The man who connects young love, deep soul and guitar hero Roy Buchanan.

An interview with Pittsburgh soul legend Billy Price as he releases a great new album, Person of Interest.

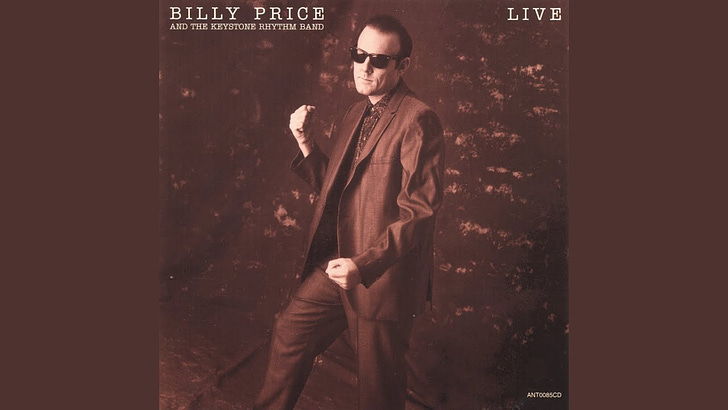

When I was a Pittsburgh kid first getting into music, there were a few local heroes that stood above the others: The Iron City Houserockers, Donnie Iris and Billy Price. Price was a local legend, a great soul singer steeped in Al Green, OV Wright (whom I learned about because of Billy) and Bobby Bland. But he also had stone cold rocker and guitar-freak legitimacy because he had toured and recorded with Roy Buchanan, the “greatest unknown guitarist.”

And Billy holds a very special place in my heart because it was on the dance floor of one of his shows with the Keystone Rhythm Band in 1988 that Rebecca and I transitioned from friends to lovers, paving the way for what is now 32 years of marriage. It changed the course of my life radically and I can easily envision some much unhappier outcomes. And I really don’t think it would have happened if we hadn’t ended up on that dance floor as Billy sang Wright’s “Precious Precious.” And we wouldn’t have been there at all, after along day and a Passover seder if good friend David Kann hadn’t insisted we go to Graffiti’s for the show. “Come on!” he said. “Billy Price!”

Rebecca and I had been friends for a couple of years and even set each other up with good friends But there we were, beers in hands, dancing together and before we knew it… here we are. Billy has a great new album, Person of Interest, which was a wonderful opportunity to interview him about his career, working with Buchanan and more.

Learn more about Billy at his site by clicking here, where you can also purhcase or stream his music. And please share and subscribe to this blog: this is a word of mouth operation!

Billy, how did you meet and start performing with Roy Buchanan? What was his status at the time - and what were you doing?

I had a good band in the early 1970s called the Rhythm Kings that was becoming popular in Pittsburgh, especially during an extended residency at the Fox Café in Shadyside. We had threeor four saxophones and played a mix of soul, rootsy rock ’n roll, R&B, and jump blues. We were somewhat similar to Roomful of Blues, who were doing the same kind of thing up in New England.

At that time, Roy was playing frequently in a roadhouse called the Crossroads in College Park, Md. with his band the Snakestretchers. The Crossroads had become a mecca for guitar aficionados based on a PBS special that had come out about Roy, “The World’s Greatest Unknown Guitarist.” One of the people who went there night after night to hear Roy was a guy from Pittsburgh named Jay Reich, and when he came home on vacations, he would often go to the Fox Café to hear the Rhythm Kings.

Based largely on the PBS special, Roy was signed to Polydor Records, and Jay eventually became Roy’s manager. By the time I got involved with Jay and Roy, Roy had released two albums on Polydor and was about to begin working on a third, with Jay producing. Polydor was interested in altering Roy’s sound to have broader appeal than the traditional roadhouse music that dominated the first two Polydor albums, Jay recruited me and another guy from Pittsburgh, bass player John Harrison, to join Roy’s band. The rationale was probably that adding a young singer and recording more rock-oriented material might help Roy to gain more fans outside of the cohort of guitar players and fans of guitar.

Did you conceive of yourself as a soul singer or a rock singer?

I aspired more to be a soul singer than a rock singer, but of course white singers who wanted to be soul singers typically got characterized as rock singers by default. I liked a lot of rock music at that time, but my first loves were always urban blues, especially Bobby Bland, and soul.

Roy was, of course, a brilliant guitarist, but one who I think lacked focus on just what he wanted to do. Do you think that’s a fair assessment?

That’s exactly what he was. He was most comfortable doing the kind of music he did on his first two Polydor albums with the Snakestretchers, which was similar to what he was doing at the Crossroads. His repertoire in the bars consisted of blues, country, and old rock ’n roll. As you probably know, he played with Ronnie Hawkins before Ronnie started working with Levon & the Hawks, who later evolved into the Band, so you can think of Roy as emerging musically from the same sort of roots that the Band came from.

Polydor and Jay pushed Roy in more of a rock direction. They did this by validating and encouraging Roy’s fixation with Hendrix, and also by encouraging his musical excesses. I specifically remember Roy playing a tasteful solo at the Record Plant when we were recording That’s What I’m Here For and Jay saying in the control room, “That’s great Roy, but can you try throwing more bullshit in there for the kids?” Because Roy did lack focus on what he wanted to do, he was susceptible to being influenced by people who had their own ideas about what he *should* do.

How was he as a bandleader?

Despite having a lot of personal problems and a complicated family life with six kids, Roy was a sweet and likable guy, and I spent a lot of fun hours listening to and talking about music with him, especially after our shows. As a bandleader, he was casual to a fault. Generally speaking, Roy was ambivalent about his own success, suspicious and intolerant of the business side of music, and much more comfortable being a member of somebody else’s band than with leading his own. The story about his having turned down an offer from the Rolling Stones when Brian Jones died may or may not be true, but if he had received that offer, he probably would have turned it down, because being in the spotlight made him uncomfortable.

As an example of the casual way he approached things, when we got together at his house to work on the songs that we would eventually record for That’s What I’m Here For, Roy would just jam with the band around a guitar riff that he had made up and wait for me to sing something—that’s the way we “wrote” songs. In a couple of cases we started with some lyrics that someone had written, but the songs that I ended up writing began at rehearsals as these sorts of jams.

He did things much differently from the way I was used to doing things as leader of my bands. My formative musical experiences came from seeing the bands of James Brown, Otis Redding, and other soul stars in the 60s, and those bands were precise, disciplined, and well-rehearsed. So the bands that I led tended to be slicker and tighter than other rock bands of the time. Once I began to perceive what Roy’s thing was all about, I became more and more committed to trying to leverage my time with Roy as a springboard to launch the Rhythm Kings beyond their status as a Pittsburgh bar band, because I could see that Roy’s jam-band ethos was likely to drive me crazy if I operated under it for too long. For various reasons, that plan for the Rhythm Kings didn’t succeed, but I quickly came to see my time as Roy’s singer as a temporary assignment.

Any particularly memorable shows or recording experiences from that era you’d like to share?

Shortly after that rehearsal at Roy’s house that I mentioned, Roy was invited to appear on the TV show Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert. We didn’t do any rehearsals for this opportunity. I don’t think we even knew what songs we were going to do until right before the sound check. I remember Roy saying, “You can sing ‘Johnny B. Goode’ and ‘I Hear You Knocking.’ Don’t worry man, you’re a pro.” Despite the fact that we as Roy’s new band hadn’t played together more than once or twice, on we went. Roy also wanted to do a couple of the songs we had recently written for the new album, and he was going to do at least one instrumental and sing two himself, “Hey Joe” and “Roy’s Bluz.” I knew Johnny B. Goode well enough but had never performed “Hear You Knocking” with anyone, and I certainly hadn’t sung these new songs we had just written often enough to really know them yet. I remember being a nervous wreck, walking around in Central Park running through the songs in my head before we taped. Not surprisingly, the songs that made the final cut were “Hey Joe” and “Roy’s Bluz,” and my first TV opportunity evaporated—which was probably for the best.

I played a lot of amazing shows with Roy and the band —Carnegie Hall, the Spectrum in Philly, the Roxy in L.A., and lots of other arenas and big-time clubs, and the more we played together the better we got. There was another phenomenal musician in that band, the keyboard player Dick Heintze from DC, who had been trained at Julliard and in his way was just as accomplished and impressive as Roy. We had high hopes for That’s What I’m Here For after we finished it, and the early reviews were good, but then Rolling Stone came out with its much-anticipated review and panned it, blaming most of its shortcomings on me. I guess I was an easier target than Roy was.

That bad review was one of the motivating factors for me to stop touring with Roy and go back to work on things with the Rhythm Kings. A new producer was brought in for Roy’s fourth album, for which he didn’t use anyone from Roy’s band. When that album didn’t do much better than ours had, Roy and Jay decided to move from Polydor to Atlantic Records. They still owed Polydor one album though, and for that, they decided to record a live album at Town Hall in N.Y. By that time, another Pittsburgh guy, Ron “Byrd” Foster, was playing drums in Roy’s band and doing most of the singing. Byrd was a fine singer, but Jay and Roy decided to invite me back to record that last Polydor album. That album, Live Stock, was a throwback to the rootsier bar-band material that Roy had done on his first two albums, and it gained a lot more airplay and recognition for Roy than our studio album had. Live Stock really jump-started my career. One song in particular, a cover of Tyrone Davis’s “Can I Change My Mind” (my idea, by the way) got a lot of attention then and still does today.

A big surprise with the passage of time has been the way that the live album, which everyone seemed to think of back then as an afterthought and a contractual obligation, is cited by a lot of Buchanan fans as his best album, while the ill-conceived studio album, which seemed a huge big deal when we recorded it, is mostly forgotten. To this day, I have a lot of gratitude to Jay and Roy for inviting me back to sing on Live Stock.

Tell me what you’re most excited about your new album, Person of Interest?

Person of Interest was produced by Tony Braunagel, the great drummer and Grammy-winning producer who leads the Phantom Blues Band, which backed Taj Mahal for many years. Tony put together a studio band for the sessions with some of the greatest players in the world. What I’m most excited about, though, is that this is the first time I’ve ever released an album on which I co-wrote every song, with no cover songs at all. I discovered that I no longer had to compete with the likes of Al, O.V., Syl, and Bobby, a practice that had been doomed to failure. This new album is more personal than my earlier albums and represents my tastes and predilections more faithfully than anything else I’ve done. A fair criticism of me throughout my career is that I’ve been a derivative artist, rehashing what other artists did first and better. With this album, I can finally put that criticism to rest.

How did Joe Bonamassa end up on it?

I wrote the song “Change Your Mind “with the keyboard player in the Billy Price Band, Jim Britton, who is my principal writing partner. When we finished writing the song, I noticed first that the title resonated with “Can I Change My Mind,” the Tyrone Davis cover that I had recorded with Roy Buchanan on Live Stock. I also noticed that the song sounded something like one of the better songs I wrote and sang with Roy on That’s What I’m Here For, Please Don’t Turn Me Away. So I had the idea that we could dedicate this song to the memory of Roy Buchanan and suggested to Tony that we should get a guitar player who knew and had been influenced by Roy’s music to play a solo on the track that would invoke Roy’s style. Tony immediately suggested Joe Bonamassa—Tony is a friend of Joe’s and has played drums with him. Of course I loved the idea and knew that Joe had publicly cited Roy as one of his strongest influences on guitar. Tony texted Joe, and he enthusiastically agreed in a matter of minutes to record the track.

When did you form the Keystone Rhythm Band?

We formed the KRB in around 1977 or 1978 up in State College, Pa. where I was going to school at Penn State to get a writing degree in the English department. I had been sitting in from time to time with an existing band that was breaking up, and we decided to form a new band. Eventually, just like with the Rhythm Kings, we started playing in Pittsburgh, became popular here, and ended up relocating to Pittsburgh, where we picked up some of our great players such as Kenny Blake, Eric Leeds, and Don Aliquo on sax, and later Glenn Pavone on guitar, who moved from Richmond to play with us.

Did the music you guys started performing, including songs by soul greats like OV Wright, Otis Clay and Syl Johnson, represent your real musical passion?

No doubt, yes. For me it started with Al Green. Stax, as a label and a studio in Memphis, was starting to wane when Al Green emerged, working at Royal Studios with Willie Mitchell producing, and the Hi Records sound became my favorite style of music, both as a singer and as a fan—Al Green, O.V. Wright, Otis Clay, Ann Peebles, Syl Johnson, and lesser known artists such as Quiet Elegance, George Jackson, Jean Plum, and others.

Looking back on those days now, I think that the fan in me may have stunted my artistic development. With the KRB, we did a lot of cover songs and probably didn’t put as much time and effort into writing songs and developing our own sound because the fan in me was content to just cover songs by the Hi artists and others. It’s true that the songs we covered were obscure enough to our fans that they identified these songs with us instead of with the original artists, and I’d like to think we brought some creativity to our interpretations, but the fact is that we were mostly performing other peoples’ songs rather than our own.

You've told me you're a "Bobby Bland" guy “just like Gregg Allman.” Talk about that, and about him.

I love the Mississippi/Chicago style of blues, but have always gravitated more to the Texas/California/Kansas City styles that usually emphasized piano and horns more than guitars, with singers backed by larger bands with sophisticated jazz-oriented arrangements. I think I bought my first Bobby Bland album when I was in high school—Ain’t Nothing You Can Do on Duke Records—and from that point on, he was always my favorite blues singer. He wasn’t strictly a blues singer, though, he was more of a blues balladeer, and a big part of his appeal for me were the great band arrangements and musical settings that were provided by his bandleader, Joe Scott, who led Bland’s band. There was a sax player in an early incarnation of the Keystone Rhythm Band named Jim “Iceman” Emminger who was a fan of jazz—Coltrane, Charlie Parker, Miles, etc.—and who didn’t listen to a lot of traditional blues, soul, or pop. He and I used to ride to gigs in my car, and when I would play Bobby Bland albums in the car, he was stunned by the hip Joe Scott arrangements he heard on those recordings. They turned him into a lifelong Bobby Bland fan.

There was a little blurb in the New Yorker a few years ago about one of the compilations of Bobby Bland’s Duke recordings that came out at that time, and the writer said that Bobby Bland had “the most gorgeous male vocal sound of the past fifty years.” That seems right to me. This past May, I was in Memphis for the Blues Music Awards, and I made it a point to say to both Bobby Bland’s son Rodd and to Bobby Bland’s widow that their father/husband had been hugely important to my life and to my career as a singer.

He had a long career after he made the recordings for Duke Records, which were largely aimed at the African-American community, and it’s likely that more people are familiar with those later recordings than with the earlier ones. Although he always had the impeccable phrasing and ability to deliver songs with consummate artistry, his voice in later years showed signs of the inevitable wear and tear that comes naturally with aging. But those early recordings in particular are among the most beautiful pieces of music I've ever heard.

You did a great collaboration with Otis Clay. Can you discuss that and what it meant to you?

I had both of Otis Clay’s Hi Records albums in the 1970s and loved them. I was working on my second album with the Keystone Rhythm Band in 1981 with Denny Bruce, who at that time owned Tacoma Records and managed the Fabulous Thunderbirds, as producer. Denny and I connected on our mutual love for soul music. Denny had grown up near Harrisburg, Pa. and remembered fondly as I did a great blue-eyed soul band from that area called the Magnificent Men. While we were getting to know each other, Denny sent me a double live album by Otis Clay that Otis had recorded in Japan with a great backup band that later backed up B.B. King. There are two Otis Clay live albums recorded in Japan from that era, and this one that Denny sent me was the first of those two—harder to find today, but to my mind much better. This album changed me from an Otis Clay fan to an Otis Clay superfan and became my very favorite recording of the early 80s. I think I must have covered every song on that album with the KRB at one time or another.

Our manager at that time, Tom Carrico, had been talking about trying to arrange some shows with either Syl Johnson or Otis Clay backed by my band. We didn’t get anywhere with Syl Johnson, but eventually I was able to get on the phone and persuade a reluctant and wary Mr. Clay to come to Pittsburgh and do shows with me and the KRB in Washington, DC and in Pittsburgh. These were some of the most exciting and emotionally draining shows I ever did in my life. I won’t ever forget the experience of singing “Is It Over?”—the title song of my first album with the KRB and a cover of an Otis Clay song—right next to my hero, trading verses and harmonizing. These first two shows kicked off a collaboration between me and Otis that included maybe 15-20 live shows over the years in various places, sometimes backed by Otis’s band and sometimes by mine, and cameo appearances by Otis and the great background singers from his band, Dianne Madison and Theresa Davis, on two of my albums, The Soul Collection and Night Work (with the French guitarist Fred Chapellier).

In 2015, I had just started talking with Duke Robillard, the great New England guitar player, about producing an album by me and the Billy Price Band. Then one day I got a phone call from Otis, who had just recently disembarked from the Legendary Rhythm & Blues Cruise. Otis said that several people on the cruise had suggested that he and I should do a full-length album together. Not surprisingly, when I floated this idea with Duke, he loved it. We were able to finish the album despite some health problems that Otis was experiencing at that time, and it ended up being the last album that Otis recorded before his death in early 2016. Needless to say, it is one of my proudest achievements.

As we’ve discussed, my wife and I got together at one of your shows – at the dearly departed Graffitis in Pittsburgh. Thank you for that. Surely we’re not the only one who’s told you this kind of story, right?

Well I would love to tell you that you and your wife are unique Alan, but I have probably been told this at least 50 times by couples at one time or another. :-) It makes me happy to have been a catalyst for the happiness of other people.

My fourth book, Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, was published July 25, 2023, by St. Martin’s Press. It was the third consecutive one to debut in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List, following Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. My first book, Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about my experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band, was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. I am also a guitarist and singer with two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

I was fortunate to see Billy and the KRB several times while growing up in the Pittsburgh area. One hell of a singer and entertainer. Also saw Roy once at W&J college south of The Burgh. Great players. Not sure if Billy played with him at that show. Thank you for your writing and I'm a big ABB fan since I was in high school in the 70's

Great interview Alan, my wife & I were just dating when we first saw Billy & the KRB, 35+ years ago. I love that he still comes back to the Philadelphia area to perform. We just saw him this past August on the 24th & of course Billy obliged to get a picture with my wife & her girlfriends celebrating her 60th. Billy always makes time to talk to you before or after the shows a truly nice guy. I finish this article & see that you wrote Brothers & Sisters, which I just read over the Summer - a great informative read for sure. So happy I found this page.