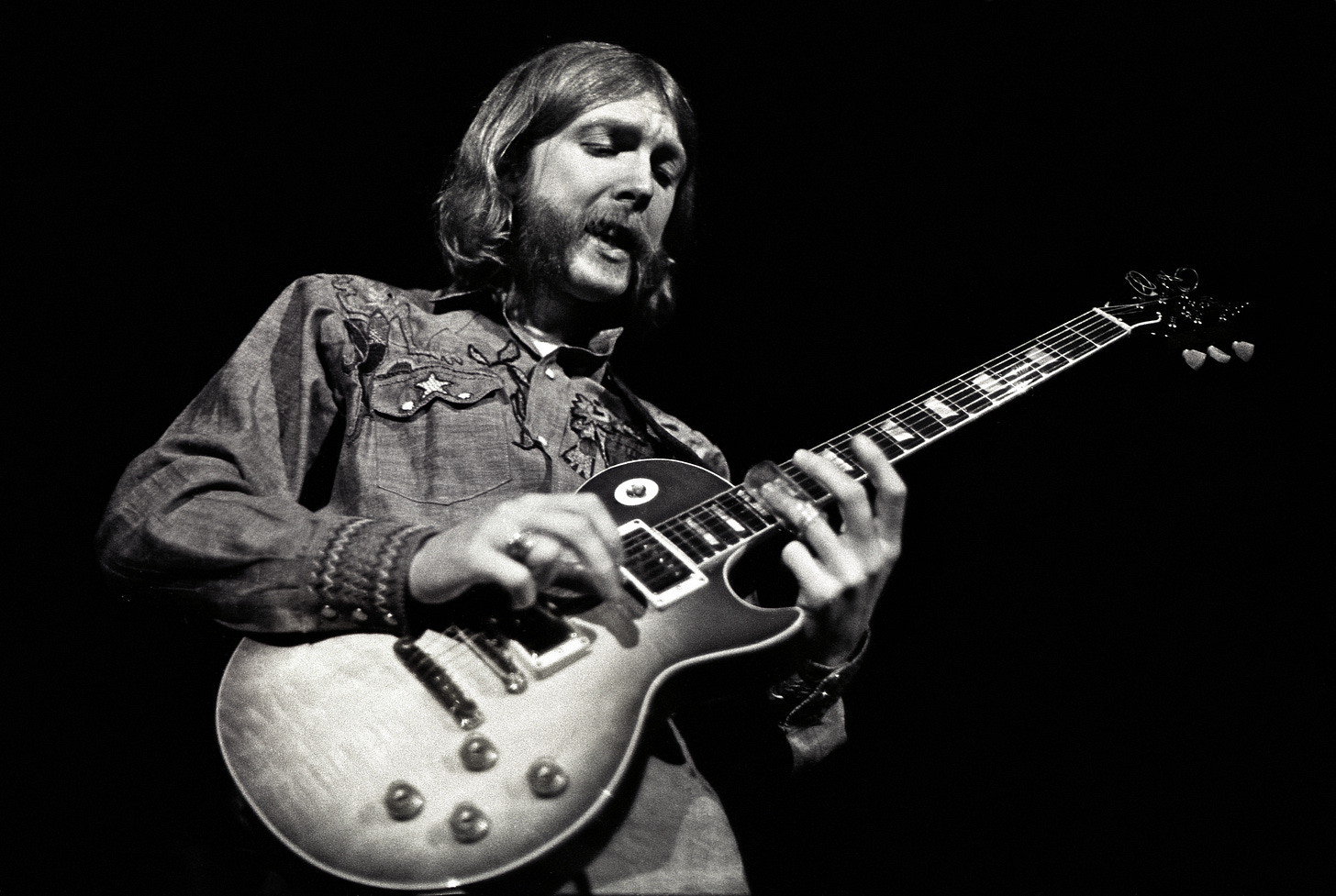

The Allman Brothers Band was born 55 years ago today, more or less.

Gregg Allman joined the rest of his brother Duane's new band in Jacksonville, Florida this week in 1969.

Adapted from Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, copyright 2023, Alan Paul. If you are reading this and don’t have that…. click and buy! And please subscribe and share this post.

Duane Allman became a first-call player in both Muscle Shoals and New York, where he worked with Aretha Franklin, King Curtis and other Atlantic artists. He could have kept going as a session player, and the other musicians at Muscle Shoals were puzzled about why he wanted to move on after such a successful start.

They “couldn't understand why I didn't want to lay around and collect five bills a week just playing sessions,” Allman told Joel Selvin. He wanted to get a band together and play live, however. “I've never been the sort of person to just lay around,” he said. “Playing on the road broadens your scope.”

“He liked that studio thing while he was doing it, but he wanted to pick!” Gregg said. “He wanted to travel. He loved the gigging business.”

Duane used his time in the studio to hone his tone and sharpen his attack while becoming more disciplined, all necessary skills to excel as a session guitarist. He learned about manipulating tone and getting the sound he wanted out of his guitar.

The producers and managers who saw Allman’s obvious talent, charisma and inner flame wanted him to lead his own band. Fame Studio’s Rick Hall signed Allman to a management contract, and they began recording solo tracks, but Duane wasn’t really a frontman and he had bigger ideas than cutting the type of album Hall envisioned. Hall recognized Duane’s brilliance, but he also quickly realized that the wild-haired, free-spirited rocker was beyond his ability to control - and Hall did not like things he could not control.

He sold the contract and those early tracks to a team of Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler and Phil Walden, Otis Redding’s former manager, for $15,000, “a steep expenditure,” Wexler noted, “because Duane didn't sing, write, nor did he have a band.” Wexler was in love with the guitarist and recognized in Duane the talent to be the next Jimi Hendrix or Eric Clapton on his hands. According to Jaimoe, the drummer who was Allman’s first hire for his new band, Wexler decided left all artist management to Walden upon learning Duane’s plan included his brother. It was nothing against Gregg, but Wexler’s lesson from observing the Everly Brothers was simple: avoid sibling acts.

“Wexler didn’t want anything to do with no brothers after whatever-what Don and Phil did,” Jaimoe says.

Walden had worked closely with fellow Macon native Otis Redding since they were teens and was bereft when the singer died in a 1967 plane crash. When Hall played Pickett’s “Hey Jude” for him, Walden knew he had found his next great talent. Listening to the wailing guitar blasting through the phone line from Alabama to Georgia, he screamed at Hall to “stop that thing!”

He had one pressing question: “Who the hell is that guitar player?”

Hall laughed and said, “He’s a long-haired hippie boy, come in here from California. He’s high on something; he’s so up there in the clouds that Pickett calls him Skyman.” Pickett’s tag combined with “Dog,” Duane’s nickname due to his mutton chop sideburns, to create the nickname that stuck: Skydog.

Nicknames be damned, Walden knew what he had to do immediately after hearing Duane’s on “Hey Jude.” He was, he said, “fixing to go down to Muscle Shoals and try to sign that boy to a management contract.”

Allman had something far grander than a trio in mind and he set about assembling his dream band, starting with Jaimoe. Born Johnie Lee Johnson and known variously as Jai Johnny Johnson or Jai Johanny Johanson when he toured the chitlin’ circuit playing with r&b stars including Otis Redding, Joe Tex and Percy Sledge, the drummer was already going by the single name Jaimoe when he met Allman.

Fed up with the bad pay and lack of respect shown to musicians by the soul singers he backed, Jaimoe was prepared to move to New York and try to make it as a jazz musician. Jazz was more than his true love, it was a spiritual quest. He long claimed God himself sent downbeat, the jazz magazine to his Gulfport, Mississippi, high school library , poring over every issue like a religious text, filling his head with knowledge of the musicians creating the sounds he loved so much. He wanted to find these guys in New York, throw his hat in that ring and see if he could cut it.

“I figured that if I was going to starve to death, I might as well do it playing the music I love,” he explains.

As Jaimoe made this decision, Duane heard a demo featuring guitarist Johnny Jenkins. As he listened, he had just one question for songwriter Jackie Avery Jr.: “Who’s the drummer?” It was Jaimoe. The drummer had backed several of Walden's clients, so Duane asked his new manager about him. Walden replied, “He plays so weird no one here knows if he’s good or not.”

Duane knew, and Jaimoe was soon on his way to Muscle Shoals, eager to meet the hot guitar player. Jaimoe was done with his situation as a drummer on the R&B touring circuit. With nothing to lose, he thought about his mentor Charles “Honeyboy” Otis’ words of wisdom - “If you want to make some money, play with a white boy” - and boarded a bus to Muscle Shoals.

Johnson walked into FAME’s Studio B and saw a “skinny little white boy hippie with long straight hair,” Duane Allman. After a brief introduction, , Duane rolled in a Fender Twin Reverb amp and the two commenced jamming. From their very first notes together, Jaimoe says, he never again worried about how much money he might make. He didn’t need to move to New York to play jazz, he could make exactly the music he wanted to make with Duane. He signed on to Duane’s project, moved into his cabin on the Tennessee River, and commenced educating his new partner about jazz, starting with Miles Davis and John Coltrane.

The African American drummer who looked like a hipster bodybuilder, with his well-developed arms and abs, tiny round sunglasses, beret and bear claw necklace, and the skinny, red-headed hippie were an Alabama odd couple if ever there was one. They formed a bond that would last forever and change the musical world.

Bassist Berry Oakley was the next to sign up for the fledgling band. The Chicago native had made his way to Florida as a clean cut teen playing bass with the garage pop band Tommy Roe and the Roemans. Oakley was an unconventional bassist, a former guitarist who didn’t see much reason to abandon melody or a full frontal attack when he switched instruments, just like his prime influences: the Jefferson Airplane’s Jack Casady and The Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh.

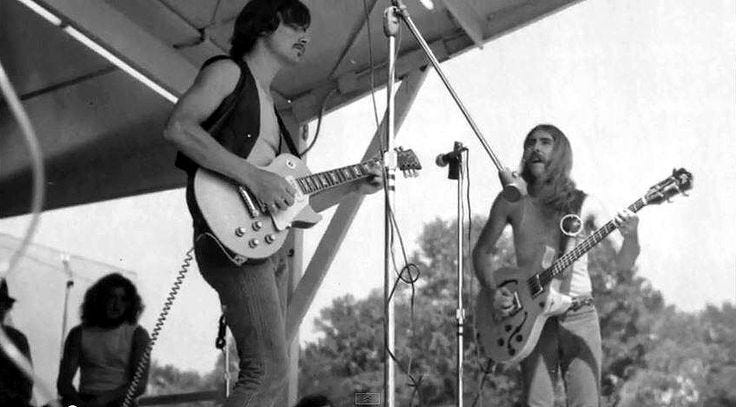

Oakley was playing in the Jacksonville band Second Coming, whose members included guitarists Dickey Betts and Larry “Rhino” Reinhardt, who would go on to join Iron Butterfly, and keyboardist Reese Wynans, who would become a member of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Double Trouble in 1985.

Oakley’s girlfriend Linda Coleman, who had hung out with the Allman Joys, introduced Duane to Berry when the Hour Glass played Jacksonville’s Comic Book Club in the summer of 1968. She was certain the young musicians were kindred spirits and her instincts were spot-on; there was an immediate musical spark between the two. They did some jamming at the time and months later, the bassist traveled to Muscle Shoals several times to play with Allman and Jaimoe. The drummer describes those jams as life changing.

Other Muscle Shoals musicians came by to check it out but “were scared” by the freeform playing and left, Jaimoe said. Duane had found the core of his band. He and Jaimoe went to Jacksonville and sat in with the Second Coming to start getting used to playing with Oakley, and immediately felt a bond with Betts as well.

Lead guitarists are like fighter pilots, surgeons, samurai warriors or heavyweight champions; they are alpha beings who generally do not seek to share the spotlight or be challenged. Duane had a different idea, even though initial earlier meetings between him and Dickey had been tense. They had each been well established for years as the hottest guitarists in a Florida club and frat party scene that included Stephen Stills, Tom Petty and Mike Campbell, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Gary Rossington and Allen Collins and future Eagles Bernie Leadon and Don Felder. Allman wanted to see what he and Betts could do together.

The Second Coming excelled at modern progressive rock, covering the likes of Cream and Jefferson Airplane. However, Betts had a broad love and knowledge of music. He had a deep affinity and talent for the acoustic blues of Robert Johnson and Blind Willie McTell and could play urban electric blues with vigor and authenticity. He said B.B. King came to him in a dream and taught him the secrets to finger vibrato. He was deeply grounded in Western swing and jazz, and loved country guitarist Roy Clark and jazz pioneers like Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt. Betts also had a family background in acoustic string music, having played ukulele and fiddle and even been a member of a banjo minstrel group long before he ever picked up an electric guitar.

Like Duane, Dickey did not graduate high school, literally running away to join the circus at age 16. He played up to 15 30-minute shows a day on state fair midways, performing Little Richard and Chuck Berry songs while doing duck walks and splits and sitting atop bandmates’ shoulders. The carnival was called the World of Mirth and the band was known as the Teen Beat.

When that gig ended, Betts eventually made his way to Indiana to play with the Jokers, a hot band on the midwestern circuit that Rick Derringer memorialized in “Rock and Roll Hootchie Koo.” (“There was a group called The Jokers, they were layin' it down.”)

Betts’ personality was as complex as his musical background. He was a student of Zen Buddhism and karate, which he used to channel and control a compulsive makeup and bursts of anger - and sometimes to commit violence. He was also a tightly coiled athlete with a short-fuse and a mighty temper. More than once, an audience member made the mistake of hurling sexual advances at Betts’ wife Dale, the Second Coming’s singer, only to find themselves in a crumpled heap at set break, when Dickey would leap off the stage, pummel the catcaller and just as quickly retreat backstage to relax with a beer. Despite such behavior, he was also a true believer in the hippie ethos of the era who would go on to write some of the most peaceful, joyful songs in the rock canon, including “Revival,” “Blue Sky” and “Jessica.”

Betts could be quiet and thoughtful, expounding on Zen Buddhism, jazz, architecture or country music, and he could disappear into his thoughts and vanish behind a blank gaze that unnerved people.

“Dickey’s a real Charles Bronson type,” Gregg Allman said. “It doesn’t take long after you meet the guy to realize that there are things he knows about himself that you’ll never know, so don’t even get close to his space. Which is fine. He’s a very intricate guy, Dickey Betts.”

Every aspect of Betts’ multifaceted musical background and Jekyll and Hyde personality would eventually be evident in his playing, which formed a large part of what came to be the Allman Brothers Band sound. Betts had a genius for inserting string-band-like melody into blues and rock songs. All of his melodic ideas were also shaped by a strong rhythmic drive that had him obsessed enough with percussion as a kid to dismantle banjos and create a drum set out of the heads.

Betts’ instinctive, distinctive melodic sense led him to consistently come up with memorable lines, which Duane jumped on, using his perfect pitch and technical facility to add harmony and counterpoint on the fly. This sympatico musical relationship helped create and define one of the greatest guitar partnerships in rock and roll history. Their partnership rewrote the book on how two rock guitarists could play together. The dynamic changed popular music

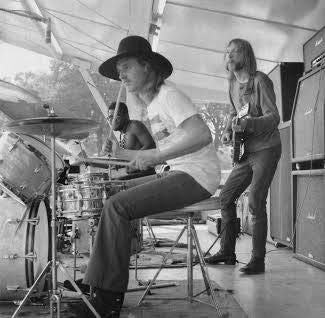

Jaimoe says that Duane discussed having two drummers from the very start and he had someone in mind: Butch Trucks, who had played a few Allman Joys gigs as a sub and with whom he’d just recorded withe the 31st of February a few months earlier. Alone among the Allman Brothers Band members, Trucks had attended college, though he only lasted one year at Florida State, distracted by the music he was playing in the folk rock group The Bitter Ind, with his high school friends Scott Boyer and David Brown. (The latter two would go on to play together in the band Cowboy.) The Bitter Ind had changed their name to the 31st of February and released an album on Vanguard Records in 1968. Vanguard rejected a second album, featuring Duane and Gregg. It was released in 1973 to capitalize on the success of the Allman Brothers Band. Much to Trucks’ dismay, it was deceivingly credited to “Duane and Gregg Allman.”

Duane drove Jaimoe to Butch’s house and introduced them simply: “Jai Johnny, my new drummer, meet Butch Trucks, my old drummer.” Then he took off, leaving the two drummers to sort things out. Jaimoe sat silently on the couch and Trucks just looked at him, finding him to be impossibly intimidating. For the first time in his middle class white Southern, born-in-1947 life, Trucks said, he “had to get to know and deal with a black man.” It completely changed him, as he wrote in the foreword to my 2014 book One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

Their initial communication came through the one thing they both knew how to do without saying much: playing music.

“From the first time we played together, Jaimoe and I just clicked,” Trucks said. “He played what he wanted and I played what I wanted and we never had to discuss it. It was just like an endless conversation.The syncopations that he brought in and his general feel for rhythm were just so fun to play with.”

With most of the pieces in place, the badn started playing at a phenomenal level.

“They were majestic instrumentally,” Walden said. “I told Duane, ‘You are musically fantastic – over everyone’s head – but you need a vocalist.’”

Sandlin told Walden how great a singer Gregg was and suggested that he was the simple answer to the band’s one missing element.

”I talked to Duane about it and he said Gregg was not reliable,” Walden said. “He said, ‘I just got out of a band with Gregg and you can’t count on him. He’s my brother and I know him better than anyone.’ I said, ‘Well, you got to have a singer.’ He thought about it for a bit and he finally made the call and brought him in.”

Gregg said that Duane called him and said, “We got it shaking down here and all we need is you.”

He arrived in Jacksonville some time around March 23, 1969 – the March 26 date they eventually settled on was nothing more than a guesstimate - and walked into a rehearsal where the band was cooking. The first song they performed together was a new arrangement of Muddy Waters’ “Trouble No More,” which Gregg had never heard. He felt intimidated to sing with a group that already had such a cohesive feel, but he passed the “audition” with flying colors. Duane’s band was now complete.

Everyone in the room knew that Gregg was a great singer, but he had recently developed into a great songwriter after years of trying. He was starting to get on a roll, developing material that would define the band’s catalog. He came armed with “Dreams” and “It’s Not My Cross to Bear,” which he had just written and demoed on Wurlitzer piano in his Los Angeles living room.

It’s difficult to grasp how someone just 21 years old could have written and sung the existential blues of “Dreams” and “It’s Not My Cross to Bear,” but Gregg had already seen some things. He reached such a level of despair living alone in Los Angeles that he contemplated ending his life.

“Just before I put the gun to my head, the phone rang,” Allman said. It was Duane calling to tell him to come to Jacksonville. All that pain and confusion came pouring out in his music. Gregg’s songwriting and singing were filled with a depth and at times anguish remarkable for someone so young.

Adapted from Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, copyright 2023, Alan Paul.

Gregg was not the only member who evinced a maturity well beyond his age. When the Allman Brothers Band formed, Duane was 22, and Gregg and Trucks were both 21. Oakley was the youngest member, not yet 21, while Jaimoe and Betts were the oldest members at 24 and 25 respectively. Despite their relative youth, each of the members were seasoned road musicians, with years of touring and performing experience.

“We were a nightclub band, not a garage band,” says Betts. “We had brought ourselves up in the professional world by actually playing in bars and that really gives you a lot more depth. My own nightclub period, from about 16 to 22 years old, was like going to college.”

After years of each of them feeling like the most serious, dedicated member of any band they were in, the six musicians immediately recognized they had found kindred spirits, not only in terms of musical vision, but simple dedication to their craft and art.

“It was the first time in my life I was playing in a band where everyone was a totally committed pro,” Gregg said. “Everyone had the same sense of self respect. We didn’t know exactly where it was going, but we knew where it wasn’t going: we weren’t going to play any Beatles or Top 40 songs just to have enough to eat. We were gonna play our music and if we starved, so be it.

With everyone in place, the unnamed band played a few informal gigs billed as a “fantastic group” along with Second Coming, and absorbing some of that band’s fan base and repertoire. That included an instrumental version of the Spencer Davis Group’s “Don’t Want You No More,” which they would pair with Gregg’s “It’s Not My Cross to Bear,” with fantastic results. Duane called Walden from Jacksonville and said, “I got it together. I got the band. Get us a place to stay in Macon. I’m gonna bring the band there and get started.”

My fourth book, Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, was published July 25, 2023, by St. Martin’s Press. It was the third consecutive one to debut in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List, following Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. My first book, Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about my experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band, was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. I am also a guitarist and singer with two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

Thank you! Huge love for the Allman Bros Band since forever. All of your writings on them puts a big smile on my face and in my heart.

Love to read about the ABB- such a magical band. There will never be another like it..♥️🍑

Thanks Alan for all you do for the musical world.