Almost Famous

An interview with Cameron Crowe, one of my journalistic role models, about Almost Famous, Jerry Maguire, The Allman Brothers and much more.

Almost Famous: The Musical is having its final performance today, January 8. I am really sad that it is closing because I think it’s great. I saw it twice in getting ready to profile Cameron Crowe for The Wall Street Journal and was profoundly moved both times. Clearly, it is up my alley - a work of art exploring the themes of my life: love of family and music, journalism, the struggle to be both an insider and an impartial observer, etc. But the show resonated profoundly with my wife as well.

Cameron Crowe has been an inspiration to me since I started reading his work in Rolling Stone as a kid. At the time, I had no idea he was only about a decade older than me. His remarkable story of his career as a teen chronicler of rock and roll greats is pretty well known. I also told it in my WSJ story, which you can read here.

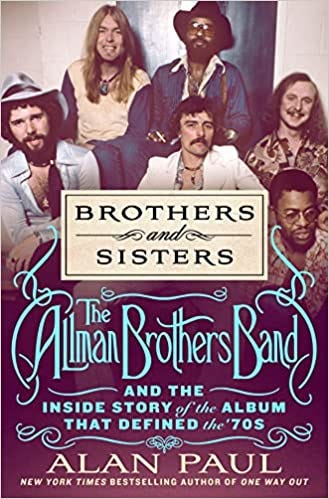

I interviewed Cameron a couple of times for my upcoming book, Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, in which I really tell the story of his experiences with the Allman Brothers Band in 1973 and how they became the basis for Almost Famous. In writing the book, I also relied on quite a few of CC’s articles as sources, including not only his RS cover story, but many other pieces for the magazine, as well as for Circus, Hit Parader and others. He wrote about the ABB a lot! Below are some highlights of two interviews I did with Cameron for the WSJ article.

As always, this article is free. If you enjoy it, please share and please subscribe to Low, Down and Dirty.

A few highlights of a phone interview, conducted shortly after I saw the play in previews.

Cameron Crowe: Hey, before we start, I have a question for you: was the location of Red Dog’s mushroom tattoo right to you? It’s on the chest and I sort of think it’s the ankle.

It’s actually mid calf on sort of the backside. I can send you a picture of Derek’s. This is one of the only instances in which my arcane knowledge of such things is actually useful, so I’m happy to be of service.

Journalism lives! That's all I can say. We're on it. [Note: The tattoo which the actor playing Red Dog proudly displays was moved from chest to calf. My Broadway contribution!]

Have you ever read Red Dog’s book, Book of Tails?

Of course, I love Book of Tails. It's so good. He sent me two signed copies.

How did you make the transition from being a journalist into a filmmaker, with Fast Times? Was it an ambition of yours?

No, it was really one step at a time. I always loved movies and I was on the set every day for Fast Times and in on all the auditions and rehearsals and everything. We hired Amy [Heckerling] to continue with a project that we had started with Art Linson, who I knew from being the president of Spin Dizzy Records and Nils Lofgren's manager. He made the transition into producing movies, which was wild. Never did I think directing would be a part of it - just writing a screenplay was already way past the original dream, which was to get a cover story in Rolling Stone.

I didn't even get the bug to direct while being so close to Amy and Art making Fast Times. It seemed daunting, like something you needed to go to film school for. But I did fall in love with screenwriting. I always loved the reviews of Jay Cocks in Time magazine. So rock journalism started to bleed into film criticism, which started to bleed into the idea of journalistic screenwriting. Again, over-answering your question, but it kind of mushed into the next stage and got to the point where I was writing the Say Anything screenplay for James Brooks. He was a journalist, too, and he was researching Broadcast News. Jim said, "You should write a script about a guy like you; you're an interesting character." That was the genesis of Lloyd and Say Anything and it was only when all these directors were turning us down that Jim said, "You know, if we get one more person turning this down, I advocate that you direct it yourself."

Lawrence Kasdan was one of the directors who turned it down, but he almost did it. He said, "If I wasn't ready to do Accidental Tourist, I would direct this." Which was mind blowing to me, and he came back and said, "I hear you may be directing this and I will support you at the studio to direct it." This was building, but the last person to turn down directing Say Anything did so with such strange gusto that it was kind of terrifying that I was going to actually direct it. I told Jim, "I don't know about blocking or how to arrange actors in the frame." And he said, "Oh, you'll pick that up. The most important thing is to remember to change your socks a couple times a day." Which of course was a ruse; changing socks did not help. You just kind of keep making mistakes and lumbering forward, but I got the bug.

About directing specifically?

Yeah. I really I got the bug doing the kitchen scene in Jerry Maguire with Renee Zellweger when she's watching Jonathan Lipnicki hug Tom Cruise. I called for a push in and I was playing “Secret Garden” in the kitchen, and it was like, galvanizing. I might have even gotten really emotional, but Janusz Kamiński, the cinematographer saying [imitates his voice], "Move along, move along, let's not get emotional about these things! Come on! It's just a little scene in the kitchen! Let's go!" But I was sitting there in the kitchen going, “This is what I want to do the rest of my life!” That's how it happened.

Wow. What were you thinking you were doing directing the movies before that?

Protecting the screenplay.

So that was a transition to thinking you were a filmmaker and not a journalist who makes a movie sometimes?

Absolutely. A filmmaker who's also a journalist, and some of my favorite filmmakers are that. Truffaut, Bogdanovich… there's a little bit of a tradition there that I was barely aware of. Billy Wilder started out as a journalist. So it was cool. Singles really was trying to capture an Almodovar kind of idea but it was more protecting a script until halfway through Jerry Maguire. Alan, it's such a cool thing that you asked me about this, because it really was just like after getting a cover story in Rolling Stone. What do you do when your early dream falls into place somehow? I just tried to keep going.

What was cool about it, to me, is it was all an opportunity to use music, from the very beginning, I was always playing music on the set, trying to direct with the songs playing during the scenes. And people were uncomfortable with it for a minute, and then they dropped into realizing that it changed the performances. There was a sound guy that came up to me and said early on, "You don't get it, man, it's like, you're gonna kill yourself in the editing room because you put music over the scenes where people are talking. So you're gonna have to go in and re record the dialogue. Unless you find a way to let the actor dance with the music and you cut the music off when he's about to speak." And I was like, that sounds like fun. So all the actors went with it, Alan, except one. Only one actor. And that was Philip Seymour Hoffman.

Right. Didn’t he basically say, "Don't tell me how to do my job, turn the music off"?

Absolutely - but a little angrier than your reading. He was instantaneously offended. He might have even taken me for a walk and said something like, “A real filmmaker wouldn't need a crutch." Some version of that. It was like, uh, okay. [laughs]. I guess not everybody is going to be down with this idea. But the guy who loved it the most was Tom Cruise.

Interesting. So Philip Seymour Hoffman wasn't just saying "I don't need this, turn it off." He was saying, "You're lame for needing it." Is that accurate?

More like, let me send you some homework from the University of Filmmakers because gotta learn to not use stuff like this if you're going to be a complete filmmaker. I remember he said the words "complete filmmaker."

Did that give you pause at all? Or did you just think, “Okay, this doesn't work for him, and I'm gonna continue doing it for the rest of my life”?

Both, because I still felt like if you're going to spend three or four years on a screenplay, protect the words in every way possible. So I guess in the world of a so called "complete filmmaker," you throw your script away sometimes and just follow your filmic instincts and I was not that guy. Yet. I became that guy. But at that point, it was a transition to just opening the aperture a little bit. Some people really use craft and the instinct, as well as the written word . I think he was just kind of a little erudite and crabby.

***

Interview at the Jacobs Theater on Almost Famous Press Day.

Someone here said that you were a good collaborator because you are still an interviewer at heart.

That’s super true

Have you always been aware of that or is that your natural process?

Totally natural process, like why not hear what’s on other people’s minds? So many people aren’t used to being listened to.

It’s an interesting dynamic here, because it’s a mostly young cast and it’s your personal story, but you’re still open to their input.

Why would I not be? This is not my first language. Live heater is its own thing and what’s cool is I haven’t gotten a lot of, “Kid, this is how we do it in the theater.” Which I did get in the movie world. This is much of a welcoming thing. Maybe it’s because I’m a newbie but people have been very open to me and willing to both teach and listen.

Right. But it’s interesting because you’re a theater newbie, but you have a very well-established track record in other realms, so it’s no longer, “Show me what you got kid.”

A little bit, but I’m always looking to learn and open to others’ ideas.

Do you still feel that when you make movies? Does that ever go away?

No, it never goes away.

So it’s you!

Maybe so, but you can always learn. It came from interviewing Billy Wilder and how curious he was. Who among us could have their ticket stamped more easily for I know my shit. I don’t need to learn anything else than Billy wilder. But he was endlessly curious. He interviewed people like crazy – another former journalist. I remember him saying that he didn’t want to die because he wanted to find out what happened to dolly, the sheep they cloned. It was amazing and I felt that he was a lesson to people on how to age. So, coming into this it’s like, “Yeah, teach me!” I’ll be cranky sometimes about wanting to protect what the original intention was, but mostly it’s like, “yeah, teach me!” It’s a collaboration.

Are you ever conflicted between what feels best for the show versus “My sister wouldn’t have said that, but it works better on stage”?

No. There’s not a lot of that in the show. Actually, she’s happier with her relationship with the mother in the play than the movie, because it’s tougher. And my sister did not have a starry eyed vision of our mom and hse doesn’t in the play. This communicates that relationship better, for sure. Everything that Anika [TK, who plays Mrs. Crowe] says are things that came directly from my mom. If it’s written for what I’m told a Broadway audience wants it will never be as true to the spirit of the story, so I just have to be honest and go with my instincts.

Is that how you’ve approached all your movies?

No. This more than anything because it is so personal and there are mostly real people being depicted, along with composites. I just think, I didn’t go too many Broadway shows. I went to Shakespeare at the old Globe when I was a kid, but I was not a musical theater brat or huge fan. My nieces are. I saw and loved Jersey Boys, but I knew this was not that kind of jukebox experience. I thought if there’s a way to do it that’s somewhere between a concert, something for a music audience, and something also for an OG theater crowd, and if they could come together, that would be cool.

Sometimes in a musical, it doesn’t feel right when a person starts singing. You think, “That person wouldn’t sing!” When the mother starts singing it could have felt like that, but it doesn’t! and I’m not sure how much that’s because of the actor, the song, the staging, or the combination of all that.

She did sing. She did sing, you know. She was musical in that way. Past tense is still weird.

I’m sorry.

No, man. It’s life. Believe me, this is making her happy.

Her problems began with a broken hip, right?

Yes. She didn’t want to go assisted living, she didn’t want to be looked down upon or hang out with people her own age. She’d still be here if she had gone with some version of assisted living. I think, Alan, the spark went out a little bit when she knew she couldn’t go to opening night at the Old Globe, that she would be denied that by her doctor.

My last conversation with her, I said, “It’s just six weeks. You can be there in six weeks and we’re going to play longer than that.” And she just went, “yeah, well…” she had a dream that she would be there with three seats every night because she was using a walker, but she had ll these young friends and she envisioned one on either side of her. Every time I saw her, she was like, “Three seats, right? Three seats!” so the fact that she wasn’t there for opening night was intense, but she was there. She’s still here. And the vast knew what I was going through, so we didn’t talk about it. We just talked about it.

Lester Bangs has a much more prominent role in the play than he did in the movie.

Yeah.

In the movie, he has prominent role, but not in terms of screenplay. He’s like the African drum of the movie, always there even when you can’t hear him.

Yeah, yeah, the drum is out front here. That’s a great way of saying it!

Thanks. It’s all yours. [laughs] Was that a very conscious decision, something you set out to do?

Yes. I wanted it to start with “It’s over” and have Lester saying, “You got here too late,” which is what he said to me. I wanted that to begin the story.

Is that what the guys at Rolling Stone thought when they were like, “Oh God, we don’t want to write about the Allman Brothers. Send the kid”?

Yeah, yeah. “It’s over.” For sure. Who’s gonna write about Jethro Tull? Let him. Because we want those Chrysalis Records ads. Yeah, that’s all real true.

…This kind of demanded a personal thing. Like Rob Colletti being Lester. I thought Philip Seymour Hoffman was the only guy who could do Lester by a long shot. Rob Colletti, same thing. With all due respect to anyone else who auditioned for Lester. Rob got it, and he reminds me of the actual Lester. That guy and the way he… his thing about Iggy Pop being part animal is the speech Lester was giving when I walked up and saw him in the flesh, on a radio show. I tried to get a tape of that radio interview and they fucking didn’t record it. It was with a DJ named Larry Yerden, and Lester was just on fire and that’s what he was talking about. Now it’s on a Broadway stage – it’s crazy!

Are the changes that you made from the movie to the play lingering things that had nagged you in the movie and you had a chance to redo?

No. Usually that would be true, but there’s something about the Almost Famous script. When it became that story told in that way, it was like “Leave it alone. Let’s not mess with it.” What I did want – and this may be perverse - is for Lester to be the master of ceremonies because I think he always had a little bit of a performance spark, like he was playing with his band there at the end. I just thought that would please my memory of Lester. That I got to do.

Did you know when you were first interacting with Lester that he was going to be a pivotal person in your life?

Yeah, yeah. He was bigger than life. He was bigger than life. Dickey was bigger than life in his own quiet way. And Twiggs [Lyndon] was bigger than life.

How was Dickey like that?

Dickey opened the door for me He ran out of stuff to talk about concerning the Indians and just kept talking. And then he was able to tell the other guys, “You can trust this guy.” And I honestly forgot that until I talked to Dickey again not all that long ago. He really remembered that and it’s true. Mike Hyland was like, “Dickey liked you. Give it a try.”

One thing I think about is what I must have been like for the Brothers when Gregg started wearing that white suit, and would show up with his entourage and that suit. That was kind of a little bit of whoosh. The layers, man. The layers that you don’t see even when you’re in the middle of it.

Alan Paul’s fourth book, Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, will be published July 25, 2023, by St. Martin’s Press. His last two books – Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band – debuted in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List. His first book was Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about his experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band. It was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. He is also a guitarist and singer who fronts two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

Appreciate the interview with Crowe. Loved the story of having Dickey's approval, lol.

Thank you for the stories💖