Of course Jann Wenner is a buffoon!

Some thoughts on the unsurprising downfall of the Rolling Stone founder and editor, including a Brothers and Sisters excerpt.

You’ve probably heard by now that Rolling Stone founder and editor Jann Wenner blew up his 55-year career in a New York Times interview last week, promoting his new book on seven music “masters”—all white men. He has since been widely mocked, been kicked off the board of the Rock n Roll Hall of Fame (which he co-founded) and been losing speaking engagements around his book. None of this is particularly surprising to me and wouldn’t be to anyone who read Joe Hagan’s excellent biography Sticky Fingers, or just has been paying a lot of attention to Wenner’s career over the years.

I can’t really overstate how important Rolling Stone was to me in my early years, as a music and pop culture-crazed kid in Pittsburgh. I didn’t know from Crawdaddy or Creem or anything else. Rolling Stone was it; my portal into what the cool kids thought, read, listened to, watched. It warped me in lots of ways and created some prejudices that I regret ever developing and had to work out of, but it also shined a light on what was possible and helped me learn about great writing and reporting, because there truly was a lot of it in the magazine, as well. Rarely is something simply black and white.

At the start of my career, becoming a Rolling Stone writer was the height of my ambition, though I barely knew how to make that happen and it faded, then vanished as a goal at some point. I’ve done some writing for them over the years, lastly in 2017 when Gregg Allman died and I interviewed Jaimoe (from Beijing!) and ghost-wrote his thoughts on his longtime partner’s passing. You can read that here. (I never got paid for it, by the way, but it was a labor of love anyhow, even sleep-deprived from the other side of the world.)

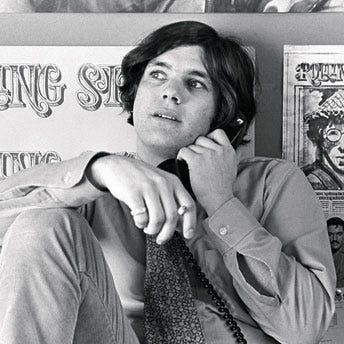

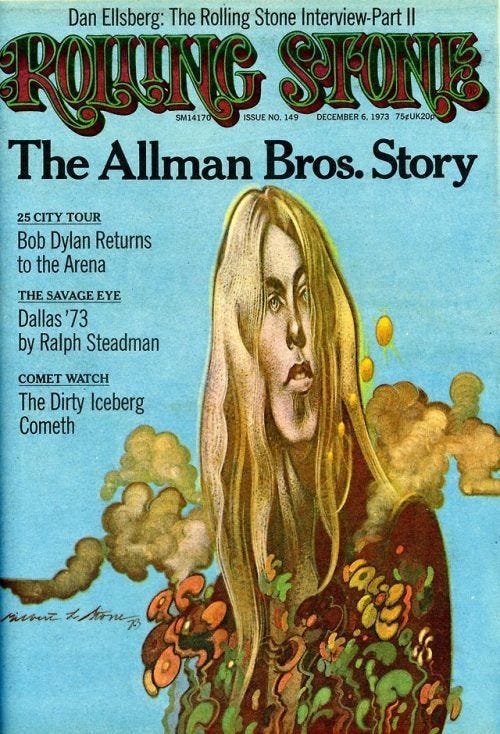

One of the Rolling Stone writers I read and was enthralled with as a kid was Cameron Crowe. I had no idea that he was only a decade older than me, a kid himself when he began. Mostly because of Cameron, and his 1973 cover story on the Allman Brothers Band, Rolling Stone is a character in Brothers and Sisters. I share the excerpt below, because it will help some of you gain more insight into Wenner and Rolling Stone and because it’s fun!

This blog is, as always, free to all. If you enjoy it, please subscribe, and share.

An excerpt from Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s.

The Allman Brothers Band were the hottest, most popular rock act in the country. This presented a problem for Rolling Stone, the country’s most important rock magazine, because the group would not talk to them. They were nursing an understandable grudge over a story by writer Grover Lewis, which not only portrayed the band as bored, drugged out rednecks, but did so in the November 25, 1971 issue that also included Duane’s obituary. Billed on the cover as “Duane Allman’s Final Days on the Road,” the article captured the band at a low point just before Duane and Oakley went to rehab in Buffalo, when they were snorting coke like it was lifeblood.

There’s no reason to doubt the heavy drug use Lewis described or his portrayal of Oakley seeming worn out at age 23, but the writer clearly exaggerated the dialogue. The portrayal of ex-banker Willie Perkins as a kindly hick, some sort of cracker rube, was a red flag to anyone who had ever spoken to the tour manager. Running the piece in the same issue that mourned Duane’s death seemed like a nasty turn of the knife.

“We had some bad experiences with Rolling Stone,” Betts said. “We had invited [Lewis] to travel on the road with us and he really took advantage of it. He just wrote a really bad article.”

Trucks summed up the band’s feelings about the piece in a 2005 letter to The New York Times, in response to a review of a collection of Lewis’ writing: “I am sure that [Lewis] was used to bands falling all over themselves at having one of the great writers from Rolling Stone magazine around. He was somewhat taken aback by our lack of interest in his presence. What he wound up writing under the guise of journalism could have been humorous satire, at best, if it weren't for one very tragic fact: it was published within weeks of Duane Allman's death, and the people at Rolling Stone had time to pull the article but did nothing. …. In Lewis's article, all the dialogue among members of our group seemed to be taken directly from Faulkner. We are from the South. We did and still do have Southern accents. We are not stupid. The people in the article were creations of Grover Lewis. They did not exist in reality.”

If the band felt that strongly in 2005, imagine their attitude in 1973, riding their commercial peak and just two years after the publication of Lewis’ article. They didn’t need any help selling records or tickets and they simply were not going to talk to anyone from Rolling Stone. A long-haired 16-year-old kid in San Diego softened their stance.

Friends of the Brothers are available for private parties and we have an unusual Saturday night opening on November 18, somewhere between NYC and mid Virginia. Drop me a line if you’re interested.

***

Cameron Crowe’s mother did not allow rock and roll records in her house. The college sociology and literature instructor felt so strongly about the music’s lack of redeeming value that she wrote a letter to NBC complaining when she saw Simon and Garfunkel sing “Mrs. Robinson” on The Smothers Brothers TV show. But Crowe’s big sister Cindy hid records under her bed and bequeathed them to him when she left home. Crowe thought he would be a lawyer until he discovered Creem magazine. Then Cindy introduced him to a staff member of the underground newspaper the San Diego Door, which led to him not only writing record reviews, but becoming a protege of Creem editor Lester Bangs, a fellow San Diego native who had been an editor for the Door. Crowe kept writing for a wide range of magazines, including Creem, Crawdaddy!, Circus and Hit Parader.

When he started doing interviews, Crowe was too young to even have a learner’s permit, so he would take the Greyhound bus from San Diego to Los Angeles, where photographer Neal Preston would pick him up at the Greyhound station and drive him to wherever they had an assignment together. Their destination was often the Hyatt House on Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood, lovingly referred to as the Riot House, and the scene of much rock and roll mayhem. Crowe had skipped kindergarten and two grades in elementary school, and was used to being the youngest guy in the room.

The young writer developed a good relationship with Capricorn Records Vice President of Publicity Mike Hyland, who arranged phone interviews for him with the Marshall Tucker Band, Wet Willie and Cowboy. “He knew I was a big fan of the Allman Brothers Band, and I’d kinda dreamt aloud that I’d one day like to write about them,” Crowe says. Hyland arranged a phone interview with Betts for Rock magazine, which went well. The next step was a short backstage interview, on the condition that he only speak about the North American Indian Foundation and the guitarist’s involvement with Native causes. When they spoke, the writer made sure to refer to Betts only as Richard, his then-preferred name, and as the guitarist got comfortable, he began discussing how hard it had been to carry on the band after Duane’s death.

“Holy shit!” Crowe thought, well aware that neither Betts nor Gregg had discussed this topic in detail. He immediately called Rolling Stone editor Ben Fong-Torres, who told Crowe that if he could get more material, the magazine would be interested in a major feature, maybe even a cover story. The only problem now was to convince the Allman Brothers Band to allow any journalist - much less one representing Rolling Stone - to go on the road with them again. Crowe’s earnestness and youth worked to his advantage, as did good words from Hyland and, most importantly, from Betts himself.

“I took to Cameron Crowe,” Betts told. Wade Tatangelo of the Sarasota Herald Tribune. “I liked him. He was a young kid trying to make a big break for himself. The band was really gun shy about having anyone come on the road with us… [but] I said, ‘This is a good guy. I had real good luck with him. He did a nice article.’ I was vouching for him and finally talked the guys into letting him come out with us.”

Betts’ instincts were spot-on. Crowe was in the process of becoming one of the best rock journalists of his era. His stories focused on the music and how it was created; he cared more about the rock and roll than he did the sex and drugs. “I always felt like as a journalist, I got a seat in the front row, and I wanted to serve all the people like me that wanted to be in the front row,” Crowe says. “I wanted to be a fly on the wall and bring that experience back to the fans and followers of the bands I was writing about.”

The editors of Rolling Stone also saw the advantage of using the earnest youngster to mend fences with bands they had insulted and enraged in various ways. The Allman Brothers Band weren’t the only group who fell into this category. The magazine had also disparaged and angered Led Zeppelin, the Eagles and Deep Purple. Crowe profiled all of them, as the older editors handed the decade’s most important bands and their stories to the kid.

‘I was aware of that situation and I wore it like a badge of honor,” Crowe says. “I was somebody who loved those bands and would have bought the magazine looking for the type of article I wanted to write. I felt like I was performing a service for fans like me. To me, those bands were as deserving and passionate as the acts that had gotten such great play in Rolling Stone. I wanted to put my guys on the team. And the Allman Brothers took the biggest risk in trusting me.”

Excerpted from Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, copyright 2023, Alan Paul.

In the same spirit, I thank Cameron for taking the risk in trusting me to tell his story. The above excerpted section is the start of an extensive chapter of his experiences on the road with the Allman Brothers Band, and how it formed the backbone of Almost Famous. Buy Brothers and Sisters now.

Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, was my third straight instant New York Times bestseller, following Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. My first book was Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about my experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band. It was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. I am also a guitarist and singer who fronts two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band. We may well be playing near you soon. Click here to find out.

Gary Trudeau had Wnner's number in the early 70's and made fun of him in Doonesbury (Duke once said he needed both hands for social climbing). He is the very epitome of establishment but he pretends to be cooler than cool. His prejudices against certain great rock acts are bizarre. Maybe now that he is gone Jethro Tull will get nominated.

Thanks for turning something negative -- Wenner's well-deserved roasting for being a cringe-y Boomer disappointment -- into something positive: a timely reminder that, Wenner's founder status and outsized influence notwithstanding, he is not the all of Rolling Stone, and the magazine was frequently better than his narrow vision.

Thank goodness for Cameron Crowe's work, and also Ellen Willis' (R.I.P.).