Happy 80th birthday Jaimoe! An appreciation and interview with Allman Brothers Band employee number one.

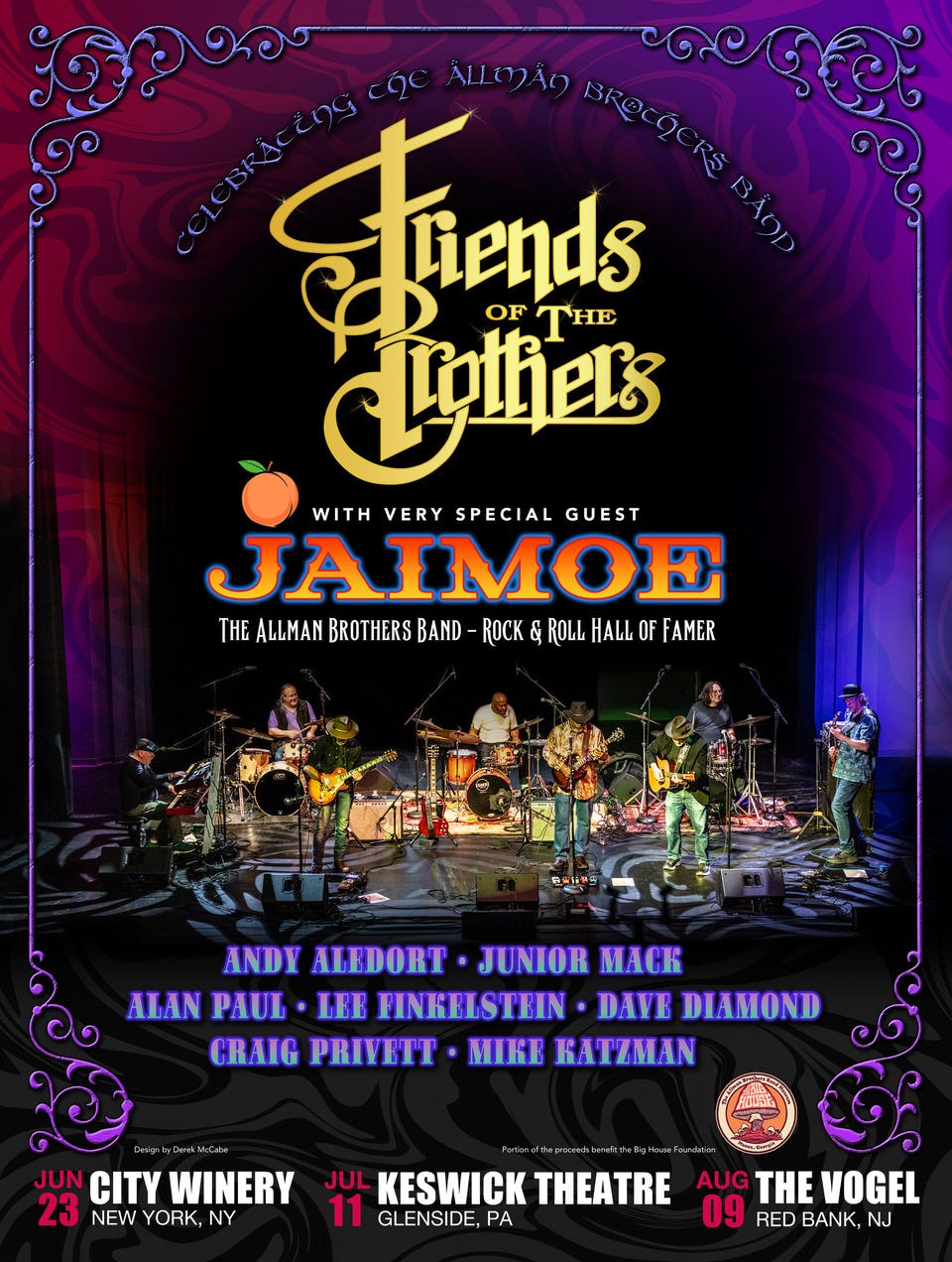

Celebrating the last surviving original member of the ABB as my band Friends of the Brothers prepares to play three more shows with him.

HAPPY 80TH BIRTHDAY JAIMOE!

So very honored that I am playing shows with you. Two down, three to go, for now.

-July 11, The Keswick Theatre, Glenside, PA

-> https://bit.ly/4bxGAuC

-July 24 Ridgefield Playhouse. Ridgefield, CT JAIMOE'S 80th birthday party

-> https://bit.ly/4clsNb2

-August 9, The Vogel, Count Basie Center for the Arts, Red Bank, NJ

- > https://bit.ly/4bQL6EG

Jaimoe was the Allman Brothers Band member I knew least before I started writing One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. We had met backstage quite a few times over the years, most memorably when he saw me in the basement of the Beacon with my three-year-old son Jacob and came over to play with him. He didn’t know who I was; he just saw a dad with a young kid and came over to chat. Another memorable backstage meeting was when he thought I was Vince Vaughan. And there was my interview with him in 2001 for a 30th anniversary of At Fillmore East story. I asked him if it was a typical night or a particularly great performance and he answered simply and accurately, “Both.”

I interviewed Jaimoe for hours while writing One Way Out and found him consistently delightful and enlightening. Some interviews took place over multiple conversations, with him calling back four days later and resuming in mid-thought. it took me a while to get used to these types of things, but getting to really know Jaimoe and become his friend has without a doubt been the great, most satisfying and life-changing part of my whole experience as Allman Brothers biographer.

Traveling to gigs and festivals with him, I’ve observed countless moments of grace, kindness and generosity: him taking a long time to discuss a fan’s favorite Allman Brothers show at length; hobbling on a bad knee after a hotel breakfast buffet server to give her a tip; and slipping money to a young drummer at a music festival with a vintage kit in need of repair. He’s equally well known for his passion for making strange food and drink combinations, introducing me to the delights of coffee tea and vodka wine. They’re exactly what they sound like. Passing an icy red Solo cup of vodka wine with Jaimoe in a pitch dark hospitality tent at midnight at the Peach Festival is an indelible memory. And then there’s the sage-like wisdom he drops all the time. I’ve called him for a yes/no fact check and ended up in hour-long history or philosophy lessons.

“One thing I’ve learned in life is hindsight ain’t 20/20,” he told me once. “It’s not gonna be that you don’t know what you need to do in life, and if you’re blind to that, then you’ve got a problem.”

A native of Gulfport, Mississippi, Jaimoe, was born Johnie Lee Johnson and known as Jai Johnny when he toured with soul singers like Otis Redding, Joe Tex and Percy Sledge, before saxophonist Juicy Carter named him Jaimoe and it stuck. Despite his success on the soul circuit, Jaimoe’s true love was jazz and by 1969, he had made up his mind to pursue his passion. “I was going to New York and try to be a jazz musician,” he says. “I figured if I’m going to starve playing music, it might as well be the music I love.”

Jaimoe’s jazz odyssey was delayed when he got word that there was a hot guitarist named Skydog making a name in Muscle Shoals, Alabama working with the likes of Wilson Pickett and Aretha Franklin. Allman had a management contract with Phil Walden, who had managed the late Redding and he heard Johnson’s playing on a songwriting demo and wanted to meet him. Jaimoe moved into Allman’s cabin on the banks of the Tennessee River and the two started getting to know each other personally and musically, talking and playing constantly, before they headed to Jacksonville, Florida and put together the rest of the group: guitarist Dickey Betts, bassist Berry Oakley and fellow drummer Butch Trucks.

“Duane dropped me off at Butch’s house with my drums, introduced me and drove away,” Jaimoe recalls. “We took them in, set them up and just started playing – and it worked. People always ask how we worked it out, but we just listened and played. Both of us learned to play in marching bands with a lot more than two drummers. He was a great drummer. Almost everything I’ve ever played in my life that someone said was great was a reaction to something Butch played.”

“Music is music and there’s no such things as jazz or rock and roll,” he says. “I wanted to be the world’s greatest jazz drummer and I didn’t want to play rock and roll or funk, which I thought was too easy and then I got a chance to do it and I couldn’t play what needed to be played. I had to learn and music was everything.”

Jaimoe describes the early years of the Allman Brothers Band as “just the greatest thing in the world,” with like-minded musicians learning from each other, feeding off each other and constantly spurring one another to new ideas and new heights, rising beyond what any of them could have imagined on their own.

“It was like having your masters and you’re working on your doctorate - and you’re doing it with Einstein,” he says. “We were just playing music and it was going great, so we didn’t think about what would happen in a month. I think Duane did. He always had a vision, but I had no other thoughts except how great the music we were playing was. The whole world closed out.”

As an African American in an otherwise white hippie band in the deep south in 1969, things weren’t always easy for Jaimoe, but he doesn’t particularly like to talk about that side of things, brushing it off repeatedly. But he was incredibly proud in 2017, when he received the prestigious Harriet Tubman Medal of Freedom from the Tubman Museum in Macon. “I was knocked out,” he said. “I thought it was a joke.”

When I asked him if civil rights activism played a role in his music, he paused, before responding. “I really don’t know,” he said. “It comes from a different place, but I’ve always felt good about the freedom of music.”

Enjoy this interview with Jaimoe about why he got off the couch to play with us and so much more.

WHY DID YOU DECIDE TO START PLAYING OUT AGAIN?

It’s what I’ve been doing since I was 16 and, shit, I’ve had 10 surgeries, including two knee replacements and a shoulder replacement just so I could play. If I can play, I have to play! I started playing a lot to CD’s and tapes and stuff and didn’t really have the desire to do other than that, but then little stuff started popping up. Certain things would trigger me playing a different kind of way - especially playing with that first Sea Level record and some Ernie K-doe and other New Orleans records. Some music inspires me and some does nothing and leaves me thinking I might as well go watch a movie.

The thing about a CD is when you learn how to play with it and you can change it, versus playing along with what the drummer is playing versus eliminating the drummer in tour mind. I told [Miles Davis drummer] Jimmy Cobb, “Man, I tried to change your history” because I used to play with Miles Live at the Blackhawk and stuff. Jimmy is swinging his ass off, but I get inspired to try new things. When you start mastering the fact of taking a piece of music and changing it and making it work without fucking up the whole thing, then you’re going in the right direction. But…

…EVENTUALLY YOU HAVE TO PLAY WITH OTHER PEOPLE?

Yeah. When you can master those CDs and play them in your mind and erase what the drummer is doing and play along as if it was a minus one, then you realize ok, the CDs are not gonna change. They’re gonna play the same thing over and over. Only playing with musicians do things change one way or the other and that’s what music is.

WE ARE SO HONORED AND HAVING SO MUCH FUN - BUT WHY DID YOU CHOOSE FRIENDS OF THE BROTHERS?

Because I heard y’all playing at Peach [last year] and you motherfuckers were cooking. There were only three or four bands playing with that kind of energy at the whole festival. All the rest of them, including some big names, they weren’t playing like that.

TICKETS TO ALL SHOWS: WWW.FRIENDSOFTHEBROTHERSBAND.COM

YOU’VE PLAYED WITH JUNIOR MACK FOR A LONG TIME. WHAT MAKES HIM A SPECIAL TALENT?

Junior doesn’t play like Duane or Derek. He’ll play their music, of course, but he’s coming from his own place, and a lot of it was gospel and spiritual. Junior is a huge talent and he knows a lot of music: blues, progressive jazz, gospel. He brings all that stuff to the Allman Brothers songs and that’s how it should be.

YOU CAME UP AS A R&B AND SOUL DRUMMER, THEN MADE THE JUMP INTO THE WORLD OF ROCK 'N' ROLL WITH THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND IN 1969. HOW DID YOUR FORMATIVE YEARS OF DRUMMING PREPARE YOU FOR PLAYING IN THE ALLMAN BROTHERS?

You can go from the Otis Redding and blues to rock, no problem. It’s all raw, open notes. I wanted to be a jazz player only knowing what I heard on records. I was schooled in music and drumming by a great music teacher and high school marching band and I learned how to play; what you do with it doesn’t matter. All this music came out of the same place: churches. Last night on The Voice a guy did [Otis Redding’s] “Try a Little Tenderness” and I told my wife, “You hear that horn? It’s straight from the church.” It’s traditional spiritual music.

Blues this and rock that, whatever someone stuck a name on, it’s coming from the same place and you go up the ladder to try and become what you want to be. I once heard BB King say that the only difference between blues and gospel was the words. My spiritual godfather Antonio DaSilva, a shaman voodoo priest, told me the same thing when I asked him how I know what to play: “The only difference in the music is the words. Don’t say the words.”

WHAT WAS IT LIKE IN THE INITIAL STAGES OF THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND, ESPECIALLY GEARING TOWARDS THE BAND’S FIRST, SELF-TITLED RELEASE IN 1969?

For me, it was like everything I ever wanted to play. I discovered that the first time I ever played with Duane in Muscle Shoals. Duane got done with a session and rolled that Fender Twin amp out of the main room next door where I had my drums set up and we just started playing. Then he called Berry [Oakley] to come and once he joined in, I was in heaven. And it wasn’t like something I learned over time or had to think about it. It was immediate: this is the shit I’ve wanted to play all my life.

BUT YOU HAD NEVER KNOWN IT!

Yeah. Or maybe I did. Once you hear what you’re searching for, you immediately know what it is. It’s not like something that’s foreign to you. You knew it all your life. Everything had been building to that and when you find it, you know it.

Berry was a real blues guy. Duane and I were just two adventurous cats and we just played, and what was so interesting to me is we scared the shit out of the cats in that studio, man. They just had never heard it approached like that. They were used to “play so many bars of this and so many bars of that.” We just played, no talking. These were natural things like breathing. When you started playing with someone like that you knew what to play. It was all right there. So the only development from there to the Allman Brothers Band and our first album was the development of the ideas of six people playing in together a style that as Duane said, moved it forward. We just had the right chemistry with the right people and it was like breathing.

IN THE 1990S, THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND CAME BACK AND GAINED A NEW, YOUNGER AUDIENCE. DO YOU FEEL THAT THAT TIME AND THE JAM BAND WORLD YOU GUYS WERE LEADING HELPED BRING A NEW DIMENSION TO YOUR SOUND, AND ULTIMATELY SHAPE YOUR LEGACY?

Yes and no. It was just another step because you take what you heard all your life and hear it being approached differently because there are people who came from another place. So guys like Warren [Haynes], Derek [Trucks] and Oteil [Burbridge], shit they knew the Allman Brothers but they had different experiences than us. They had played with different people, listened to different music and had different ideas. And everything affects everything, so I took a different approach and we all did, I guess.

I was just relating to what I was hearing, which is all you can do. When you really understand music, it’s like the wind. It goes this way, it goes that way. You have your base and it’s never going to move from 1969 to 1995 to 3005. It’s like “Thou shalt not steal.” People in 3005 might not know the 10 commandments, but there’s never gonna be a time when motherfuckers should steal. Things advance, but the rules don’t change.

YOU ARE THE LAST ORIGINAL MEMBER OF THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND. DO YOU FEEL AS THOUGH YOU NOW HAVE THIS GREAT RESPONSIBILITY TO CARRY ON THE MUSIC OF THE BAND?

I felt that way when the band existed and even more so now. I believed that the legacy was a serious thing way before Butch or Gregory passed and even Duane or Berry! I said, “We are now the people that we looked up to.” That means that when you go on stage, you better be jamming and playing your ass off. We are the masters that we looked up to and when you hit the stage you cannot be out there shucking. Whatever you do, do it as a master.

As soon as I started playing with Duane, we set out to be great and it’s something to live up to, but it’s not hard. It’s what you do. I picked up a drumstick inspired by Gene Krupa, Elvin Jones and Max Roach and I’ve been trying to play great since the first time I played along with their records. Other people have done that playing to Duane or whoever what else. That’s an honor!

My fourth book, Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, was published July 25, 2023, by St. Martin’s Press. It was the third consecutive one to debut in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List, following Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. My first book, Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about my experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band, was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. I am also a guitarist and singer with two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

love this. just shouted y’all out on my own bday post here on substack

Fantastic interview and when he said "Because I heard y’all playing at Peach [last year] and you motherfuckers were cooking." he was speaking the truth!!! Man you need to bring that act to Pittsburgh!!!