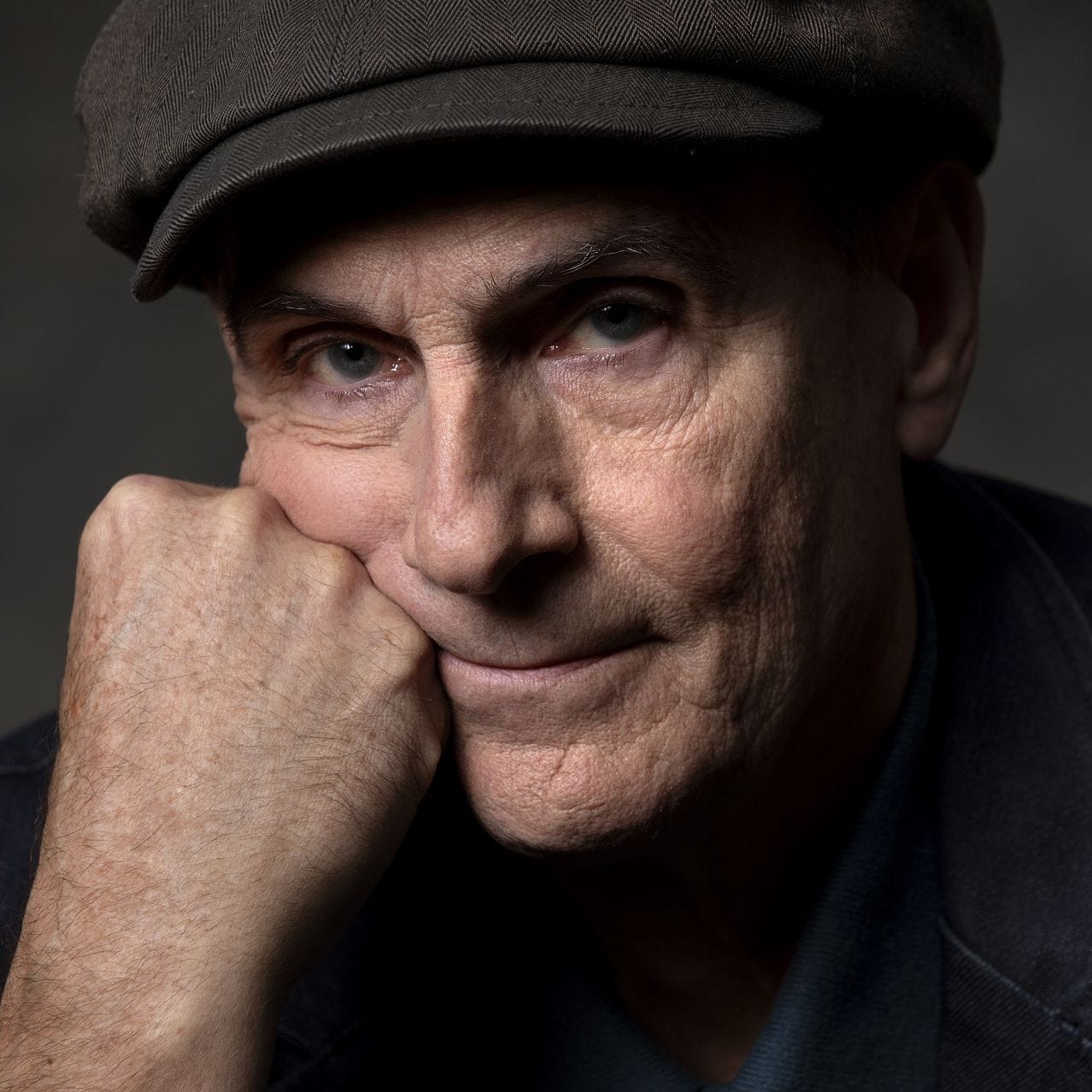

Sweet Baby James: An Interview With James Taylor

In honor of James Taylor's 75th (and 2 day) birthday, my complete 2020 interview with the maestro.

Sunday, March 12 was James Taylor’s 75th birthday. I intended to celebrate that with a post and went back to the full interview I did with him in December, 2020 to pull some highlights out. But I found the whole thing really interesting and fun, so I decided to lean it up and share it more fully. Well, that took a couple of days amidst other obligations and the tail end of Covid… so happy 75 years and 2 days to James.

My WSJ profile of James is here. And my Guitar World story is here. Both came out of this conversation. Before it picks up here, we spoke about skiing - he was in Montana and I was in Vermont, where I escaped to during the pandemic - families, and our poor teenaged kids having to deal with school and COViD. His twin sons then were freshman in college, a year ahead of my daughter Anna, who was a HS Senior. That chit chat helped establish a friendly flow, the type of thing that is harder to establish with tight time limits. I still appreciate how open ended this was. I conducted it in my car in a parking lot as it slowly became dark and freezing. I did that because cell service in my hilltop Vermont house was so unreliable.

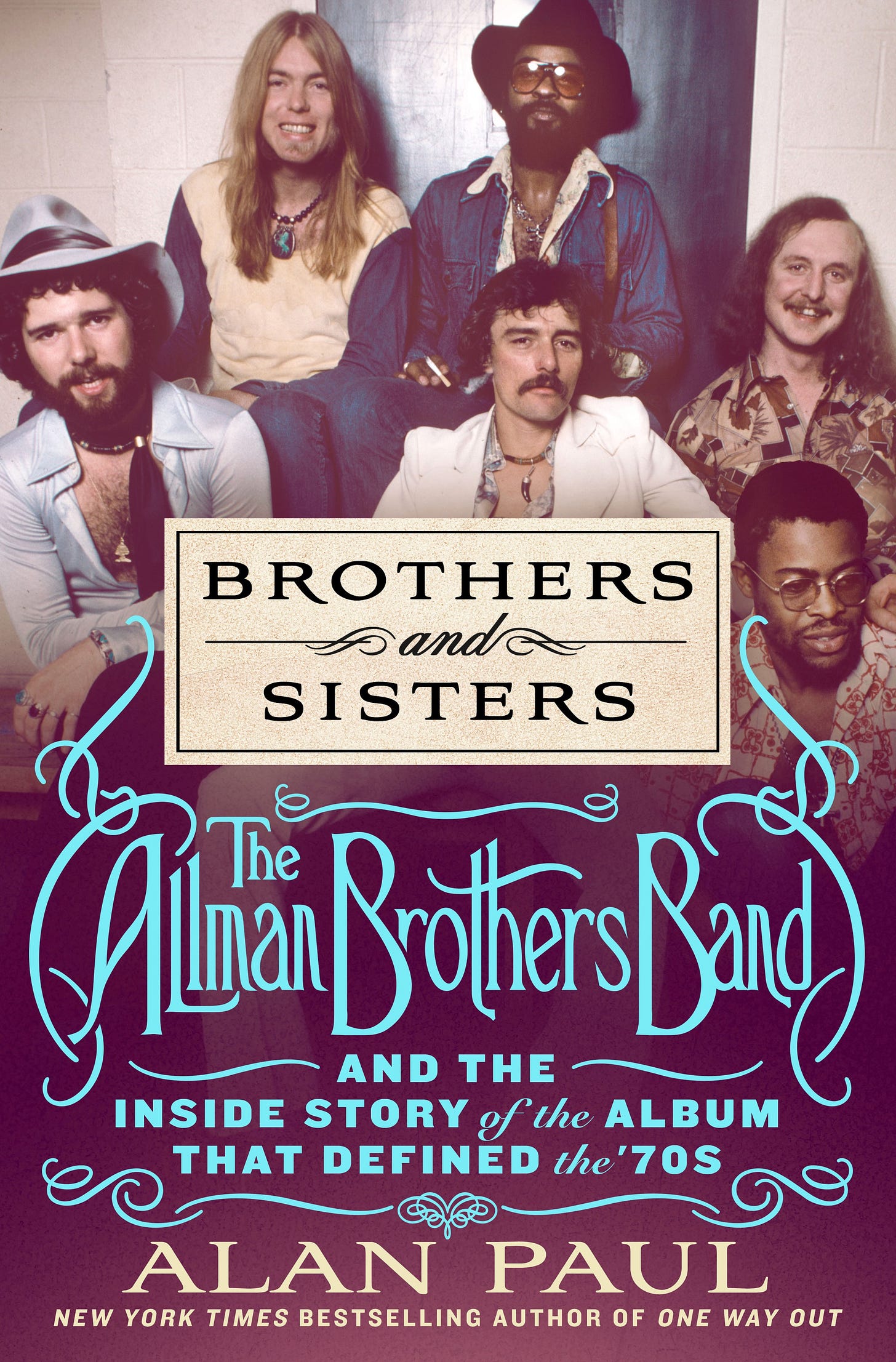

This blog is always free and open to all, so if you enjoy it, please subscribe and share. And if you’re so inclined, feel free to preorder my book Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, which will be published July 25!

ALAN PAUL: I posted a photo of you on Instagram and said I'm going to be speaking with James Taylor next week, if anyone had any lines of questioning they'd like me to address and the responses were overwhelming. It allowed me to glimpse the intensity of the role your music has played in people's lives… their weddings and funerals, love lsot and found… and the way that your music has helped them. Has that been a strange thing for you to grapple with over the years?

JAMES TAYLOR: Really, it's the whole thing that you hope for when you write a song or create art. I'm not like my friend, Carole King, who was so adept at writing for a purpose and writing for other people. My stuff is an internal thing expressed in music, and you hope that things that mean something to you will resonate with other people and have some use for them as well. It’s like we go shopping in the popular culture for our own mythology. And for our tribe, too. So we assemble things that speak for us and to us. When something that has come through you has a resonance with other people, it's the main point. It’s wonderful.

Your guitar playing has always fascinated me. It's very complex, and very different. There are elements of Blind Blake or Reverend Gary Davis blues fingerpicking, but there's also almost a classical sense. Did you base your style on anyone else?

Early on I was very influenced by what my friend Waddy Wachtel calls the great folk scare of the early 60s. It was a great time to be a guitarist and a developing musician. Because it was so accessible and there were clubs which would have open mics weekly, and there was a community of people that played and that shared things, and we were all sort of self taught. You mentioned the Reverend Gary Davis – yes! And I listened a lot to a guy named Joseph Spence, music of the Bahamas. And Ry Cooder is still my favorite guitar player.

As an inspiration or a direct influence?

I've emulated him as much as I can.

My summers in Martha’s Vineyard were to important for me musically. My mom was from Newburyport, Massachusetts. My dad was from North Carolina, and he moved the family down there, and she sort of longed for the Atlantic coast, New England - her father was a fisherman. So she would take us up to Martha's Vineyard, which at that point was like a cheap vacation, and we rented a cabin on the western end of the island. As it turned out, there was just a big folk music scene on the Vineyard. That's where I met Danny Kortchmar and a guy named Joel O'Brien, who also was a big influence on me. That's sort of the place where I developed and played music with other people. So yeah, I can't remember your question now. Guitar, right? [laughs]

You never studied classical guitar, did you?

No, I really never studied guitar at all. I mean, I always studied it, but it was a matter of taking music that I was hearing and trying to figure out how to play it. And I think the classical thing that you mentioned is actually church music. Basically, the Church of England hymnal that I was exposed to in boarding school. We weren't a church-going family, but when I went away to school I got a big dose of that stuff. And I used to transpose them onto the guitar and learning to play the guitar by playing those songs was really like a doorway into the roots of what Western music is. Those hymns are sort of 101 for Western music, and it's a great foundation.

How integral is your guitar picking to your songwriting? Do you come up with the parts as you write? Or do you come up with a basic chordal structure and lyric and then add the real part that always seem to be so perfect for the song?

Thank you. There are plenty of exceptions, but the typical thing that happens is I'll be sitting playing and just finding musical passages, like little musical wheels that go somewhere, then resolve themselves and that you can combine together to make a main theme, a release from that and then leading back into it. I'll be playing along with one of these things, and often it'll suggest a melody and a cadence that the words fit into. I'm not exactly sure how that works, but often when I'm sitting and playing a lyrical idea, a scrap of melody will develop and then I'm on my way. Sometimes I'll have a theme that I want to write about, but that often goes in its own direction without my really directing it. I really do feel as though my writing process is very unconscious.

Your guitar playing and singing both have a powerful rhythmic drive and seem so in sync with one another. Is that something that you worked on, or a natural ability?

It's just sort of develops very unconsciously. It's sort of... about the feedback. There comes a point - and you may have experienced this with guitar, too, Alan - when the stuff that's coming back at you sitting and playing is pleasing and compelling enough that you just want to do it for more. At that point, it's like you've started a fire and you don't have to work at it anymore. I'm not saying that there aren't periods of time in the songwriting process where you really do have to sit down and work, but even that is more of discovery, or like channeling something, and it's fun.

I find that as life gets more distracting with family and career and recovery -- those are the three things for me -- you have no time to write. But these sort of seminal or initial sparks of songs, the little pile of dry tinder from which you build a fire, those things still just happen on the run. Now I just use my phone and pull over or stop for a second and record a little idea. But yes, the process does have a sort of work phase to it. And I found that as time goes by, I have to defend that, make room for it and make sure that nothing intrudes.

Your last two releases featured standards. Do you have a long history with those songs?

These are songs that I played in the process of learning the guitar, and some of them I remember from early childhood. I decided relatively early on that this would be a guitar album and there's a couple of overdub keyboards on it, but basically it's just me and John Pizzarelli playing my arrangements of these songs and that turned out to be an adequate core for everything.

And John is brilliant. Did you basically play the songs and it was up to him to find his way to fit around you, or did you sit down and work them out together?

He was also an excellent editor. Often when you're playing a song with a guitar, you want to do a variation of how you support melody in the second verse, for instance, and choose different chords. And it was great to bounce those off of John and his help arranging the various iterations of these songs that I've been sort of working with for such a long time. It was great to sort of nail them down. A lot of what he did was like a musical editor.

And what a fantastic guitarist. He's so used to playing with his father, and seeing Bucky and John play together was an incredible experience.

Isn't it amazing that John lost both his parents to COVID in this past year?

I didn’t know. That's truly horrible.

Yeah. But you're right about the two of them playing together. Bucky was a real master. I can't really compare myself to Bucky, but I do have a guitar vocabulary, a kind of a style and technique that I've figured out over time, and I've definitely been able to pass that on to two of my sons. And I think that's what happened with John and Bucky, so we relate on that level, too.

That's great. I know Ben is a great player. Which other son?

I have twin boys who are 19 andHenry has picked up everything I've got on the guitar and sort of folded it into his own thing. So it's exciting to see him progressing and having caught the bug. He's got blisters on his fingers, but he still can't stop playing.

That's what you need to do. It’s part of the skill!

Listening to the standards and then going back to some of the early records it struck me how you recorded ”Oh, Susanna” on Sweet Baby James which had to be kind of a nutty idea in the middle of everything going on in 1970. And it makes the line to what you're doing now seem obvious. Did that come about from the same sort of thing - that it was a song you played and felt you could make your own?

Yeah, absolutely. But the whole thing was nutty. Just the entire enterprise was like… there was nothing premeditated or strategic about it. In the mid 60s, when I committed to being a musician, it was still very much a left turn. Now, you can study it and you can take courses in it and approach it as a career, but at the time, it was like a non-career. It was an opting out, which a lot of people were doing, How old are you, Alan?

I'm 55.

So you're born later than me and didn’t experience this. People say, for instance, when you're looking at university alumni, and how involved they are with their school, the graduating classes of like 67-72 are almost totally absent. It was a time where a lot of people wanted something different. The postwar baby bubble was 21 years old, and decided that it was going to rewrite everything, cancel everything that had happened before. And we will decide how life is lived from this point on. It was a supremely arrogant thing and destined to fail, but it did actually change a lot. It made a huge impression, particularly musically.

It was a sort of unprecedented and unrepeated time in terms of popular music. WelI, I think anything that's not a sort of classical study is essentially folk music: rock and roll, jazz, country - all folk music. A lot of people were taking that left turn, and opting out all around me. But the thing about how I approached those albums was just like any commercial aspect of it, anything that was tied to the music business as it had existed prior to right now was all sort of an embarrassment. We wanted to distance ourselves from it, and everything had to be essentially off the cuff.

Many of your songs are now modern standards in their own right. Can you see your own music in that light?

Yes. My music came together from a variety of places. Looking back on it, I see that there were various stages to my musical growth, but the first one was the family record collection with many of these songs in it. My folks had a great collection, and I thank them for that. And then the next stage was when my older brother started bringing soul music into the house. And I was turned on to Ray Charles and Joe Tex and Don Covay and The Coasters and, Jackie Wilson and Carla Thomas. The third stage was the musical community on Martha's Vineyard -- playing at open mics and sharing music with other guitar players and singers who were in that very small community.

The next step was I was in a band with my older brother in high school that definitely took me to another level. Then when I went to New York in 1966 and Danny Kortchmar and I started the Flying Machine with our friend Zach Wiesner playing bass and a drummer, that Kooch knew named Joel O'Brien. Joel was the next step in my education and he turned me on to Latin music and Brazilian music especially has a big effect on my stuff. And those Broadway musical standards, which, in my opinion, are sort of the high watermark for Western popular music in terms of its sophistication, its impact and how useful and effective the songs were. And then the Beatles were also a big influence on me: the songs of Paul McCartney and John Lennon - and Geroge, too.

Did George ask you about borrowing the first line of 'Something in the Way She Moves'? And how did you feel?

Oh, I felt hugely flattered. I had played this song for George and for Paul as my audition for Apple Records. So I think it had just sort of stuck in his mind and he didn't realize that. I think all music is reiteration. I think that we just pick stuff up and use it again. I mean, it was just 12 notes.

What was the experience like as a young singer-songwriter sitting and auditioning for George and Paul?

I can't really remember it. I have to rely on Peter Asher, who took me there. Peter had just started as the talent scout for Apple Records and I was the first signed. I arrived in London with no real idea about what to do. I had my guitar, and some songs that I'd written during the Flying Machine days, but I had no plan at all. I thought I would try to get some work in clubs, and just do the grand tour, travel around in Europe and see what I could see. Danny Kortchmar had been in a band that had backed up Peter and Gordon on their American tour and he told me to look up Peter Asher in London. I met some friends over there who were very encouraging about my music and they got me into a little demo studio I found in the phone book. I made a little demo, and I called Kootch up and asked if Peter might be interested, and he said, 'Well, I got a number for Peter, I don't know if it's still good but here it is.' It turned out that it was just the right time.

Peter and his wife really heard something in my tape, and he took me to Apple, where I played for George and Paul. And they said to Peter, you know, if you want to record this guy, sign him to the label. And that was it. It was that simple. I ran ads in the trade papers, Melody Maker and New Musical Express, for a keyboard player and a bass player, we did auditions and went to the studio. It was just otherworldly, because I was a huge Beatles fan and they were at the very height of their powers. They had surprised us all repeatedly by making the next step. I was very cynical about the music business and I thought, they’d get get bogged down or dumbed down, and break up. - that success was going to set them in aspic. But they just kept going, kept growing. So, to be in London in 1968 as the first person signed to Apple Records was really like catching the big wave. It was unbelievable.

How confident were you in yourself at that point in both your performance and your songwriting?

What a great question. I did have some kind of competence and the arrogance of youth. You know, if we didn't have those things, nobody would ever do anything, because you'd hedge your bets and back yourself into a corner and just never do anything. Part of it is that you're either bulletproof and immortal you're gonna die by the end of the week. There's a stage in our development where you're allowed to do impossible things. And that's why the military looks to people about that age. They’ll do things that if you were asked to when you were 35, you'd say, no thanks, I'll pass. I also knew that it was somehow good. It worked for me, and I was a music connoisseur, so I thought, this stuff could go somewhere, I want somebody to hear it.

The song that first made you into a star was “Fire and Rain,” off your second album. It was a long time from the release of the album until it was put out as a single - there were already starting to be covers of the song made. Were you and Peter bugging the label that this could be a hit and they should put it out? Or were you yourself surprised with it?

It’s funny. Joel O'Brien, that drummer that I credited with a major sort of step in my musical understanding, was over in England and we were spending a lot of time together and frankly getting into trouble together; he was the person who had introduced me to heroin in New York. I played “Fire and Rain” for him, and he said, “This is the song that's gonna do it for you. It's a good song, and it's accessible. Be careful how you record this one; make sure that you do a good job of it.” Peter also heard that it was something, and we actually did a recording of it before we did the Warner Bros recording. I've never told anyone that because technically it meant that Apple Records should have owned it, because we were still signed to them ,before Alan Klein moved in. I don't know if you know about him.

Oh, I know the story.

So you understand why I didn't want Alan Klein to decide that “Fire and Rain” was his! I never mentioned it, but we did a version of it then. Peter has a copy of it somewhere. And I'm glad we cut the Sweet Baby Jame version as simply as we did. The thing about that album is that we made it for $8,000 on a 16 track recorder and it took us two weeks. They gave us 20 grand to make the album with and then on delivery they would give us another 20, which is why one of the songs on the album is called “Suite for 20 G.” We just amalgamated a bunch of ideas into an album track and put it out. I can live with a project for a year and get so into it that I lose a sense of its purpose and need to stand back from it and this was the opposite. We went in and I was writing songs as I was recording them. We nailed it down so fast. I'd play a song for Carole King in the morning and we'd go straight to the studio and we'd play it for Danny Kortchmar, and then the three of us would put it down with Russ Kunkel on drums. We were just living on the surface, like one of those water striders that can walk on the surface tension of a pond. It felt like we were just right on the surface of ourselves. You know, I miss that. We're so careful now and so studious of every move. And certainly that's a good way to record, that's Steely Dan, for instance, and it's also Paul Simon -- just really focusing in getting it right. That's another kind of artistic process. But this one was really just like stepping out into traffic and getting hit by a truck.

50 years later, it obviously stands the test of time, so your instincts were right! You and Carole King both recorded and put out “You've Got A Friend” at roughly the same time, and both won Grammys for it in the same year. Obviously, it all worked out, but that’s crazy. Did either of you think to just let the other have it?

It was an unbelievably generous thing for her to do. Knowing that she had written this beautiful song that she's going into the studio to record, am I really going to have the first shot at it? Carole is unbelievably generous and felt some gratitude for me, because the song was essentially written in response to the line in “Fire and Rain” that says, ‘lonely times when I could not find a friend.'‘ In response, she wrote a song saying you've got a friend. The first time I heard it, I just had to play it. We were in the studio recording Mud Slide Slim and had already recorded two tunes that day. We had two hours of studio time left and at times like that we would often choose a cover song very much off the top of our heads and cut it. That's how I cut “Day Tripper,” “How Sweet It Is,”and “Handyman.” We'd do a quick arrangement of songs we loved and try them out.

We were so free and careless cutting “You've Got A Friend.” Listen to Lee Sklar's bass part on that song, and he's over-playing crazily, like a virtuoso bass, and Kutch also is really blowing on it. And I'm trying things vocally and the harmony parts that Joni and I put on are like a parallel fit. It doesn't really fit, but it works really well. We were just trying things, and it turned out so great. If we had asked for permission and gone in thinking we were going for the single, it would not have had that loose sound.

We liked it so much that I sort of nervously awaited Carole’s word. We played it for Carole and I said, “I know we shouldn't have done it without asking you and you need to have the first crack at this because it’s such a great song.” And she told me to go ahead. I think part of it is that Carole had been a tunesmith, and placing songs with other people was very much in her. She wasn't really set in that singer songwriter thing; she was still partially back in the Brill Building.

You mentioned Joni, and those 1970 shows that you guys did together are so great. Is there any chance of them being formally released?

They are coming out on our website. We're allowed to release those things for a short period of time, like a month or so away from the BBC. But that's a very limited window. And I don't know whether or not they'll -- I mean, I'm sure it's a possibility.

It's really wonderful music, and I just read kind of a wild story about her coming home with you and you guys going Christmas caroling with your family, which is quite an image.

Yeah, we used to do that in North Carolina. We lived in a kind of suburban neighborhood. I think we did walk around the Morgan Creek neighborhood and sang and drank.

You mentioned your brother Alex, and what an influence he was with those R&B records. I'm a big fan of his Capricorn records and the comeback he did with Blacksnake with VooDoo In You. It's really good stuff.

Oh, man, he was deeply, deeply into it. It was really all he had. I'm so touched to think that you've heard him and listened to him. That's really great.

Well, I wrote a biography of the Allman Brothers Band, so that world is sort of my ballywick.

Oh, the Allman Brothers thing -- that is a musical community and a sort of game of connect the dots. So much great stuff came out of that world. That white Southern soul world really is extremely fertile and has been really productive in terms of what it's inspired and initiated.

Yeah, andAlex brought Chuck Leavell into the Allman Brothers world. He has an important role just for that alone.

You know, I didn't realize that. Tell me more!

Chuck was in Alex's band, and they were opening for the Allman Brothers. Chuck was like 19, and after they performed, he would sit at his piano behind the curtain and play along with the Allman Brothers just for fun and the roadies heard that. They went to Dickey and Gregg and said, “You got to hear this guy from Alex Taylor's band. He's playing with you guys and it sounds like a member of the band.”

Wow. Did the Allmans have a keyboard player at that point?

Just Gregg , who always had a piano, as well as his organ on stage. You know Chuck played on Alex's album Dinnertime, which was cut around the same time as Gregg's solo debut Laid Back, with pretty much the same people, both produced by Johnny Sandlin. There was a lot of overlap in the Capricorn world, which very much included Alex for a while.

Yeah. That’s great.

You’re nominated for a Grammy on the standards album. Does that mean anything to you at this point?

It's interesting. You mentioned that “You've Got A Friend” got a Grammy in '72 or whatever. I talked earlier about our generation feeling separated from and distancing ourselves from what had come before and that the music business as it existed, was sort of viewed as having a Vegas veneer, that insincerity that seemed to be part of what we wanted to leave behind. Of course, that was arrogant too. And at the same time that I was learning about George Jones, Joe O'Brien exposed me to Sinatra in a deep way. And that was real. So it was wrongheaded, but I looked at the Grammys as being just something you turn away. I was arrogant and very dismissive of those awards. I wouldn't show up. and I didn't even pick them up. They came in the mail.

I always felt an adversarial relationship with the business side of the music. I felt as though it was just doomed to be a bad relationship. But now I have this label Concord/Fantasy that I really enjoy working with and maybe it's because there's not a king's ransom of money available anymore, and people are doing it for the right reasons now. Year after year, record sales would contract by another 15%, with the coming of digital technology and Danny Kortchmar used to say, “Well, you know, those motherfuckers ruined our business. Now let them move on and ruin some other business, and let us have it back.” What he was talking about is the fact that record companies didn't feel as though a million sales was worthy of their consideration, that what they wanted was 15 million; they wanted Thriller or Sweet Baby James or Tapestry. But everything can’t be that, and they turned a blind eye to some of the most beautiful stuff, and really weren't there for the artists in the way that they should have been. But I feel as though now that it's not polluted by so much money, there are good people in it, and I just keep coming back project after project to these same people. This is a very roundabout way of answering your question about the Grammys. I now feel as though releasing an album really is a sort of a team effort. And clearly it means a lot to the people that I work with that this is an acknowledgment of the value of the work that they've done, and so it takes on a new, a completely new feel. It's what it means to other people as well. Doesn't that sound selfless and magnanimous of me? [laughs] But I do feel differently about it now.

I know I should let you go, but I have to ask you…

I've got plenty of time for this.

Thank you. How did you come to play banjo on Neil Young’s “Old Man”?

Linda Ronstadt and I were both managed by Peter Asher and we were in Nashville, playing the Johnny Cash show at the Grand Ole Opry, and Neil was down there s recording at the same time. He asked us to come in and sing on a session and he asked me to play guitar. And when we were looking around at what guitars were available to play, there was a six string banjo. I don't play banjo, but it was fingered just like the guitar, so we gave it a try. And it did well. It was a banjo strung with electric guitar strings so I could play it.

Michael Brecker was an important person in terms of helping you...

You're mentioning all the right people! Yeah. Michael Brecker meant the world to me and to a lot of other people too. He was my sponsor. I mean, I was not a very good sponsee, and we were both busy and traveling a lot, but he definitely was the person who brought me to my first meeting. From relatively early on, when I was first able to afford having a band and hiring people, I would ask Michael to help me put together a horn section or he and Randy would come and play on a track of mine. So we had a relationship. On the album One Man Parade, he played that beautiful solo on “Don't Let Me Be Lonely Tonight.” So we had a musical connection for many years, and I would often ask him to come in and overdub three or four different parts. I was with him and he weighed like 135 pounds, his skin was gray, and he looked like he was not long for this world. The next time I saw him, about a year later, he had gained 40 pounds and he was glowing. And I said, “Man, what happened to you?” He said, “I got straight, I got clean. When you're ready to do that, come and see me.”

I think sometimes for a musician, only another musician could have that impact for a lot of reasons.

Certainly. At least initially, when you're in recovery, you want to make as much of a connection with it as you can, and after five or 10 years, sort of any recovery program will do nicely. But in the beginning, it's nice to know that people understand what it all feels like for you and what it feels like to go through the day or to be on stage and be sort of unsupported. So it was really useful to have a fellow musician, fellow addict.

Yeah. I wrote a biography of Stevie Ray Vaughan, and realized how many people he had helped in that similar way, starting with Bonnie Raitt. So many musicians came to him because of who he was, how bad he had been, and how great of a musician he remained. That had a huge impact and Michael must have been a similar beacon.

Yeah, that is really true. It's a remarkable thing. You know, early in the development of the program, people were so amazed by how well it worked at such an impossible task, and they felt as though they had stumbled on an important way to change people and there were attempts made to make it a religion, make it work in government or business. That’s why the language in the Big Book says that outside organizations, connections with religions, or churches or other outside commercial ventures, are out of bounds, that it’s just doing this thing for recovering addicts and alcoholics. But you can understand why they felt that way. Because it seemed like a miracle. Before 1935, if you were a drunk, you were finished. My brother Alex was that kind of a drunk. He was that swept away by it, that dependent upon it. Even with three people in his family in recovery, he still died an alcoholic death. But, yeah, it is an amazing thing.

Why did you decide now to do the audible memoir? Why limit the time fram and do that instead of a full memoir? Is it just more accessible to keep it limited and in your own voice?

Yeah, it's more concise to deal with that period of time. The reason we thought of it now is that my manager was looking for something for me to do as sort of a co-project to make more noise as we were releasing the standards album. He was shopping around to find something that would draw attention enough so that we could release the album and draw as much attention to it as possible. So really, the timing of it was because my manager thought it would help us sell the standards album, and the author came along from Audible at the same time. But the reason I figured to stop with the release of Sweet Baby James was -- although it does go into the future and a little bit at that point, it does go beyond 1970 -- but I figured that in my sort of promoting myself, I've become a public person and basically everything is available, from the point that I was on the cover of Time magazine in 1971 or so. And anything that's worth saying has been said. But I thought that the story of how I got to that point would make a good, concise, sort of small autobiography.

Alan Paul’s fourth book, Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, will be published July 25, 2023, by St. Martin’s Press. His last two books – Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band – debuted in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List. His first book was Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about his experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band. It was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. He is also a guitarist and singer who fronts two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

Thanks for this. He's my favourite musician and this is the best interview of him I've ever read.

Was there ever a self-taught guitarist as wondrously talented as James Taylor? Combine that guitar style with that voice, and throw in monster songwriting talent, and you've got one of the 1970s most bankable stars. And his live shows, particularly those at Cleveland's Blossom Music Center, were a summertime staple. Thanks for this terrific interview: Long live JT! --Matt Amsden