RIP Bobby Whitlock, who never stopped hating the Layla coda! Here's why. Our conversations about Duane Allman, Eric Clapton and Layla.

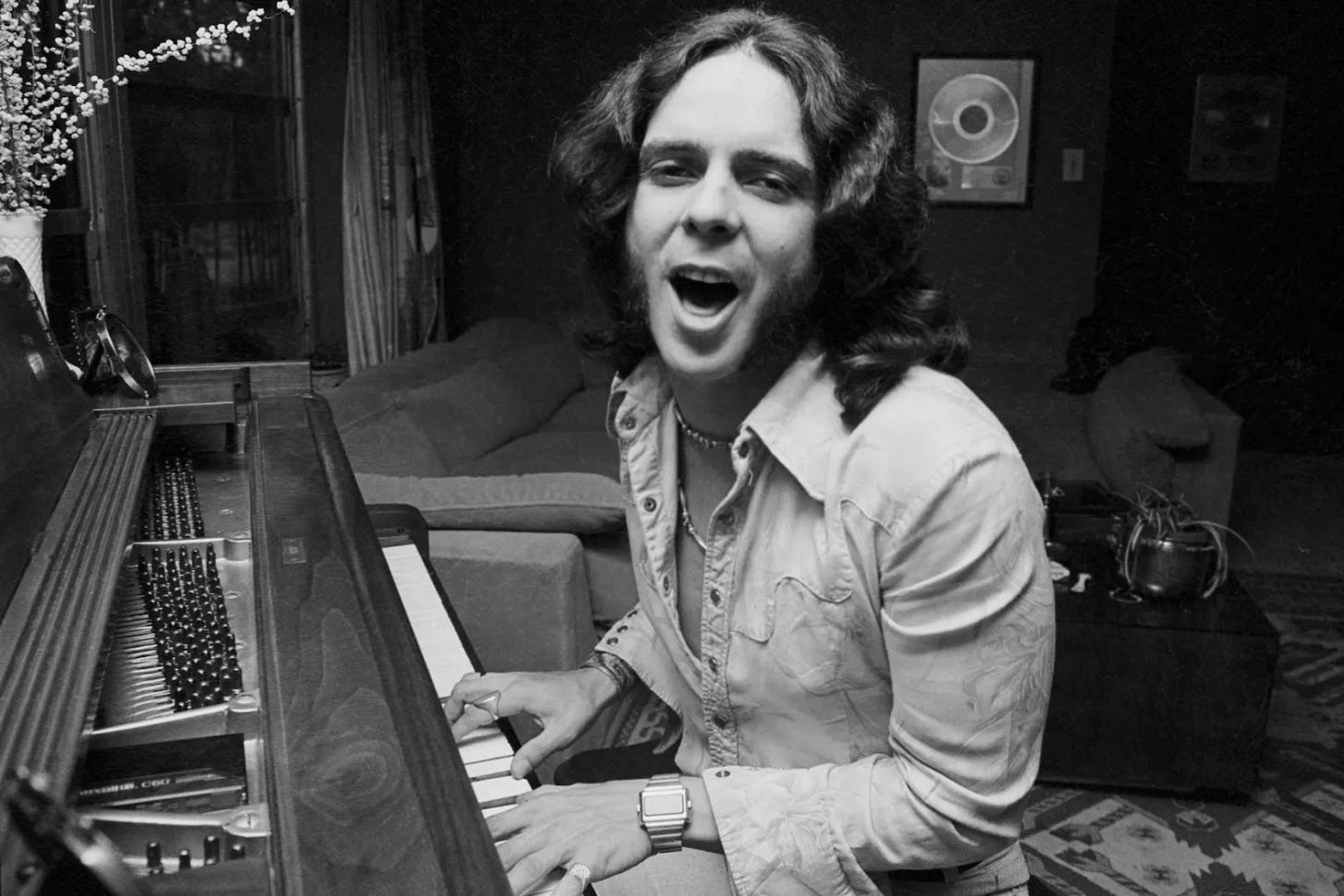

The news that Bobby Whitlock, Derek and the Dominos co-Founder and session player for George Harrison and others, had passed away at age 77 spurred me to jump on a borrowed laptop on vacation.

I was only going to share some pre-scheduled posts this week, as I sip rum and look at sand dunes, but Bobby Whitlock’s passing to the other side prompted me to get on my wife’s computer and start typing. Thgat’s also why it took me a couple of days since Whitlock’s passing to get this up.

Whitlock, a Memphis native who got to know both Duane Allman and Eric Clapton as a member of Delaney and Bonnie and Friends, was a key contributor to Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, one of rock’s landmark albums. I explored the recording in One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band, due to Duane Allman’s central involvement.

I interviewed Whitlock for the book and found him engaging, informed and pretty open, despite a prickly reputation. He also praised Duane’s paying and contribution to the album, despite sometimes talking him down over the years.

Whitlock rejected the oft-stated belief that the Layla sessions were dead in the water before Duane arrived at Miami’s Criteria Studio, while acknowledging the guitarist’s profound contributions to the album. That contention - that the band was going nowhere before Duane joined after a fortuitous meeting arranged by producer Tom Dowd, was probably the heart of Whitlock’s annoyance over the years.

”We weren’t really stagnant before Duane arrived,” he told me. Whitlock co-wrote seven of the album’s tracks, including “Bell Bottom Blues,” “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad?” and “Tell the Truth.” That may be why he found the notion of Duane saving the sessions so annoying.

He pointed out that three songs central to the album - “I Looked Away,’ “Tell the Truth” and “Bell Bottom Blues” - had already been written and recorded and “Keep on Growing” had emerged out of a jam. “Eric kept playing guitar parts and I ran out into the lobby with a yellow pad and wrote out the lyrics as fast as my fingers would move,” he said. “So we had something going and it was good, but we didn’t have enough material for one album, much less a double album. We didn’t have a plan and when Duane came on the scene, everything exploded and things just started coming.

“Duane was very, very good in the studio. Working with the finest musicians and engineers on the planet really paid off for him. When he had the opportunity to be thrust into that environment, he absorbed what was right and righteous and then used it to killer advantage.”

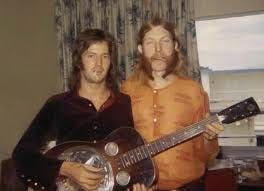

Further, Whitlock said, “We had two leaders then. We had Eric and Duane. Eric backed up and gave Duane a lot of latitude, a lot of room, so he could contribute up to his full potentiality, and Duane was full of fire and ideas. Like, he just said, ‘Hey, how about we try ‘Little Wing?’’ - that was completely his idea and he came up with the intro by himself. He just started playing it.”

Saying that it was Duane’s idea to record the Jimi Hendrix classic is itself a giant nod, much less that he came up with the opening that made it so distinctly their own, but Whitlock went a lot further in his praise of the guitarist he had first met as a member of Delaney and Bonnie and Friends.

“Duane and Eric were immediately like long-lost brothers,” he said. As soon as they met, they “started bouncing back and forth on each other and it was an amazing experience.” Most of the Allman Brothers Band were in the studio that night - except Jaimoe, who found the whole thing kind of boring and retreated to the ABB’s Winebago to smopke weed and listen to some jazz, just another reason he is the coolest person in the world. Eventually, however, “everyone else drifted away, but Duane stayed all night.”

“This thing with Eric and Duane was such a natural,” Whitlock continued. “They had the same authority, and they dug from the same well: Robert Johnson, Elmore James, Sonny Boy Williamson, Bill Broonzy.”

When Duane joined Derek and the Dominos at the Thunderbird Motel, the jamming went deeper and the brotherhood grew stronger. “One of the most amazing things I ever witnessed was in Eric’s room there,” Whitlock said. “The two of them were going back and forth hitting a Robert Johnson lick, then Elmore James and on and on. I knew I was witnessing something real special - these guys in front of me pulling all this from the deep well. I was in awe, because they were both in their early 20s and they were like two 70-something old blues guys from the fields of Mississippi running it down.”

While Derek and the Dominos were recording, Sam the Sham [Domingo “Sam” Zamudio of “Wooly Bully” fame] was recording next door in studio B. He was a childhood friend of Whitlock’s, who says it ewas Sam who suggested that the Dominos play two of the three blues classics that are on the album. “Nobody Knows You’re Down and Out” and “Key to the Highway.”

This claim of Whitlock’s is questionable. I believe that it was Duane’s idea to record at least “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,” because he and Gregg had cut a version of it a few years earlier in sessions with Butch Trucks’ band the 31st of February, the sessions eventually released under the album misleadingly titled “Duane and Gregg Allman.”

The version of “Key to the Highway” on the Layla album came out of a jam, according to Whitlock. He said that the reason it fades in, seemingly in the middle of the song, is that “Tom Dowd was in the toilet and it was one of the few times during these sessions that tapes weren’t rolling. He came running out of the can, screaming, ‘Push up the faders! Push up the faders!’”

No explanation of why they didn’t just start over, but that’s the way things rolled and why we love this off the cuff music so much. Dowd was adamant to me while “there have been a lot of stories about how much drugs these guys did, we started sessions every day at 2:00 and everyone arrived clear eyed and ready to work.

“Even in his wildest moments, Eric arrived at the studio on time with his instrument in tune, ready to play — and he would give absolute hell to anyone who didn’t. Eric and Duane shared that. They didn’t know each other from Adam before the sessions began, but they were both taskmasters. They didn’t give a damn what anyone did on their own time, but when they were in the studio, it was their time, and you better be ready to go.”

Whitlock acknowledged that the band had asked Duane to join, an offer he contemplated, missing some Allman Brothers Band shows to perform twice with Derek and the Domonos. Whitlock told me, rather ridiculously, that it didn’t work because as great as Duane was in the studio he struggled with on stage improvisation, but was right on in his assessment that it wouldn’t have worked because, “Duane was a leader himself.” Duane Allman was wasn’t cut out to join someone else’s band, even if that someone was his hero, Eric Clapton.

While Butch Trucks and Dickey Betts fretted over Duane’s daliance with the Dominos, Jaimoe says he never worried. “One monkey don’t stop no show,” he told me. “I played music before I met Duane and I was gonna play it after.” But, more to the point, he didn’t worry because he was confident that their band was better than Clapton’s.

”When Duane got back, he figured out what I already knew: ‘Shit, Eric Clapton should be opening for us,’” Jaimoe told me. “That was the kind of attitude we all had and it was probably the best thing we had going for us. I just simply thought Duane had more going playing with us than with Eric. He had put together this band exactly how he wanted it and I think playing those dates with Eric helped him realize that.”

Duane was, however, on hand, when Derek and the Dominos reconvened to add a coda to”Layla,” a decision that rankled Whitlock, who was still fuming to me about it over 40 years later.

“To this day, I think adding the coda was a big mistake,” he said. He never liked the part, didn’t think it fit an already great song and was extremely bothered by the fact that he said drummer Jim Gordon, who claimed authorship, had stolen the song from his ex-girlfriend, singer Rita Coolidge.

“When I was still with Delaney and living in the big house they had in LA, they had a guesthouse up on top of the hill. I went up there and Jim, Rita Coolidge, Bobby Keys and some other folks started messing around on this melody on the piano and asked me to join in,” Whitlock said. He claimed he begged off, saying “That for sure ain’t rock and roll.”

“They wrote this song called ‘Time,’ which was later recorded by Rita’s sister Priscilla —and that was the melody to the ‘Layla’ coda,” Whitlock said.

This was the first time I had heard this claim, and I think it is clearly true. Listen for yourself below. Rita Coolidge discussed this in her book, Delta Lady, which came out in 2017, three years after One Way Out. I should’ve made a bigger deal of this, tbh.

“It was Jim’s brilliant idea to stick it at the end of ‘Layla’ and I just did not think it belonged there,” Whitlock said. “It was tainted goods, and it completely taints the integrity of this great song that Eric wrote himself from the heart. It was stolen goods. He took it from Rita Coolidge and didn’t give her credit. I could hear how it would work, but I thought it was an ego trip on Jim’s part and I was like, ‘What am I going to do when we play it live - walk over and play drums?’ Of course, it became a moot point, because we only did it live once, with Duane in Tampa [on 12/1/70], and it ended on a suspended note - no coda.”

“I did not want anything to do with the coda so Jim played the drums and came back and played the piano, but he’s not a piano player, so there was no feel to it, and Tom asked me to put another piano on there. In the Language of Music movie [a documentary about Dowd’s career], when Tom pulls the tracks to ‘Layla’ up individually, there is a track labeled ‘support piano’ and he says, ‘I forgot about that.’ That was me. Tom mixed it in to give the piano part more feel and life.”

I appreciated Whitlock giving me so much time and insight into the recording of Layla, all the more so now that he’s gone. Rest easy, Bobby. Sending best wishes to his wife and longtime performing partner Coco Carmel and to his entire family.

If you haven’t read One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band yet, by all means click the link and do so!

Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s was my third straight book to debut in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List, following Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. My first book was Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about my experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band. It was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. I am also a guitarist and singer who fronts two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

Thanks Alan, great writeup. Bobby did have a reputation for being prickly, but I he was open with me as well when I interviewed him a few years ago, and told essentially the same story about Key to the Highway: "We has a standing rule that if anybody started playing that the tape machines would be running at all times. That was my idea as well. Tom was in the bathroom when we started to play it and the tape was not running when we started. Tom came running out of the bathroom still pulling up his pants shouting, "Push up the faders!" "Push up the faders!" That's why it fades into the track."

While I have no doubt Bobby said it, it is a bit unfortunate that he perpetuates an inaccurate image of blues musicians ("hitting a Robert Johnson lick, then Elmore James... like two 70-something old blues guys from the fields of Mississippi running it down.”) RJ was 27 when he died, EJ was 45, and while both were born in the Delta RJ spent a lot of his life in Memphis, EJ got to Chicago as soon as he could, and neither spent time in the fields once they were adults and could get gigs. The image of blues artists as 70-something guys comes from the fact that many blues artists were "rediscovered" (of course they never thought of themselves as lost!) during the 1960s blues revival, so all the hippies "discovered" them when they were old. But most of the blues artists were in their 20s when they were first recorded and had their most active careers.

As I said, I am sure Bobby said it!

Hope you enjoy the rum and the beach!

Brennan

Excellent! Thanks for taking a short break from your vacation to share your knowledge.

Bobby Whitlock will hopefully get more credit for his contributions to the Layla album.