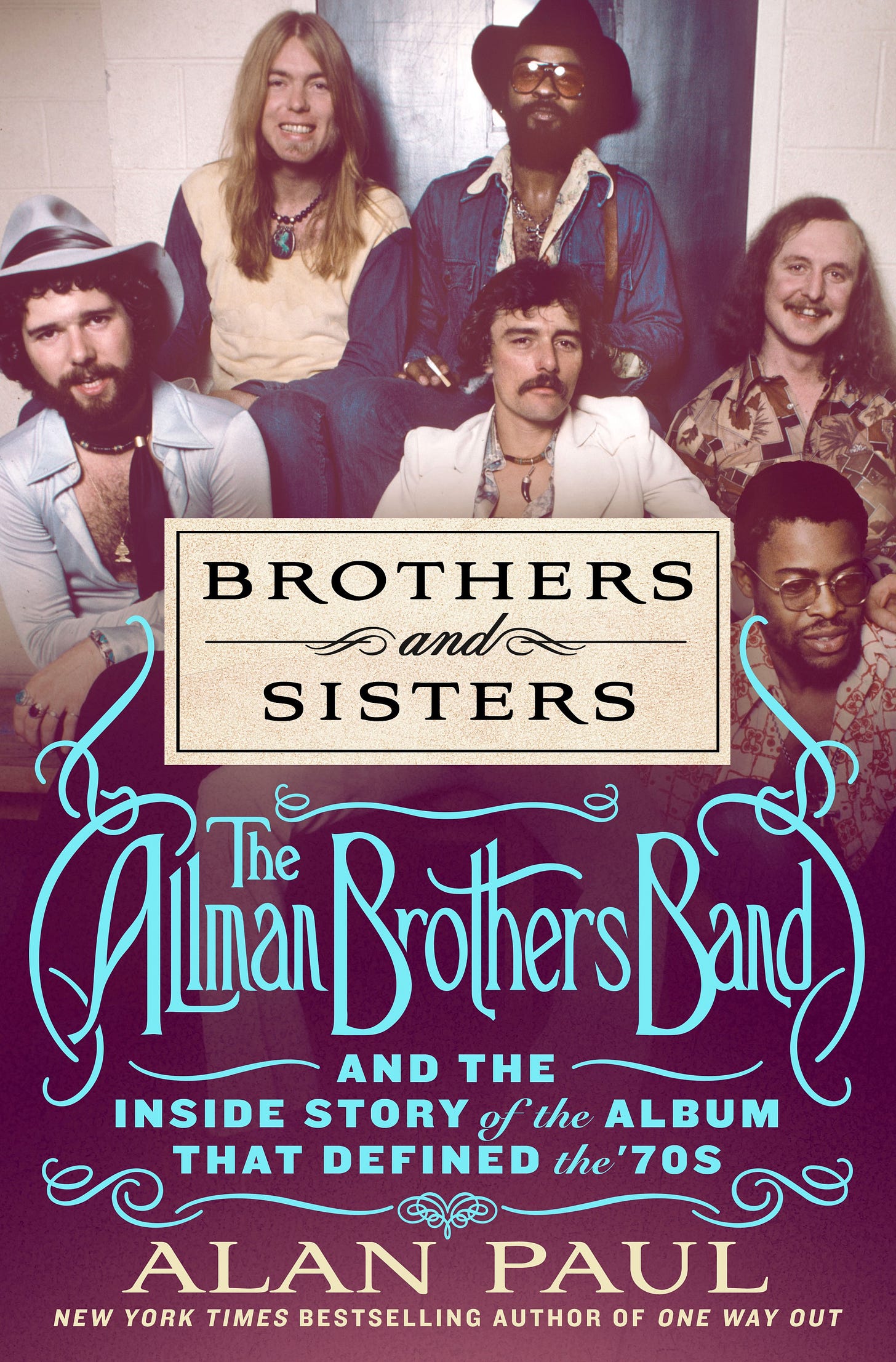

Adapted from my book Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Album That Defined the 70s, (St. Martin’s Press), copyright Alan Paul, 2023.

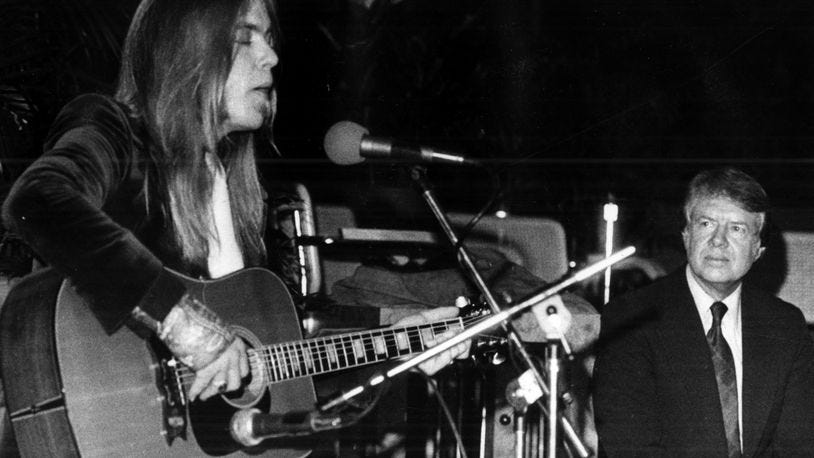

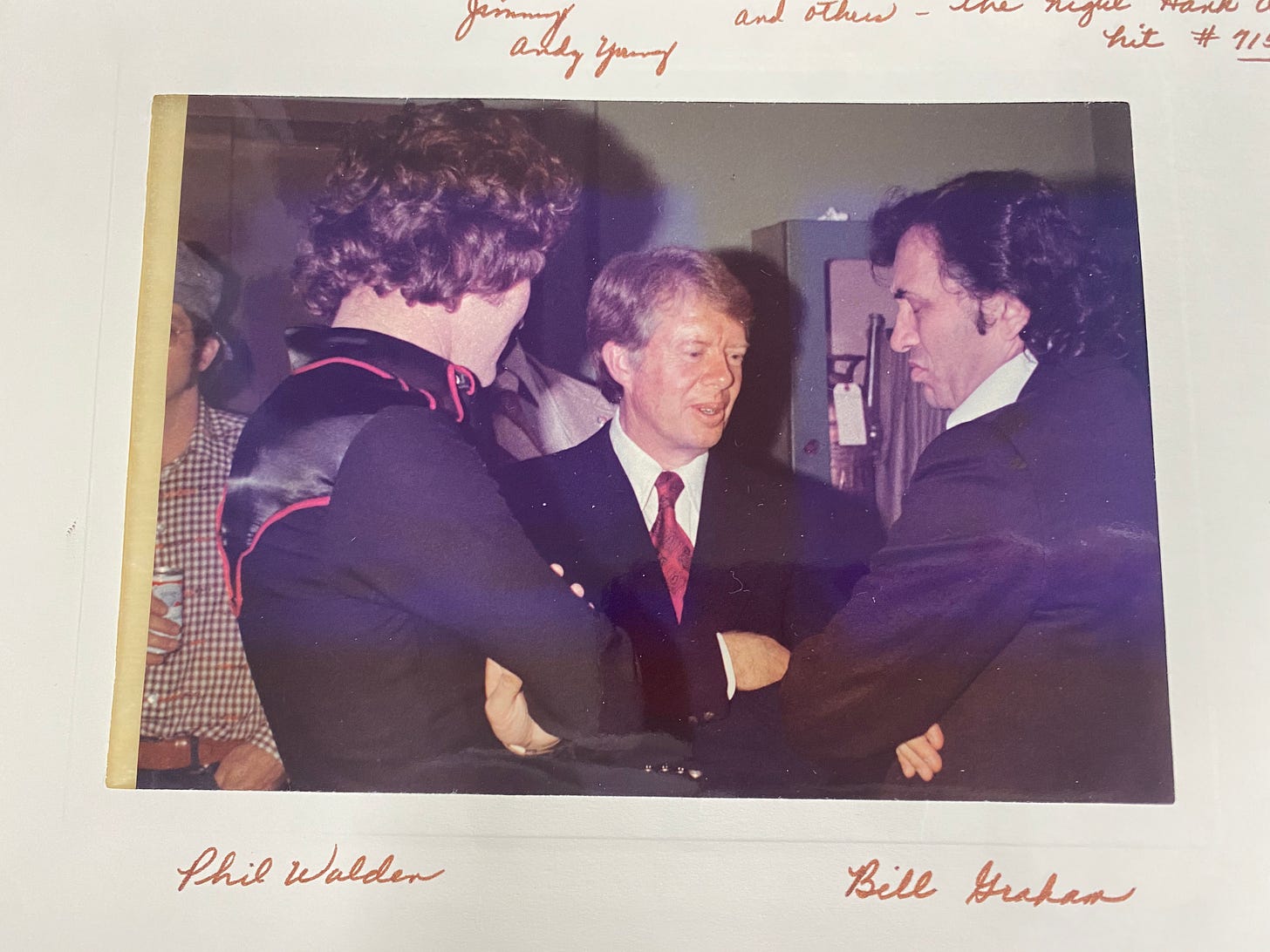

On January 21, 1974, Bob Dylan and The Band played the first of two shows at the Omni in Atlanta as part of Dylan’s triumphant return to the stage after an eight-year hiatus. Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter attended the show, having purchased 16 sixth row seats, which he insisted on paying for. Afterwards he hosted a reception at the Governor's Mansion, having invited Dylan the prior month via a hand-written note. Surprised by Carter’s invitation, Bill Graham, who was producing the tour, called Phil Walden seeking some information and guidance.

“He asked me what the hell was up with this Georgia governor,” Walden said. “Bill said Jimmy wanted to have Bob Dylan over at the Governor’s Mansion for a post-performance party, and he wanted to know if it was for real, because he had to recommend what to do. When I told him that Jimmy Carter was my buddy, Bill asked me to check this invitation out.

“I called Jimmy, who said he was a big fan of Dylan’s and he’d love for him to come. When I told him they were late night guys and they’re gonna be boozing and whatever else they’re gonna do, Jimmy said, ‘That’s ok. I want them to feel comfortable.’”

Walden and Carter’s relationship had started in 1971, when the newly elected governor stopped in Macon for a meeting, partly to discuss how best to support the state’s growing entertainment industry. That meeting was brokered by Cloyd Hall, who worked for Carter and had also been Walden's elementary school football coach.

Despite Capricorn’s success and growing importance to Macon’s economy and culture, Walden and company remained on the outside of the town’s upper crust. He appreciated, even reveled in, the governor’s attention and show of respect. Carter’s acknowledgement of the growing importance of the music business to Macon and the state of Georgia were significant because it was something few politicians had been willing to embrace.

After talking to Walden, Graham relayed Dylan’s acceptance back to Governor Carter’s office, along with the singer’s request for some “real down-home cuisine.” Carter also invited the Allman Brothers Band, Walden and other Capricorn executives to attend. Walden was joined by Frank Fenter and Alex Hodges, The Band, Graham, Carter’s three sons and some of the boys’ closest friends.

Carter says in the movie Jimmy Carter: Rock and Roll President that Dylan only asked him about his Christian faith. In five years, he would announce himself as a born-again Christian and release the religiously themed album Serve Somebody. At the governor’s mansion, he was startled and moved to realize the impact his songs had had on Carter.

“The first thing he did was quote my songs back to me,” Dylan says in the movie. “That was the first time that I realized my songs had reached into, basically, the establishment. I had no experience in that world … He put my mind at ease by not talking down to me and showing me he had a sincere appreciation of the songs I had written.”

No members of the Allman Brothers Band made it to the party, but Carter told the Capricorn crew there that he planned to run for President, and Walden replied enthusiastically, pledging his support and assistance. He’d have to convince his artists to participate, but he could be very persuasive and the Allman Brothers members tended to like Carter, anyhow.

Betts said that they could all feel the difference when he became governor and they thought, “This guy’s all right.” “It was like the sun came out in Georgia,” he said. “It was the Peach State instead of the ‘afraid to drive through it to get to Florida’ state.”

The party had ended and Dylan and the Band were on the way back to their hotels when Gregg and Janice Allman rolled up to the Governors' mansion in a limo. Gregg had been rehearsing for his upcoming solo tour and time had just run away from him. Allman said that he told the driver to pull up to the security gate to let them know they had tried to attend.

“I wanted to let the record show we appeared,” Allman said. “I got out and told the guard, who told me to wait a minute. As I was getting back in the limousine to go home, he called after me and said the governor wants to see me on the porch of the mansion.”

The limousine was waved ahead. As it approached the Governor’s mansion, which was mostly dark, with just a porch light and one inside room lit up, Allman saw a solitary figure standing on the porch.

Recalled Allman, “I saw this dude standing there in a pair of Levis, T-shirt, no shoes, wearing a white hat and thought, ‘Who’s this riff raff hanging around the governor’s mansion?’ Well, it was him!”

The governor blew Allman’s mind by saying, “Come on in. I got some new Elmore James albums we can listen to.” As they walked inside, Carter praised Allman’s songwriting and started “rattling off the lyrics” to “Black Hearted Woman,” “Midnight Rider” and “Don’t Keep Me Wondering.” The governor was clearly an educated, appreciative fan. If he was consciously wooing the rock star, he was doing a good job.

“We went in there and drank J&B scotch together and he said, ‘By the way I’m running for President,’” Allman said. “I basically laughed, thinking, ‘Okay. There ain’t been a Southern president in how long, but you think you can be the one?’”

Allman thought it was absurd to think that his governor - this guy in the T-shirt sitting next to him sipping scotch and listening to Elmore James - would ever become President of the United States of America. But he truly liked Carter, admiring his gumption and his “just folks” appeal. He was ready to assist this Sissyphian effort.

“What impressed me is not just that he cared so much about music - he knew all these lyrics - but also that he was a good guy,” Allman said. “It was easy to sit and talk to him.”

How many other governors would invite Dylan to a post-show party and how many would Bob actually accept? Was there another important politician, Allman wondered, “who would not care about the image of hanging out with people like us?” That kind of loyalty deserved to be returned, so when Carter said he “may need some money down the road” Gregg promised to bring the request to the rest of his bandmates.

“It was a friendship thing for me,” Allman said. “I liked the guy, and if he told me he needed money to open used car lots, I probably would have helped him.”

The importance of such fundraising was amplified in the 1976 presidential campaign, which was the first to be run under new campaign finance rules resulting from the Watergate scandal. They limited individual donations to $1,000 and also authorized Federal matching funds, which meant the government would give a dollar for every dollar raised within certain limitations. Raising tens of thousands of dollars in one night at a concert - which would then be doubled - would be a huge advantage.

In Walden's view, new thinking was particularly required on racial issues, where he was embarrassed by notorious segregationist Lester Maddox, who preceded Carter as Governor after defeating him in the 1966 Democratic primary. Maddox was nationally infamous for being a vicious racist. In 1964, he threatened Black activists with an ax handle when they tried to enter his Atlanta restaurant, a photo of which was seen across the country. He closed the restaurant rather than integrate. And while Carter did not select Maddox or run with him on a ticket, the former governor remarkably served as the new governor's Lieutenant Governor, a position he ran for after being limited to one gubernatorial term

“I was so sick of racists like Lestor Maddox representing our state and people thinking I was on board with that when I traveled anywhere and they heard my accent,” Walden said. “I’d get in a cab in New York and the driver would hear me talk and say, ‘You guys really know how to take care of those people down there.’ That repulsed me.

“Civil rights - black folks rights - were always a big thing for me. They shared their culture with me, and my whole career was built on my relationship with Otis Redding and people like Joe Tex and Percy Sledge. I wanted someone who more represented my values to be visible to the world.”

In 1964, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter were alone amongst their fellow congregants who voted to admit African-Americans into their Plains Baptist Church. Maddox on the other hand had refused to allow Atlanta resident Martin Luther King Jr. to lie in state in the Georgia State Capitol following his 1968 assassination, prompting both outrage and widespread support, deepening the state’s racial divides.

“When I got involved with Carter, I was preaching the gospel,” Walden said. “I just thought [he] was gonna be honest and straight and we will be able to be proud of our President and of our heritage again. I just believed in him.”

Carter was a nerdy, cardigan-wearing straight A student who left his position as a US Navy nuclear physicist to return to Plains, Georgia, population 650, to run the family peanut farm. He was an unlikely leader of the counterculture, but in his own odd way, that’s just what he became. Carter became the figurehead for a raggedy bunch of Southern musicians and promoters who wanted to be respected and taken seriously. They did not think the world would adopt their vision, but some of them believed, similarly to Walden, the former governor provided a real opportunity to make progress on issues important to them. Nineteen seventy six was just a little more than decade after passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which were arguably the most important statutes ever passed in the nation’s efforts to guarantee rights to all of its citizens and become a true democracy.

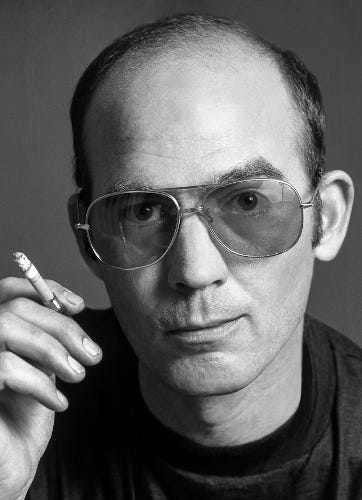

Carter received another unexpected boost in the youth market from Hunter S. Thompson. The “gonzo journalist” had a huge following, writing for Rolling Stone and was then riding high on his books Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Fear And Loathing on the Campaign Trail, which covered the 1972 presidential campaign. Thompson almost accidentally heard the Georgia governor deliver what he called a “king hell bastard of a speech” at the University of Georgia Law School’s 1974 celebration of Law Day.

Thompson was traveling with Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, who was scheduled to give the event’s keynote speech in Athens. They had spent the previous night at the Governor’s Mansion, where Kennedy found Carter, whom he was meeting for the first time, to be oddly unfriendly. What he didn’t know was the governor had been secretly running for president for 18 months and assumed that the Senator would be a primary opponent. He also ”thought Ted wasn’t as smart as his brothers and believed that his poor response to events at Chappaquiddick - where in 1969 Kennedy had driven his car off a bridge and fled the scene, leaving his young woman passenger to die - should disqualify him from the presidency,” writes Jonathan Alter in his Carter biography, His Very Best.

At the last minute, Carter changed his mind about letting his potential rival fly to Athens on his plane, sending him rushing out in the morning to make it there in time. Arriving at the luncheon and realizing that his prepared remarks were too similar to the keynote speech Kennedy was set to deliver, Carter went to an adjoining room and quickly wrote out some notes. Then he gave a speech that unsettled the conservative legal establishment seated in front of him while thrilling Thompson.

He uncorked a 45-minute speech that angered his crowd and thrilled much of the country’s liberal voters once Thompson spread the word. Carter declared himself a governor “still deeply concerned about the inadequacies of the system of which it is obvious you’re so patently proud” and attacked the lawyers for excessively punishing minor crimes. But what sealed Thompson’s affections were the sources Carter cited for his sense of social justice. First he mentioned theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, and then he added, “The other source of my understanding about what’s right and wrong in this society is from a friend of mine, a poet named Bob Dylan.”

Thompson, who had been sipping Wild Turkey in an iced tea glass throughout the luncheon, thought he must have misheard the governor, whose speech he was recording. He didn’t know much about Carter or his record as governor, but he was wowed by the oratory and by Carter’s willingness to deliver it mostly off the cuff in front of a hostile crowd. Thompson called the speech “the most eloquent thing I have ever heard from the mouth of a politician” and began urging Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner to get behind the nascent Carter campaign. Thompson’s advocacy also had a profound impact on the young political reporters who revered him, and whose attention and favorable coverage the Carter campaign badly needed to be taken seriously.

Adapted from “Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Album That Defined the 70s,” (St. Martin’s Press), copyright Alan Paul, 2023.

The paperback edition of my fourth book, Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, was recently released by St. Martin’s Press. It was the third consecutive one to debut in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List, following Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. My first book, Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about my experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band, was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. I am also a guitarist and singer with two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

This is one of my favorite stories about Jimmy Carter ♥️

Fascinating. And brings back memories of some of the best music ever.