Brothers of the Road: More on the relationship between the Allman Brothers Band and the Grateful Dead

On the anniversary week of two epic sit-ins, 7/16-17/72 in Hartford and the Bronx, a dive into the ties between the two greatest American bands of all time.

My book Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s is about a lot more than the album of the same name and includes the most extensive reporting ever about the relationship between the Grateful Dead and the ABB. On the anniversary week of two epic sit-ins, I present an excerpt from Brothers and Sisters.

"I love the Dead!” Duane Allman said in a 1970 on-air interview with New York DJ Dave Herman. “Jerry Garcia could walk on water. He could do anything any man could ever do. He's a prince."

At least once, on July 10, 1970, at SUNY Stonybrook, Duane clearly quoted “Dark Star” during “Mountain Jam.” Lesh says that Garcia returned Duane’s appreciation and respect and that the two had an obvious bond and similarities.

“Duane and Jerry just knew what to do, as musicians on that level do - when to play, when not to play,” Phil Lesh says. “Jerry had an immense amount of respect for Duane. Duane truly was a master. His spirit, his fluency… listening to Duane play was like watching a flower grow. We all felt that way about his playing. Beauty is truth, truth is beauty.”

Duane and Jerry had a budding friendship that had begun with mutual respect and was growing into something more. On November 21, 1970, Duane popped into the studios of WBCN in Boston as Bob Weir and Garcia performed.

Recalls Charles Laquidara, of WBCN, “I was working the 10-2 shift and the person answering our listener line said, ‘There are a bunch of musicians at the door saying they played two different clubs and want to come up and hang.’ It was Bob Weir, Jerry Garcia, Gregg and Duane Allman and Pigpen....and Duane didn't take his guitar! It was a great, laid back evening! “

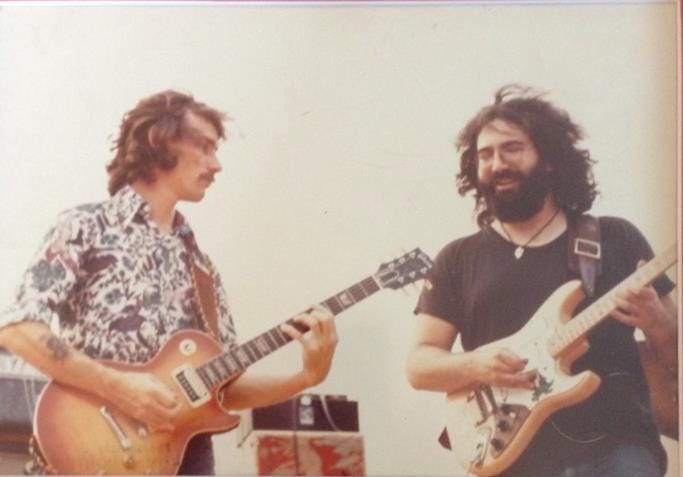

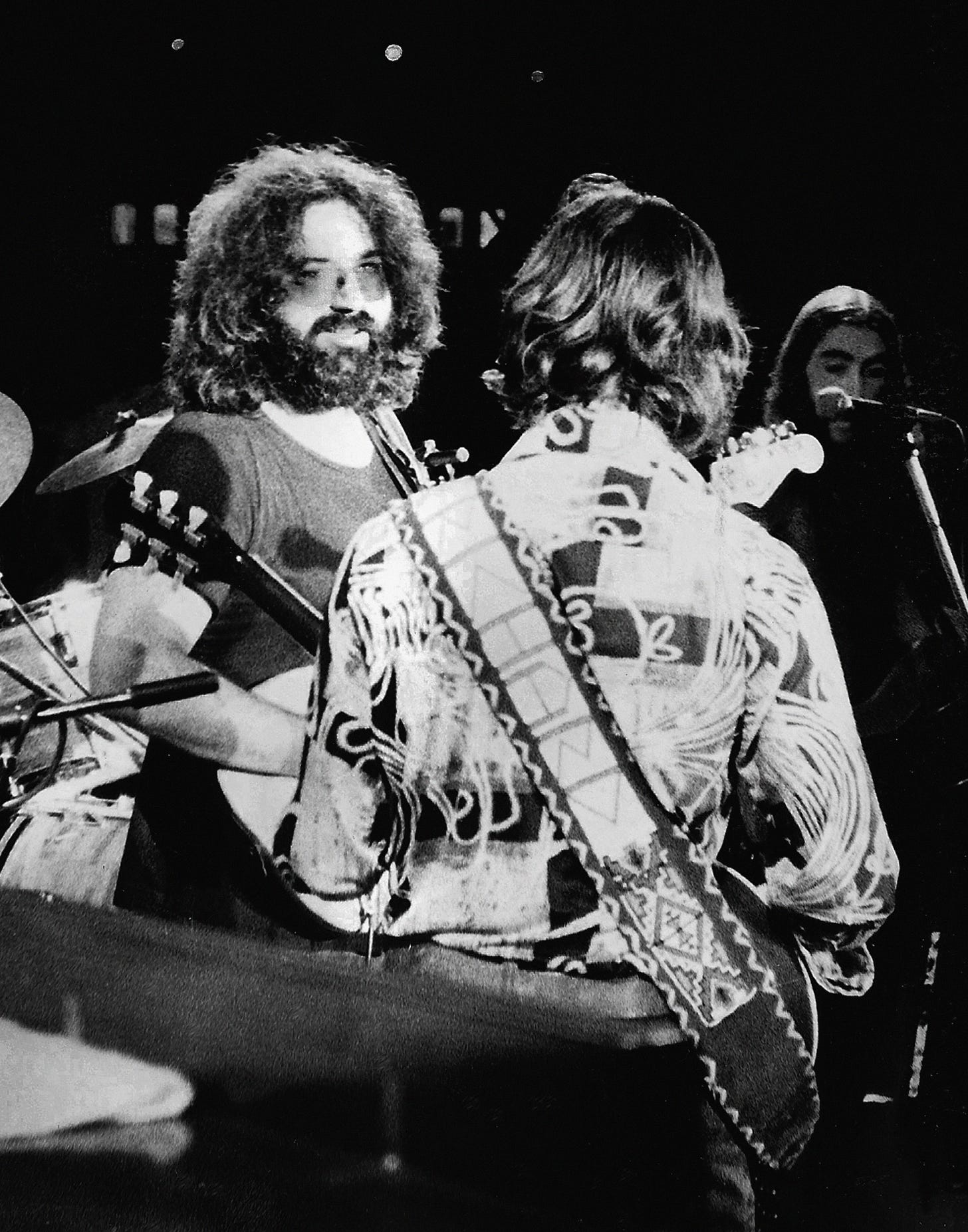

With Duane guitar-less, Jerry passed him his acoustic, but the two did not play together.Duane turned up on stage in New York on April 26, 1971, during the Dead’s final week of shows at the Fillmore East. He joined the band for three tunes: “Sugar Magnolia,” “It Hurts Me Too” and “Beat It On Down The Line.” It was a month after the Allman Brothers Band had recorded the shows that became At Fillmore East, their breakthrough album. Duane’s slide dominates Elmore James’ “It Hurts Me Too,” while he and Garcia take flight together on the other two songs, playing with graceful ferocity. It would have been impossible for anyone to believe it would be their last time on stage together. The burgeoning friendship was just one more victim of Duane’s death on October 29, 1971.

“We developed a close relationship with Duane that unfortunately never had the time to blossom because he was gone so soon,” says Weir.

Still, the relationship between the two bands was just getting started. When the Dead played Hartford’s Dillon Stadium on July 16, 1972, Betts, Oakley and Jaimoe drove up from New York on an off day, with Jaimoe’s kit in the back of the limousine. They watched the show from the side stage, then joined in to play “Not Fade Away” > “Going Down the Road Feeling Bad” > “Hey Bo Diddley” and an encore of Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.” Oakley replaced Lesh on bass, and Garcia and Betts riffed off each other with glee, while Jaimoe and Kreutzmann locked into one another with ease.

“There’s only ever been three drummers I enjoyed playing with: Butch Trucks, Bill Kreutzmann and Buddy Miles,” says Jaimoe. “Because they listen and if you do that, it really don’t matter if there are 13 guitars, 15 basses, 20 sets of drums, whatever else. I always loved playing with Bill.”

This was Betts’s first time sitting in with the Dead; he had previously left that to Duane.

The next night, Weir, Garcia and Kreutzmann returned the favor, showing up at the Allman Brothers Band’s show at Bronx’s Gaelic Park, and playing an aggressive “Mountain Jam” to close the show. Betts and Garcia’s joy at playing together was readily apparent.

Though Gregg spoke disparagingly about the Dead in his later years, there was no animosity on his part during this time. In 1974, when Melody Maker interviewer Chris Charlesworth mentioned that the Brothers and the Dead had some similarities, Gregg readily agreed. “He loved the Dead, and respected Garcia a lot,” Charlesworth wrote.

In 1972, the two bands were planning shows together in the wake of Duane’s death. They were scheduled to jointly play Houston on November 18 and 19. Dead crew member Steve Parish describes these shows as “trying to support our friends” during a difficult transition. Unfortunately, things were about to get more difficult when Oakley was killed in another motorcycle accident on November 11, 1972. They canceled the two nights in Houston, which included two hours of “open jam” at the end of each night. The Dead played that show alone. The Allman Brothers also pulled out of their scheduled slot opening three shows for the Dead at Winterland December 10-12, 1972.

Even with Duane Allman and Oakley shockingly gone, the groups’ mutual admiration was unchecked and lines of communication remained open. “We wanted to work together even more after the shows were canceled because of Berry’s death,” says Bunky Odom. “We kept talking and talking.”

When the Allman Brothers resumed touring with their regular vigor in 1973, they scheduled some very large shows with their California brothers. “Playing shows together was just an obvious and natural desire,” says Sam Cutler, then a Grateful Dead manager. “We realized that if we added our energies together, it was like one plus one makes three. It would be mutually beneficial to both bands.”

The first show was Bill Graham’s inaugural Day on the Green, May 27, 1973 at California’s Ontario Motor Speedway. Advance tickets sold for $7.50. A crowd of 150,000 was expected. The Pomona Progress Bulletin reported on May 8, “The Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers, and Waylon Jennings will take part in the first rock concert at the Ontario Motor Speedway… Law enforcement officers will set up road checks within a five-mile radius of the stadium to be sure that only cars with special stickers and people with tickets are allowed in the area.”

Two weeks later, the concert was canceled. Local police and civic officials demanded the show end three hours before sundown, which would have meant wrapping up at about 5 PM, making the timing simply too tight.

The groups found more accommodating municipalities on the East Coast, with three giant shows - two at Washington DC ‘s RFK Stadium followed six weeks later by the Summer Jam at Watkins Glen, featuring both groups and The Band.

“The Dead were as big as the Beatles in the Northeast - say from D.C. on up,” says Odom. “I’m not exaggerating. The Allman Brothers Band were just beginning to get big up there - they were huge in New York City, and it was starting to spread, but the Dead was already huge in the entire region. … They helped the Allman Brothers develop in a very hip section of the country that we didn’t completely understand in the South.”

Cutler similarly saw the Dead’s collaboration with the Allman Brothers as an opportunity to expand their reach, as well as proof that it was possible to be as popular in the rest of the country as they were around their California home base and their Northeastern stronghold.

“The Allman Brothers were sort of the Southern version of what the Grateful Dead was in California,” says Cutler. “I was trying to take the band to a much larger space, to the national fan base we knew was out there. We knew that the alternative society was everywhere, not just in California. The Allman Brothers were proof of that. They represented the Southern tribe of freaks.”

As the managers looked at tapping one another’s fan bases to expand their popularity into different regions of the country, the musicians simply enjoyed one another’s company and any opportunity to interact, to listen to one another and to jam.

“The Dead’s philosophy was always very similar to ours,” Betts said. “We sound very different, because we're from different roots. They're from a folk music, jug band, and country thing. We're from an urban blues/jazz bag. We don't wait for it to happen; we make it happen. But we’ve always had a similar fan base and philosophy — keeping music honest and fun and trying to make it a transcendental experience for the audience.”

This is an excerpt from Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, Copyright 2023, Alan Paul. Click the title to order from Amazon or here to order a signed copy directly from me.

This is an adaptation from Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s It was my third straight book, following Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band – to debut in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List. His first book was Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about my experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band. It was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. I am also a guitarist and singer who fronts two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

Regarding Anji…Just to clarify

The song is an old traditional Irish tune played on an album by a guitar player named Davey Graham.. that’s where Paul Simon got that tune

Paul Simon played it on the sounds of silence lp which (I assume)

is where Duane heard it

Being handed a guitar from Jerry

That was quick thinking

on Duane’s part

I was at the Gaelic Park concert on the 17th. Right upfront by the stage. It was absolutely surreal. I was/am a huge Duane fan so I very emotional by just see his guitar on a stand. But when Jerry and the boys came on stage, it was heavenly..