Brothers Of The Road: The Powerful Bond Between The Allman Brothers And The Grateful Dead

Digging into the two bands' deep friendship on the anniversary of an epic collaboration at the Fillmore East. A Brothers and Sisters excerpt.

My book Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band And The Album That Defined The 70s does a deep dive into the relationship between the Allman Brothers and the Grateful Dead. I believe that it is the most extensive exploration of this ever done. Their collaborations peaked in 1973, with two summer shows at Washington DC’s RFK Stadium and, of course, the Watkins Glen Summer Jam. The excerpt below, however, focuses on their first official double bill, February 11-14, 1970 at New York’s Fillmore East, a match made by promoter Bill Graham, who deeply loved both bands.

Enjoy. If you haven’t bought the book, please consider doing so! And to suppoer this free blog, please subscribe and share!

Excerpted from Brothers and Sisters:

The Grateful Dead was another Bill Graham favorite, and the two bands’ first official shows together were a run of three at the Fillmore East, February 11, 13 and 14, 1970. The Allman Brothers opened. Love played the middle set.

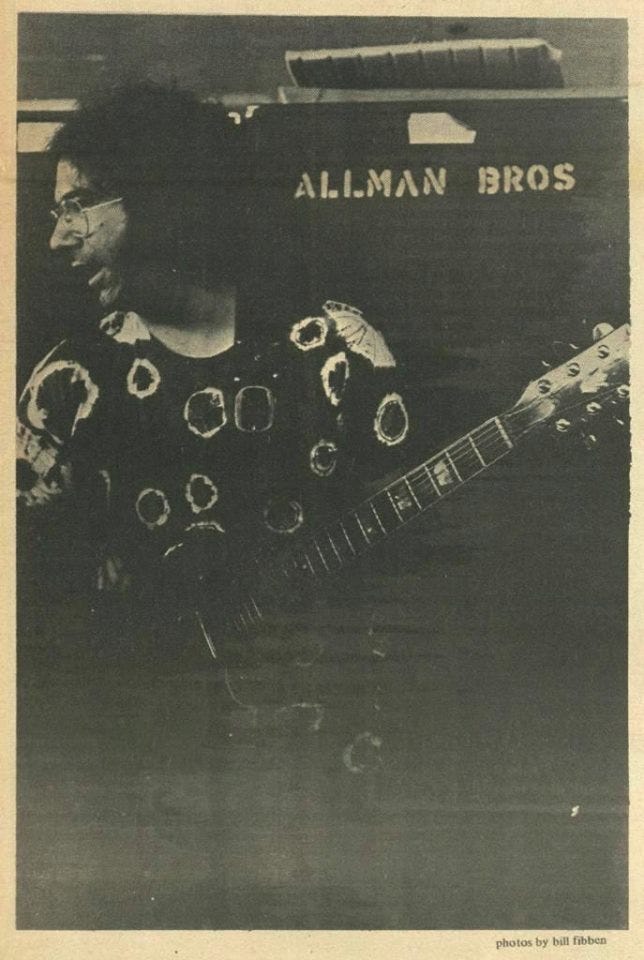

Dead soundman (and legendary LSD chemist) Owsley “Bear” Stanley was already a fan of the Allman Brothers Band so he taped their sets. On the way to the first show, Garcia hipped bassist Phil Lesh to the opening act. “Hey, Phil, make sure you check these guys out,” he said. “They’re kinda like us: two drummers, two guitars, bass and organ, and I hear they jam hard.”

No one was more excited or understood the pairing’s sympatico nature better than Graham, who booked virtually every contemporary band of note at his venues and favored these two. “When the Dead and the Allman Brothers played the Fillmore East, it was rock at its very best,” he said.[iii] “They both had something undeniable that you can’t buy: the ability to excel and just completely captivate a crowd with no production of any sort. It was all in the greatness and intensity of the music and the focus and intent. They exemplified communal pleasure, where everyone had the same idea. And it didn’t matter what they played. It was like going to your sister’s house; whatever she serves is going to be good because you’re so comfortable. I loved to take someone who thought they didn’t like either of those bands and set them up on the side of the stage. A half hour later they were transported.”

In between the first and second shows on February 11, the Dead met Gregg, Duane, Butch, and Jaimoe backstage. Fleetwood Mac also were in town to play Madison Square Garden on February 13 in support of Sly and the Family Stone on a bill that included Grand Funk Railroad and Richard Pryor. The Dead and Fleetwood Mac had played the Warehouse in New Orleans together less than two weeks earlier, and after the first night, January 30, the Dead were famously “busted down on Bourbon Street.” The February 1 performance became a drug-bust fundraiser, with Peter Green sitting in that night on “Turn on Your Lovelight.”

Lesh was pleasantly surprised when he heard the Allman Brothers play “Mountain Jam” during a blistering set that kicked off the midnight show.[i] The extended instrumental, which took different flight paths every time the group performed it, is based on the melody of the English folk singer Donovan’s “There Is a Mountain.” The Dead had been playing around with the simple, catchy lick for years, with Garcia regularly quoting it in “Alligator.” Lesh thought it was hip that the Allmans had crafted an entire monumental jam song from the same few notes. “It was quite an eye opener,” Lesh said. “It was really cool. The Allman Brothers were doing it their own way, but there was obviously a common denominator. It was a shock of recognition that the Allman Brothers Band was out there performing that same line of inquiry into the art of music.”

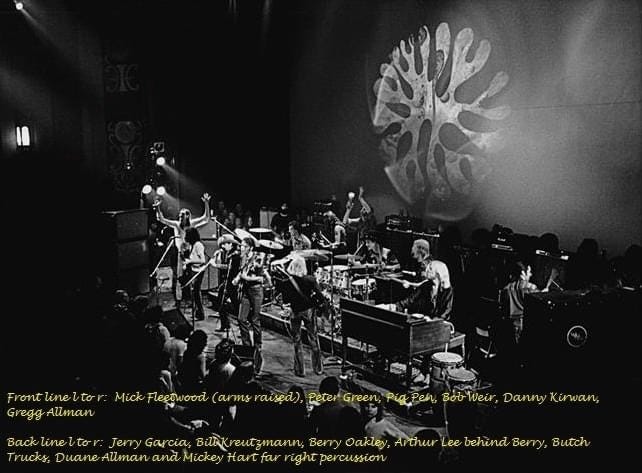

The first and arguably greatest jam between the two bands occurred at the end of the Dead’s late show, in the wee hours of the morning of February 12. During the quiet section of “Dark Star,” Lesh was startled by the clarion sound of Duane’s slide guitar. Garcia had not told him about any planned sit-ins. As Allman was finding his footing, Peter Green also plugged in, and he and Duane took off as the song turned the corner towards its minor-key segment. The rhythm section, now including Garcia and Weir, locked into a groove, and the song took flight before shifting into the four-bar pattern the band dubbed “Spanish Jam” because they took the riff from the Miles Davis / Gil Evans album Sketches of Spain.

Garcia and Allman were trading licks when Gregg appeared on the organ bench, adding some sustained notes followed by quick licks. By the time Gregg and Duane were playing call and response, Trucks had also joined on drums and Mickey Hart was literally banging his gong. As Green brought the song to a climax, Lesh and Weir launched into the familiar riff of Bobby Bland’s “Turn on Your Lovelight,” which had been not only a highlight of Dead shows for years but also a frequent cover in Gregg and Duane’s previous bands like the Escorts[CE1] , the Allman Joys, and Hour Glass. The Dead had steered the music right into Gregg’s sweet spot, and he sounded suitably juiced.

By that time, Fleetwood Mac drummer Mick Fleetwood and guitarist Danny Kirwan were also on stage, though Fleetwood was heavily tripping and did not play, roaming the stage with a grin plastered across his face. “I had a tom-tom and a snare drum and I was gooning around on the stage,” Fleetwood recalled. Bill Graham also emerged, tripping hard, smiling and hitting a cowbell.

Pigpen, who walked off for “Dark Star,” returned to sing atop a band that now included five guitarists and four drummers. He sang two verses, then Gregg took the third, finishing with a guttural howl that cut deep, before he and Pigpen traded vocals. Halfway through the song, Oakley took over on bass, because Lesh “just want(ed) to listen for a while,” he wrote. As the band segued in and out of Howlin’ Wolf and Hubert Sumlin’s “Smokestack Lightning” riff, Lesh distinctly remembers the sound of “everyone flat out wailing.”

The bassist felt his mind stretching out of shape as the mega band drove the song to a frenzied climax, Jerry Garcia, Duane Allman, and Peter Green egging each other on. When the song finally came to its wild conclusion, Weir took the mic and energetically proclaimed, “From all of us to you, thanks and good night.”

But the crowd had not had enough and kept cheering, as a dazed Fleetwood, who would later describe this as a “crazed night,” sat on the lip of the stage, microphone in hand, repeating: “The Grateful Dead are fucking great!”[v] Garcia, Lesh, and Weir came out to wrap things up with a single acoustic guitar. The bassist said, “If you folks would all be kind enough to be quiet for a while, we’re gonna sing a purty little old song with only an acoustic guitar.” They played “Uncle John’s Band,” and the night was finally over.

After the dazed crowd filled out, someone opened the door behind the stage, and the musicians looked out at the New York City streets bathed in golden early-morning light, snow gently falling.[vii] Lesh, Weir, and Garcia embraced in a group hug, and one thought ran through the bassist’s head: “This is what it’s all about.”

Joe Rosenberg was a twenty-year-old college student at the midnight show, seeing all three bands for the first time. He was mesmerized by the Allman Brothers’ performance from the first note of the show-opening “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” but he dozed off during the Dead’s wee-hour performance, waking up in the middle of the amazing “Dark Star” jam with Duane and Jerry wailing and Fleetwood dancing around the stage. It was a mystical, magical experience, like a [CE3] euphoric dream. Stumbling out in the morning, [CE4] he found himself walking behind two members of Love and eavesdropped on their conversation. “They were talking about how incredible the jam was and how remarkable the Allman Brothers had been,” Rosenberg recalled.

Also there was Bruce Kaufer, a sixteen-year-old high school senior in town on a school trip to see a Broadway play. He had been at Woodstock, where he saw the Dead, but it was this night at the Fillmore East that made a huge impression; it changed his life, he said. “Those shows lit the fire inside to pursue live music in all its shapes and genres,” said Kaufer. “Ending up at the Fillmore that night was a simple twist of fate.”

The next day, Duane sat down for an interview at Crawdaddy magazine’s New York office, still glowing from the jam. “Peter Green, Garcia, Bob Weir—so beautiful, what it’s all about,” he said. “Just getting down to that good note, man. Just grooving and looking along on that one good note.”

The members of the Dead were similarly enthusiastic. Owsley described the Allman Brothers performances as “fantastic” and “a real inspiration for the boys.”[ix] After a night off, the Dead played two more shows on this run, February 13 and 14, turning in some of their most memorable performances of the Pigpen era. They were good enough to be released twice, in 1973 as History of the Grateful Dead, Volume One (Bear’s Choice) and in 1996 as Dick’s Picks, Volume Four. [1]A couple of months later, on May 10, 1970, the Dead played the Sports Arena in Atlanta, with Bruce Hampton’s Hampton Grease Band opening.[2] When the Dead’s gear didn’t make it, the Allman Brothers sprang into action and drove their stuff up from Macon.

“The Dead arrived in Atlanta without their equipment, and I called Duane at home in Macon early on Sunday morning to ask him if I could rent his sound system,” recalled the show’s promoter, Murray Silver.[x] “He asked me who it was for, and when I told him, he [said] that I could have it for free. The Brothers brought their equipment to Atlanta.”

“I had to borrow a bass; I didn’t even have my instrument,” Lesh said. “Talk about thumb up your ass!”

Oakley, Trucks, Gregg, and Duane watched the show from the stage and sat in for a show-closing jam on “Mountain Jam” > “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” Silver describes that jam as “unlike anything that has been heard before or since.” The Great Speckled Bird, the main chronicler of Atlanta’s underground scene, agreed, calling the show “one of the great musical/sensual experiences the Atlanta hip community has ever had.”[xii] Unfortunately, there is no known recording of this show. [CE5]

Making their sound system available for free was emblematic of Duane and the Allman Brothers’ esteem for their San Francisco friends. “I love the Dead!” Duane said in a 1970 on-air interview with New York DJ Dave Herman.”[xiii] He added that “Jerry Garcia could walk on water. He could do anything any man could ever do. He’s a prince.”

Excerpted from Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band And The Album That Defined The 70s, Copyright 2024, Alan Paul.

[1] Grateful Dead Records released a compilation disc of Owsley’s recordings of the Allman Brothers in 1997, and a more extensive three-disc version was released by the Owsley Stanley Foundation in 2021.

[2]Duane loved the Hampton Grease Band and helped them get a deal with Capricorn. Decades later, Hampton, now calling himself Col. Bruce Hampton, became first an Atlanta fixture and then a major inspiration to a new generation of jam band musicians. Future Allman Brothers band members Oteil Burbridge and Jimmy Herring started in Hampton’s Aquarium Rescue Unit.

This blog remains free for one and all and it is a word of mouth operation, so if you enjoy, please subscribe and share.

My fourth book, Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, was published July 25, 2023, by St. Martin’s Press. It was the third consecutive one to debut in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List, following Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. My first book, Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about my experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band, was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. I am also a guitarist and singer with two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

Thanks @Shane Tobin... at a quick glance, list looks great. I already did one!

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/7mQlBu9jnicajkmfztpHsd?si=6ece5e59d1c54cf3

Just got finished with your book. Actually I read the first half and then listened to the second half. Loved hearing the interviews with the band. You did an excellent job covering this transitional period for the Brothers. I made a playlist to go along with the book so I could listen along as you covered the various musical moments. Let me know if I'm missing anything on here: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/407brr3PZhvhwccMJr4fGk?si=82f07436628c4722