The story of "Ramblin' Man," the Dickey Betts song that finally gave the Allman Brothers a hit single.

A Brothers and Sisters excerpt on the anniversary of Ramblin' Man's chart debut.

“Low Down and Dirty is a one-man music magazine.” - Ted Drozdowski, Premier Guitar.

This week is the 52nd anniversary of the chart debut of “Ramblin’ Man,” the Dickey Betts masterpiece that became the Allman Brothers Band’s first and only hit single. The story of the writing, recording and success of the song is an interesting tale. here it is, adapted from my book Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s. If you haven’t read that yet, click and buy and please subscribe to this page!

“Ramblin’ Man” was different from anything the band had ever recorded before. The only thing close was “Blue Sky,” another major-key song with a country bounce. But “‘Blue Sky’ wasn’t all that country,” as Betts told Cameron Crowe. “It was more of that country/rock thing that was popular at that time. It could have been done by Poco or the Dead.”

“Ramblin’ Man” was much closer to being an actual country tune. Betts said the Hank Williams song of the same name inspired his initial idea, with Dickey’s lyrics adapting Williams’s “when the Lord made me, He made a ramblin’ man.” Betts originally thought he’d offer it to a country artist but was surprised to learn that he was the only guy in the band who thought it was too country for the Allman Brothers Band to record. “I was going to show it to Hank Williams Jr. and ask if he wanted to cut it,” he said.

Gregg had no issues adding the song and broadening the band’s range. “Hell, that song cooked,” he told Kirk West in 1987. He was glad the band recorded it and that Dickey didn’t save it for a solo album, as he had suggested he might do.

Decades later, after years of conflict with Betts, Butch Trucks would scoff at the song, alluding to Dickey’s initial inclination to give it to a country artist, by saying the band thought they were “recording it as a demo for Merle Haggard or someone.” But all indications are that the song was always intended to be an Allman Brothers release and that the group almost immediately knew that they had hit on something beautifully different.

“I can’t remember any discussion whatsoever about ‘Ramblin’ Man’ being too country to include,” said Leavell. “I certainly didn’t feel that way. I thought it was a marker of how great of a band it was that you could do a song like ‘Melissa’ followed by ‘Liz Reed’ followed by ‘One Way Out’—and now Dickey was pushing that out to country rock.”

As much of a departure as it was, “Ramblin’ Man” was not a new song. Betts had been working on it for a few years and had played an embryonic version for Duane. He can be heard working through the song on The Gatlinburg Tapes, a bootleg of the band jamming in April 1971 in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, during Eat a Peach songwriting sessions. At that stage, the lyrics refer to a “ramblin’ country man,” but the chords, structure, and concept are all in place. He finished writing the song about a year later in the kitchen of the Big House, the Allman Brothers’ communal home at 2321 Vineville Avenue (which now houses the Allman Brothers Band Museum at the Big House). He had written “Blue Sky” in the living room.

Betts said that he carried the germ of the idea around in his head for several years. Before the Allman Brothers Band’s formation, whenever he didn’t have a place to sleep, he’d crash at the Sarasota apartment of his friend Kenny Hartwick, whom he described as “a friendly, hayseed-cowboy kind of guy who built fences and liked to answer his own questions before you had a chance.”

“One day,” Betts recalled, “He asked me how I was doing with my music and said, ‘I bet you’re just tryin’ to make a livin’ and doin’ the best you can.’ I liked how that sounded and carried the line around in my head for about three years. Except for Kenny’s line, the rest of the lyrics were autobiographical. When I was a kid, my dad was in construction and used to move the family back and forth between central Florida’s east and west coasts. I’d go to one school for a year and another the next. I had two sets of friends and spent a lot of time in the back of a Greyhound bus. Ramblin’ was in my blood.”

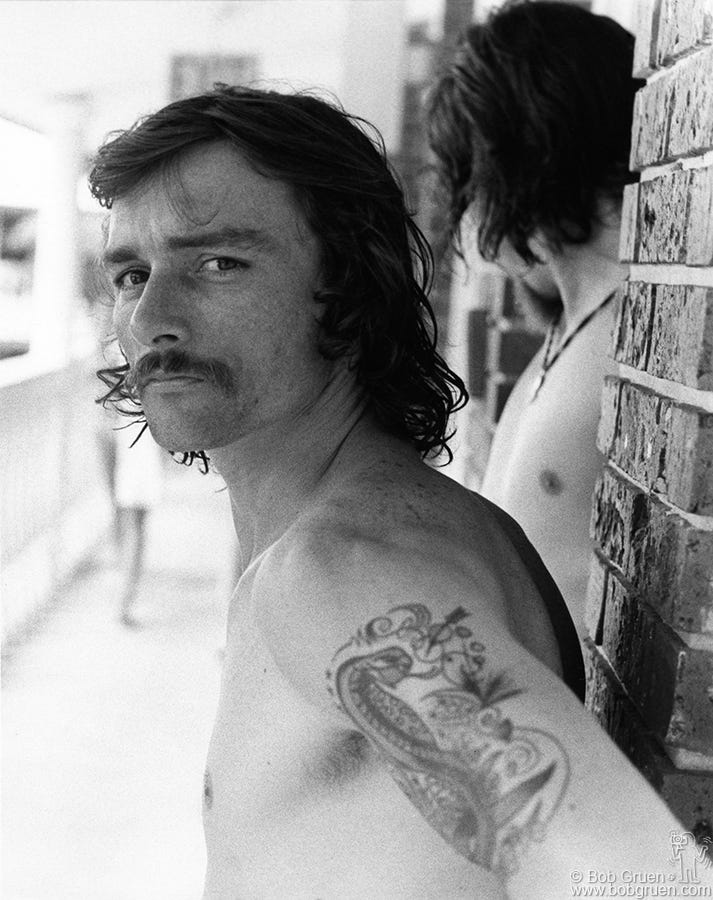

On the final version, Les Dudek plays sterling guitar harmonies with Betts, making a huge contribution to the song’s success. The two guitarists had worked out all the parts together, but then Betts decided to play them all himself, cutting multiple tracks.

Dudek was in the control room watching as Betts repeatedly came in and asked his opinion about various takes, before finally just saying, “Why don’t you just come out and play?” Dudek said that he walked out to the recording floor and they played their harmonies live, with Oakley “staring a hole” through him. The sight of another guitarist playing with Betts seemed to hit Oakley hard. “That was very intense and heavy,” Dudek said.

Sandlin agreed that the entire band knew they had something special the moment Dudek and Betts finished their guitar parts. “We all knew it was really good,” he said. “The guitar playing on the song is just amazing.”

In addition to its obvious country influences, “Ramblin’ Man” also shows Betts’s love of jazz big bands. For the coda, he wanted an orchestral approach with a huge sound. The song’s instrumental section had four guitars playing two different harmonies an octave apart and Betts’s final overdub, which was a slide guitar line. “I added that long instrumental ending in the studio to try and make it sound more like an Allman Brothers song,” said Betts.

Knowing that the song needed a strong intro to “grab the listener,” Betts turned toward the string-band music he played with his family as a boy in Florida. He wrote a fiddle-style major pentatonic guitar line, which he then worked out as a call and response with Leavell.

Ramblin’ Man” were different forms of country songs recalibrated in the band’s own image. Under Duane, they were Macon-based but rooted in the cosmopolitan centers of New York, San Francisco, and Miami and playing modern, sophisticated blues rock. Brothers and Sisters established a distinctly Macon sound and vibe, one that affected both rock and country music for decades to come. The album was an immediate hit. Record World magazine reported that nothing matched the intensity of Brothers and Sisters sales since the last Beatles release. By the end of its second week, Capricorn had shipped 1.3 million copies.

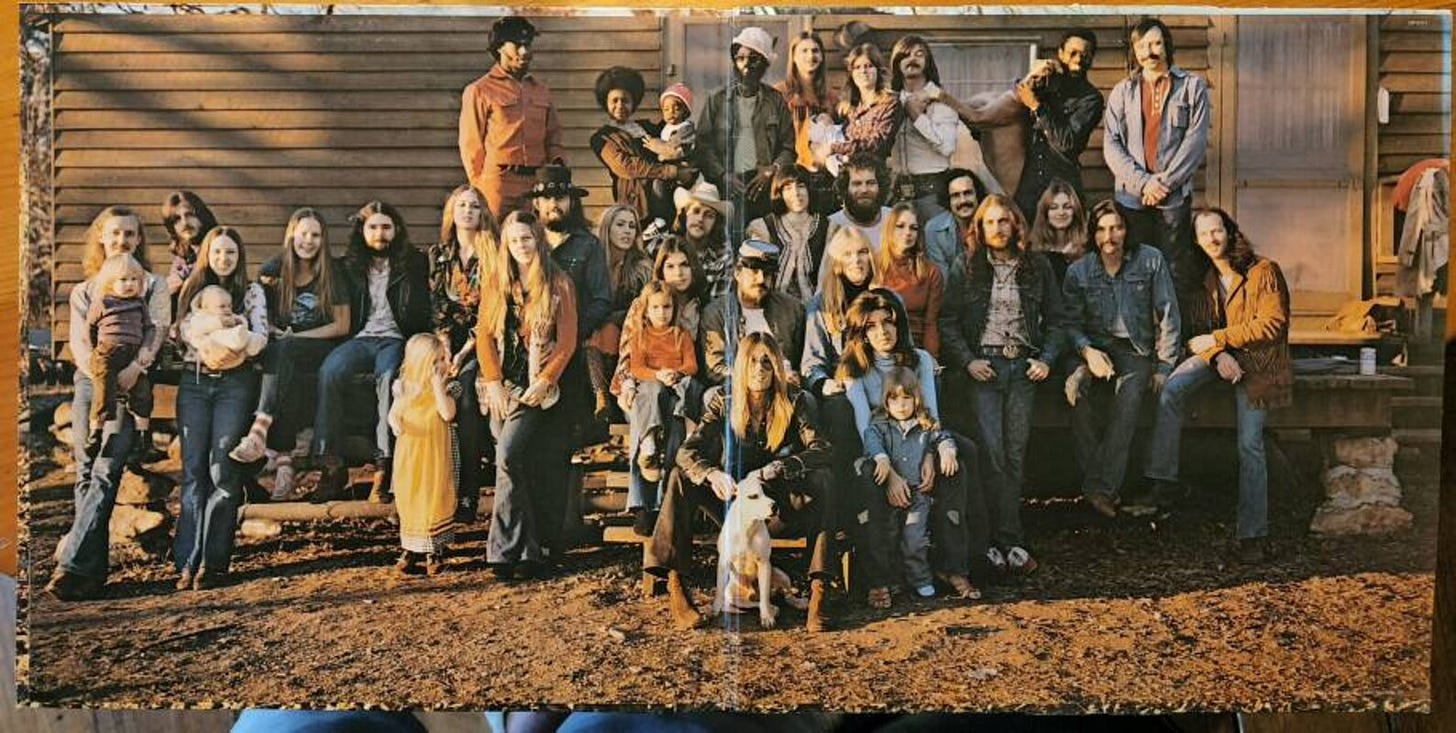

The vibe on Brothers and Sisters was unknowingly tapping into a national mood. The country sought tranquility, togetherness, and a simpler, more peaceful time after being torn apart in the ’60s by social upheaval, including Vietnam, political assassinations, and the struggle for civil rights and its attendant white backlash. The country was also grappling with the Watergate scandal that was soon to force President Richard Nixon’s resignation. The Waltons, which portrayed a fictional 1930s rural Virginia family, became the nation’s second-highest-rated television program in its second season, a month after the release of Brothers and Sisters. Little House on the Prairie, a show about the nineteenth-century frontier that debuted as a hit in 1974, also reflected this zeitgeist. These programs focused on the American ideals of family and simpler times, the same thing the gatefold image in Brothers and Sisters conveyed to audiences.

The band’s music was undergoing a similar transition. “Ramblin’ Man” was a departure not only in its country composition but also in its polished commercial sheen, which would make the song especially palatable to radio programmers. Betts was pleased that the song represented one of the first times that he and the group fully utilized the advantages of being in a studio, rather than just trying to play as they did on stage.[i]

Part of that process involved the multitracking of guitars on the track, as well as speeding the track up using a Vari-Speed, a then new tool that controlled tempo and pitch. The mixing of the song was arduous, Sandlin remembered. And it was Dickey Betts who asked him to speed “Ramblin’ Man” up. The tempo seemed too slow, he insisted. He and Sandlin worked with the Vari-Speed and made the song faster.

Sandlin finished mixing the album and asked everyone to come listen before he sent it to New York to be mastered, the final step in the recording process. Betts never showed up, but about a week later, he finally came over to listen to a test pressing of the album. As soon as he heard “Ramblin’ Man,” he started screaming, “That’s too fast!” Never mind that he himself had set the tempo.

Sandlin had to remix the song at its original speed, but when the single and album were both released just a few weeks later, “Ramblin’ Man” was the original version with the faster tempo, which also raised the pitch and stretched Betts’s voice to be a little thin, which was his real source of discomfort with it.

“They ultimately used the wrong mix—the sped-up one,” Sandlin said. “Dickey never said another word to me about it. It was hard to complain after the song became a hit. As different of a sound as ‘Ramblin’ Man’ was for the band, it worked.”

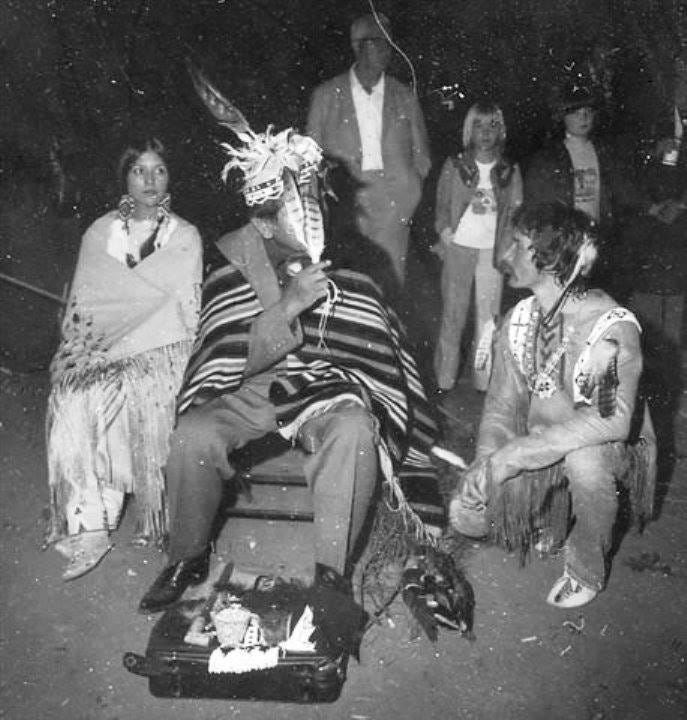

Dick Wooley, the radio promo man, had tried out “Ramblin’ Man” and “Wasted Words” with stations in Boston and Atlanta, and the choice was resoundingly clear: “Ramblin’ Man” had to be the lead single. The phones rang nonstop every time the stations played it. The Allman Brothers Band had their first true hit single. As the song began to take hold, Betts was away from all forms of communication on a Sioux reservation outside Alberta, Canada, for a gathering of the American Indian Ecumenical Council. The Allman Brothers Band’s North American Indian Foundation funded travel for more than two hundred Native Americans from various nations.

“We went into town one day and I called the Capricorn office to see what was going on,” Betts said. “I spoke with Frank Fenter and he was just elated. He told me, ‘We’ve got a hit single!’ I said, ‘That’s nice,’ and Frank said, ‘That’s all you can say?’ I was happy about it, but it hadn’t really dawned on me what it meant. I didn’t realize what a huge difference having a top-five song would make because we had never had a hit single.”

“Ramblin’ Man” made its first appearance in the Top 40 the first week of September and peaked at number 2 in mid-October; only Cher’s “Half Breed” prevented it from reaching number 1. The Allman Brothers Band had at long last crossed over to the then ubiquitous AM stations. All previous attempts at hit singles had fizzled. “Black Hearted Woman” failed to chart in 1969. 1970’s “Revival” peaked at number 92, while that year’s release of “Midnight Rider” never even hit the bottom of the charts.[1] The three singles released off Eat a Peach—“Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” “Melissa,” and “One Way Out”—all peaked at number 77. Asked why the band finally broke through, Gregg gave a very honest answer in 1974: maybe it was because Betts finally started writing and singing some songs.

“When ‘Ramblin’ Man’ became a hit everything changed,” said Betts. “The band reached a whole other level. The places we played got bigger, the crowds were huge and the money was just pouring in.”

Betts’s accomplishment impressed Phil Walden, who said, “A number one single was something totally alien to the Allman Brothers, and he did it with a country rock song! Dickey Betts put the Allman Brothers on pop radio. He walked into a very traumatic situation post-Duane and said, ‘I’ll show you what I can do.’”

The band essentially quit playing “Ramblin’ Man” after they split with Betts in 2000. Well before that, some fans cringed at the song, and the other band members at times resented being so closely associated with such an anomalous tune. But it’s just a great tune. Bob Dylan, the greatest songwriter in rock history, loved “Ramblin’ Man” and called it “one of the best songs ever written.” Betts was shocked and rightfully pleased when Dylan not only suggested they sing it together in 1995 in Tampa but also knew all the words. “I should have written that song,” Dylan told Betts.

“That was one hell of a compliment,” Betts said.

Adapted from Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, copyright 2023 Alan Paul

Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s was my third straight book to debut in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List, following Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. My first book was Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about my experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band. It was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. I am also a guitarist and singer who fronts two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

Rambling Man prepared me for the direction Dickey chose for Highway Call. Blue sky, one of my all time fave A. Bros songs also hinted at Betts country 'leanings', in my opinion. Great song and it led me into becoming a Les Dudek fan as well. thanks Alan!

Many forget that "Brothers and Sisters" was Rolling Stones's Album of the Year in 73 as well as Band of the Year. Not bad considering all the competition back then. "Ramblin' Man" as well as "Jessica" were a huge reason why!