A little ditty about John Mellencamp. This is one of the best interviews I've ever done.

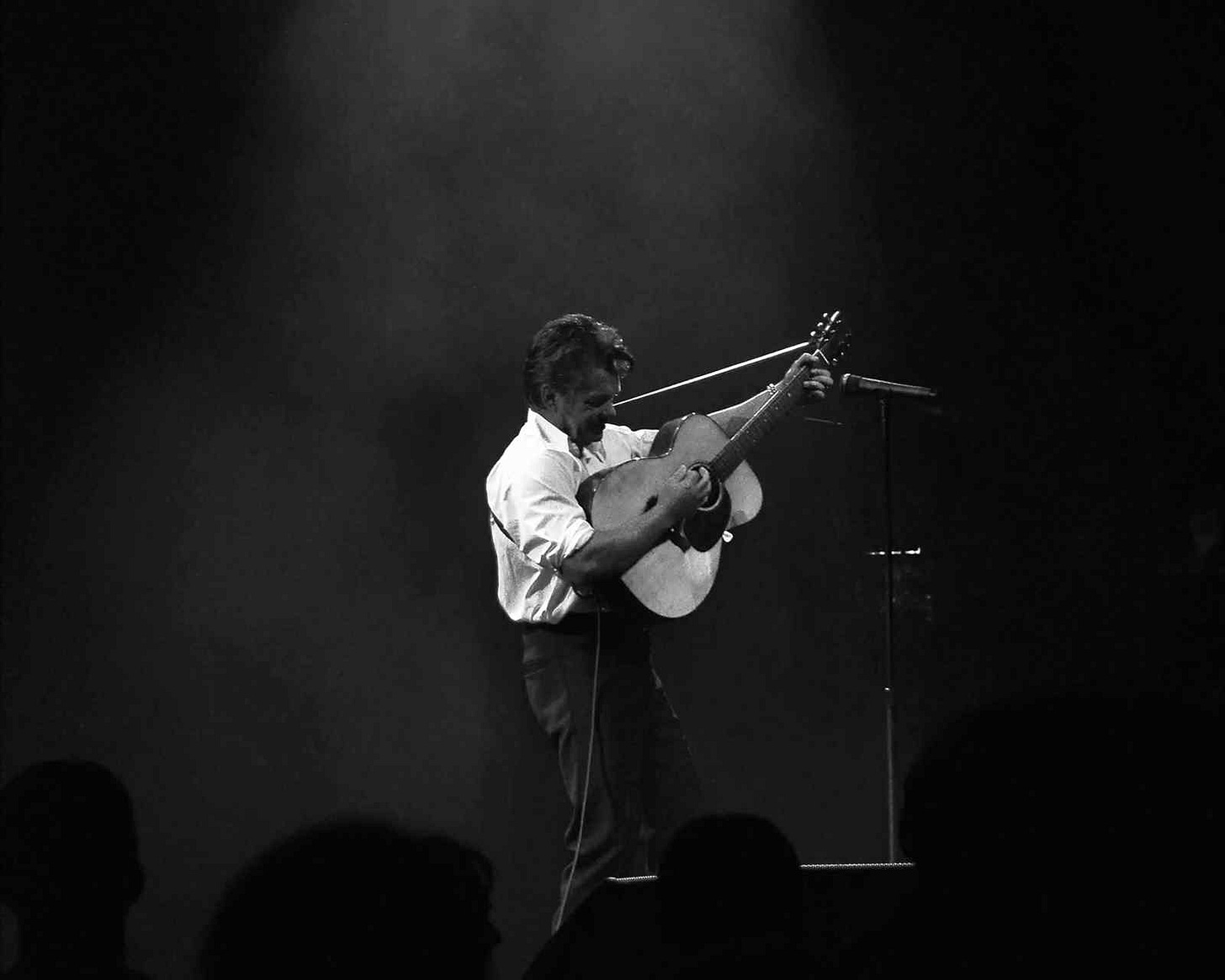

As I head into smokey New York City to see John Mellencamp, I wanted to share this extended interview with the man who hates being called "the voice of the heartland."

I interviewed John Mellencamp for The Wall Street Journal’s Weekend Confidential feature in 2021 around the release of his excellent album Strictly A One-Eyed Jack. The resulting story, which ran in January 2022, is here. I was really happy with it, but I still felt like it only scratched the surface of what we talked about I really feel like it’s one of the best interviews I’ve ever conducted, for a bunch of reasons. I am going to see John at the Beacon tonight, which finally prompted me to do a pretty light edit and share the extended Q and A below. Please let me know what you think.

Also, My obituary/tribute to Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Gary Rossington is up on Guitarworld.com and I think it’s really good. Check it out here.

This blog is always free and open to all, so if you enjoy it, please subscribe and share. And if you’re so inclined, feel free to preorder my book Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, which will be published July 25! And, while I have your attention, did you hear me on NPR’s All Things Considered talking about Jimmy Carter’s relationship with the Allman Brothers Band? You can listen here.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and relative brevity.

Your new record is powerful and the first thing we hear you say or sing, is "I Always Lie to Strangers," which sets a tone. Did you sequence it that way on purpose?

Of course we sequenced it that way on purpose. I still make albums, even though there's not a lot of demand for albums in today's world. I still look at albums as a piece of work. The average person hears something like 400 lies a day, and they tell 150. I found that quite astonishing, and reading that was the genesis of that song. We get lied to all the time, then we repeat what we hear, which is re-lying. I realize that I've grown up being lied to our entire life, by the government, by the church. But when you're young, you take it for granted that these things are true. It's not only do I always lie to strangers, but we always, all of us, lie to strangers.

That song has a pretty strong Tom Waits influence.

I would call it Nat King Cole. I love Tom Waits, don't get me wrong and I'm flattered that you would think that. But really boils down to I haven't been smoking all these cigarettes for all these years not to end up with a voice like that.

I'm not talking just about the vocal, but even the arrangement and the whole vibe. I had a similar feeling about “Gone Too Soon.”

That's just done in the American Songbook standard. You guys who write like to make comparisons, and I hate them, but if I had to, I would compare it to American Songbook or Chet Baker. I never understood why you would listen to a fucking record, then try to figure out what it sounds like. I never did that when I listened to records. I only cared about what the guy was saying and doing. The people who write... I don't know. And I'm not directing this at you, but it seems lazy.

It's okay, but let me flip it on you. Someone, maybe Frank Zappa, said, "writing about music is like dancing about architecture." Point taken, but it is a sort of ridiculous task, and we have to try to do it. So you have to give people some context. I certainly agree with you that some people do it in a lazier fashion than others, but we’re trying to use words to convey sounds and people need reference points. And the more you know about music, the broader the context you can provide.

Yeah. Listen, I don't know how old you are. But I don't even want to do an interview with the kids that's not at least 30. I've done interviews with younger guys. It was just like, there's no reason for us to have a conversation. Because we're on such different phases here in our lives.

How did the collaboration with Bruce come about now after you guys being very friendly for many years?

We've known each other for a long time. But we became pretty good friends about two years ago when we did a rainforest thing for Sting, and we had to play together. We just figured out at that point, that we connected in some fashion and now he's kinda like my brother.

Did you always feel a musical kinship with him?

Earlier records I did, but as time went on, I kind of lost track of him. I remember the first time I heard one of his records. I was in a head shop. You remember head shops?

I sure do.

Okay, I was in a head shop. And they were playing Greetings From Asbury Park. And I thought: 'Who is this mother fucker? He’s great.' I love his first couple records, and of course, Born to Run. After that, I started making records and was busy trying to figure out how to do that and I didn't really listen to a lot of music, especially my peers.

There’s no reason per se other than artistic to make an album now. The financial payoff is probably limited. But do you feel like this is what you have to do?

I have been very fortunate. I'll remind you, I started out as Johnny Cougar. And that was not a pleasant moment for me. I was 22 years old, being taken advantage of by a guy, like so many other young artists were. I really disliked the whole thing, but now I'm kind of grateful for it. Because that that gave me the chip on my shoulder that made me slug a little bit harder than the guy next to me. What started out as, for me, as how am I ever going to overcome this humiliation turned out to be what kept me going and slugging and kept me interested in becoming a better songwriter.

I started when I was 22. Now I'm 70 and still doing my job. Who would have ever predicted that? I've enjoyed an artist's life. I write and perform songs, which is art. I write, which is an art. I am a painter, which is an art. Being as lucky as I've been, the music business has given me the opportunity to really paint, which is really what I started out to do but got sidetracked for 45 years with music. So, I'm the luckiest guy of all the guys that started in rock bands. I had a big hurdle, and I was able to get over it.

That wasn't all luck! Anybody who's successful has good fortune and luck somewhere along the way, for sure. But obviously, it was also talent and that chip on your shoulder and the hard work in the hours put in. You agree with that, don't you?

Yeah. My term is this: luck is thinking you're lucky. I've always believed that. I was born with Spina bifida. And the fact that I'm even alive is pure luck. I've always thought that I was lucky. I had an operation in 1951, when they used to operate on people with shears and screwdrivers. They handed me over to my parents and said, "He's probably not going to live, he's going to be hydrocephalic. And he might live six months, he might not." I had the operation when I was six weeks old. I had a hole in my spine, at the base of my skull. I was born deformed, you know? In 1951, there were four other kids who were born with similar things at Riley's Children's Hospital -- they all died. I think that gave me a certain sensitivity because they had to cut my head off, basically and that's pretty traumatizing. I have the scar from one side of my neck to the other. I think all of that boils down to the sum of what kind of person I am.

You said that that experience with the bad manager at a young age put the chip on your shoulder, but wasn’t it already there? Would people who knew John Mellencamp at age 18 be surprised to find out that you had a chip on your shoulder?

I grew up in a small town and was involved in a lot of fist fights and the guys I hung around with, we were kind of dressed up hoodlums. I write on the new record, I don't mind a reasonable amount of trouble. In fact, I don't mind trouble at all. And I think that comes from my younger times. I wasn't afraid of getting in trouble. A lot of people edit themselves by going, “Oh, we'll get in trouble.'” I say, “All right. Fuck this, let's go.”

You have a quote from Nora Guthrie on your website. Is being part of the Woody Guthrie legacy important to you?

To be quite honest with you, I've never seen my website. I just have a couple who people take care of it, and they do what they think would be okay. Listen, I'm not for everybody. That's why the website doesn't matter to me. I had a bunch of hit records that I needed to have at that particular time in my career, but I've just never been for everybody's taste.

Your music or your personality?

All of the above, but I've written songs that have been for everybody. And thank God for that. Me, personally, I don't accommodate anybody. That’s what a good neighbor is. A good neighbor leaves your neighbor alone and if he asks for help, then you help them if you can. The rest of the time you just mind your own fuckin' business.

It’s funny you mention that because a friend of mine has a friend who is actually your neighbor and told me that they all love you because you do things like plow their driveways. You're considered a great neighbor! That was the specific phrase that came back to me: “Everyone thinks John is a great neighbor.”

That's because I don't fuck with them and they don't mess with me. Yeah, I do things quietly for people, but I don't want any credit for just trying to live as close to the golden rule as you can get. I interpret the golden rule in a lenient fashion. Sometimes I'm into this side of it and sometimes I'm into that side of it.

In the mid 80s, popular music had a certain sound, with mushy drums and everything sounding synthetic. Stevie Ray Vaughan, who I wrote a book about, helped kick down that door, but so did American Fool. It had a big, crisp drum sound and your musical approach was stripped down. It opened up what could be on the radio. Does that make sense to you?

Yeah, it does. Everybody was playing in drum booths, and I hated that sound. We made that record at Criteria in Miami and we did all kinds of crazy shit to get that drum sound. Engineers had got to the point where it's like, give them the old number 87…this is how you mic a drum kit. I went, "No, no, no, we're not doing that." And it was a whole big fucking discussion and argument with engineers about the way records were made. We used all kinds of different types of mic techniques and experimented to get that drum sound. We wanted something that sounded like it was in the living room, not pushed back in the background. And that drum sound made Kenny Aronoff one of the most sought-after drummers. But it took forever. We’d been down there for two months and the president of the record company came down and we only had three songs done because we kept fuckin' around with the sound of the drums. And he absolutely shit. He went, "Are you kidding me? This sounds like hell. This is not what we want from you. We want you to become the next Neil Diamond with your songwriting."

He literally said we want you to be the next Neil Diamond?

Oh, yeah. That pissed me off wild.

Wow, it's really off base. I'm sorry to interrupt you. That just stopped me in my tracks.

Neil Diamond did write some good songs.

Absolutely. But I just don't hear it as...

Yeah, I couldn't hear it as my future either. So we had three songs done in and back then record companies paid. I didn't have any fucking money, and they were tired of paying for it only to have three songs. But those three songs were "Jack & Diane," "Hurts So Good," and "A Hand to Hold Onto" -- all top ten records. The president of the record company hated them all.

But the good thing that came out of it is that it was Record of the Year and I never had to fuck with the record company again, ever. I remember saying to the president of the record company after he told me that he hated it, "Hey, look, it's not your fucking job to like or judge what I'm doing. It's your job to sell the fucking record. So why don't you do your job, and I'll do my job."

And so how did you get from that point, where you only had three songs, the record company is furious at you...

Well, once we found the drum sound, things moved!

How confident were you? These three songs were huge hits that changed your life and career, but did you have a sense of that?

No. Matter of fact, doing something simple is much more difficult than doing a lot of arrangements. I'm happy that we're having this conversation because you're one of the first guys in my career who recognized the fact of how simple that record is. And to make a record that simple, everything has got to be performed properly. "Hurts So Good" sounds simple. [sings riff] And it is, but to play something that simple in time, and have it feel like it's in your living room is an impossible fucking feat. Now that is a juvenile song to be sure. It’s not that great, but I was a juvenile when I wrote it. [laughs] We cut that song 100 times. Day after day after day, we cut it, and we just couldn't get it, because we were cutting live and all it took was the drummer to fall behind on the drumbeat, or the guitar player to fuck something up or me to come in a beat early. Because there's only two guitars, bass and drums, and maybe an organ part in the bridge. And that drum sound! I've had a lot of people tell me that the first time they heard "Hurts So Good" on the radio, they pulled the fuckin' car over and went: "What the fuck is this?" I always took that as a compliment. You pulled your car over to listen to it?

That's the greatest compliment! But you were saying it's a juvenile song. After all these years, do you think, "Well, maybe it's not that lyrically complex, but it has something that people connect to and relate to." That's not an easy thing to do.

The one that really surprises me is "Jack & Diane." Because that song was just impossible to make. "Jack & Diane" are arguably the most famous couple in rock history, right up there with Frankie and Johnny and it’s astonishing to me. That song today makes more money than it did when it was number one. Isn't that unbelievable? I don't gauge things on money, but are you shitting me?

That's another song that sounds so simple, but is trickier than it seems. Isn’t the hand clap thing actually a LinnDrum machine?

It was a prototype that I borrowed from the Bee Gees! The Bee Gees were making a record in there and I'd walk by their session and I would hear the sound and I'd go 'What the fuck is making that sound?' So I asked the engineer Albhy Galuten what it was and he told me and I was like what the fuck's a LinnDrum machine? Then I asked if I could borrow it. Everybody thought Kenny was the greatest drummer in the world, but Kenny always rushed songs. You would start out at one tempo and by the time you got to the end of the song, he'd sped the song up so much I couldn't hardly sing it because it was going so fast. The drum machine did not speed up or slow down, so we put that in "Jack & Diane" just so that we could keep time-- with the full intention of taking the LinnDrum machine out of the song.

You were using it as a click track.

Yeah. And back then using click tracks was frowned upon and looked at as cheating. So we took the LinnDrum machine off "Jack & Diane" and the whole fucking song went away. And that's why if you listen to that song, you only hear the drums come in in that one section. The rest of it's in the drum machine.

Mick Ronson also had helped arrange the song, right?

Yeah, Mick was great. We had the same manager and became very good friends.

Which is amazing: two people that the general public really wouldn't associate with one another.

Yeah. But Ronson was from a small town in England and was just a very talented guitar player and arranger. I called him up and said, "Ronson, you need to come down and help us because we're floundering." He played on my very first record - we had been friends from the get go because we both found ourselves in a very peculiar place. Neither one of us had any fucking money, which is hard to believe, because without Ronson, Bowie was only half of Bowie. I asked him to come to Florida and help with arrangements and he said, "Okay, Johnny!" I picked him up at the airport, and he still had on his fucking show shoes from David Bowie, because he didn't have money; he had all his clothes in a paper bag. He heard the song and goes: "You know, Johnny, we need to put some baby rattles on here." And I go "What the fuck are you talking about?" But if you listen to that record, there's baby rattles. And it was his idea to put that big, "let it rock, let it roll" with very little instrumentation. Yeah, Mick was a great guy. I still miss him to this day.

He contributed so much to David Bowie and to Lou Reed. As I understand, he was the guy behind "Walk on the Wild Side."

Mick Ronson was one of the most talented guys in rock history, and when Bowie hired him, he was cutting grass. He was a yard guy. I loved Mick and right before he died, we brought him out on tour with us in a wheelchair. He's the only guy I ever saw in my life that got drunk and fell asleep standing up. We all lived together in a big house down in Miami, and we left him standing in a doorway and woke up the next morning, and he was still standing there, but sound asleep.

When you were a young guy going to New York banging on doors and bringing demos around, what was your confidence level? What did you think was gonna happen?

I was rejected by every record company in the world, but it really didn't have to do with my confidence. I just thought they were wrong. In college, every weekend, they would have these concerts of local talents. And I would stand out in the audience and go 'These fuckin' guys aren't any good. I can do better than that.' So when I got my first record deal, I thought that was the end of it. I know that sounds crazy, but that was my goal, and I thought that was the end of it. That’s how much I didn't know about the music business. I just figured that every record that got made got played and I’d make a couple. That’s the way it looked to me being an avid music fan then; you made a couple of records, then you went away. That’s what happened to The Mamas and the Papas, Leon Russell. Fucking Bob Dylan was 35 years old, and they were already looking for the next Bob Dylan. When Bruce was “the next Bob Dylan,’” Bob was only 33! And the record company had already discarded him. They wouldn't allow Bruce to put electric guitars on those first three records because he was supposed to be a folk singer.

Right. Stevie Van Zandt says because Bruce got signed as a folk singer and showed up in the studio with the band, including Clarence Clemons. Stevie showed up and they said, "Who the fuck is this guy? You got a saxophone player and now you have another lead guitar player? Get him out of here." He wasn't on the first two records.

Yeah, because they could only have acoustic guitars. When Bruce told me that, I went "Fuck, I didn't even notice there wasn't any of that." The only thing I noticed was how clumsy the drummer was. But that clumsy drumming made those songs.

It's an interesting dynamic. You got infamous for being a difficult bandleader and demanding perfection, but Bruce got lovingly named The Boss for it. Do you think that's part of the skill?

Yes, and Bruce or myself didn't hold a candle to James Brown, who was the largest taskmaster, ever. I can't speak for Bruce, but I knew that while other guys were at nightclubs, getting drunk and high, we were rehearsing, trying to learn how to be the best that we could be. Because we knew that we were shits that weren't that good and had to work harder. I knew that I needed to have hit records because rock critics weren't going to support me. We had to go the old Motown way. Motown was all about fucking hit records. They used to call the Supremes the No Hit Supremes until "Baby Love."

Was there a point where you quit thinking that way?

No, I still think that way. I'm more of the Woody Guthrie vein, because ultimately, and finally, I don't give a fuck. I never did look for acceptance. And that's what most people don’t understand. I don't need applause. I've had enough applause. Think about it: If you're playing a show, and people applaud, what the fuck did you think they were going to do? They just paid money to come see you. They're not really applauding you as much as they are applauding themselves for being there. And I think that's great.

I'm processing that. But you've played thousands of performances and you know the difference between really connecting with the crowd and not. It feels different.

Well, here's the thing: 15 years ago: I was so sick and tired of playing in arenas, and stadiums occasionally, because I was playing to the gallery and I hated that. So I made a decision much to the disappointment of the people who were handling me that I'm only going to play theaters from here on out. I have to have a connection with the audience, or else I'm just not going to play and you guys are out of fuckin' luck. So get used to the idea: Mellencamp is only going to fucking play in theaters. That's the only place you can play to the front row. Because if you're playing in an arena, there's a barrier between you and the audience. And yes, they'll sing along with the hits, but they're there to party and to drink and have fun. It's a celebration. I'm not there to celebrate. I'm there for the music. If you look at Dylan's early shows, or Pete Seeger's early shows, people are sitting down listening to the songs. Almost in amazement that they're hearing what they're hearing. That's what I was always going for. Not 'let's have a fuckin' party, let's have fistfights.' I remember starting shows and the minute I started, a fist fight would break out in the front row. What the fuck? This is not what I'm here to do.

But you really wanted people to be sitting and listening even when you were a young rocker?

Oh yeah. I'll be very lowbrow about the whole thing: a guy can be standing in the front row where he paid top dollar to come see John Mellencamp and celebrate the fact that he's there and a pretty girl can come up, walk up to him and go, "Let's go outside and get in my car." He's gone. You follow me?

Yeah.

Doesn't take much for them to lose interest in John Mellencamp and the ticket that they just bought. Because it's human nature. Let's be honest, if you have a chance to go make out with a beautiful girl in her car or sit there and watch me sing "Small Town," what are you going to do?

Well, "Small Town" might be there the next night and she might not...

That's right. [laughs] She may not. So that's the importance of a lot of performance. if you witnessed Newport and all of that music, people were sitting on the edge of the chairs, watching Janis Joplin, in awe of the music. That was always my goal. You can't have that in an arena,. And I have played in front of 80,000 -- the biggest crowd I played in front of was 120,000 people. You can't have that there.

Well it's a different thing. I saw Bob Dylan just a couple of weeks ago at the Beacon, and it was incredible. Very much like going to the theater or symphony -- sitting and being attentive and the music is almost like chamber music. It's not really improvised, it's very controlled, but it's just beautiful. His voice is incredible. The arrangements are spectacular. It was great. Not just good, great.

I went to see Bob and felt the same way, but I felt that the tour before this was better, just perfect I did a tour with Bob and Willie Nelson, and we did like 100 shows together, playing outdoors in ballparks and that I saw people staying for me and leaving the minute Bob came on stage. I thought, ‘They're staying just to hear these fucking hit records of mine and Bob's not playing hit records.' It was during those shows that I decided I was done playing outside. I'm done playing to the gallery. I don't care about the money. I got enough money. This isn't about the money for me.

Does it mess with your head to have a standing ovation the moment you walk on stage? You’re supposed to work for it! That’s always felt weird to me, though I’ve certainly had the feeling of just being thrilled to be in the room with an artist I love so much,

If you look up what applause is supposed to be, applause is supposed to be from the angels for a magnificent job done. And, when I walk on stage and, people are all applauding, it's kind of like, “I haven't done anything. What are you applauding for?' The only thing I can figure is they're applauding my history, and the fact that they're there, because I haven't done shit.

It’s also a reflection of how much your music has impacted them. When they see you, they see Jack and Diane, and it takes them back to their own summer romance, and it means a lot to them. That's not a small thing.

I understand that, and I love "Jack & Diane" now because of that and I used to not like it, but as I've gotten older, I love the fact that they do that. But I cannot repeat himself over and over again. There's the art of performance, which I separate out as the art of writing songs. When you saw Bob, he played a lot of songs that were new. He didn't play "All Along the Watchtower" or "Like a Rolling Stone” and I admire that he has the courage to do that. Because if Bob wanted to, he could be just like The Rolling Stones. He could walk out with an acoustic guitar in a stadium and played "Blowin' in the Wind" and, "Like a Rolling Stone" and all the rest of his incredible songs. He could be playing stadiums, but he chooses not to. And for that, I have to take my hat off to him, because Bob is a real artist. He's not there for the money or the applause. Because the applause, again -- I know I sound like a broken record -- it's just bullshit.

What's the flipside of that though? If you finish performing a song and people didn't applaud, how would you feel standing on stage naked without it?

You're nobody until you’ve been get booed off stage.

John, when was the last time you got booed off stage? It's been a while.

It was in Oakland, in 1978. Got booed off, I made it through two songs.

Were you opening for somebody?

Yeah. They didn't give a fuck about me. Bill Graham didn't give a shit. People act like Bill Graham was some great guy. Fuck Bill Graham.

What was your beef with Bill Graham?

I had beef with every promoter. I'm a hard guy to deal with, because ultimately and finally, like I said, I don't give a fuck. And I never have. I never cared about my parents’ thoughts, never cared about what my teachers thought, I never cared what the football coach thought. Never cared and I don't know why. Maybe because of this operation had made me put up a guard, maybe I'm too sensitive and to keep from being touched. I have this huge fucking wall built around me and it doesn't matter to me. You can say what the fuck ever you want. And ultimately I don't care.

Have you changed at all in that regard as you've gotten older?

There's no way to cut it: I'm old. [laughs] I'm very isolated. I live an isolated life. If you look at all my paintings, the characters are always isolated. I'm working on a big painting right now and it's four by eight with just one little guy in the middle of this big canvas. I think I have a song called "The isolation of Mr." Maybe it's a painting, I don't remember. I've made something like 27, 28 albums. For a guy who started out thinking if I had two records, I'd be doing good.

Well, your recent records are really good, so kudos to you. As you've mentioned earlier, you know, if you didn't feel like you were doing good work or had something to say, there'd be no point in making the records. I get that, but they're very strong. Your last few are really good and they're different. You're not repeating yourself.

A lot of people don't love John Mellencamp records, but they like them, and that is surprising to me. Because when I had a lot of hit records, I learned a lot of lessons about that, and I just didn't like playing that game. I don't know how old you are, but we grew up in a situation that was a lie. We believed that who we listen to is who we are: I like R.E.M. so that makes me a certain kind of person. It really doesn't. It really has no reflection. You wrote a book about Stevie Ray Vaughn, but if most people really knew where Stevie Ray Vaughn came from, they would scratch their head.

I tried to illustrate that, but point taken. Our music worlds were very tribal: "I'm not gonna listen to Led Zeppelin because those guys are over there smoking cigarettes listening to Led Zeppelin and that's not me. I'm not gonna listen to R.E.M. because it's those dorks over there”… whatever. I get what you're saying, and I feel like one of the advantages of streaming music is that's broken down a little bit. I hear my kids listening to things that shock me because they just are open and they don't connect the music to tribes in the same way we did.

They don't connect them with tribes at all. I've got two boys that are in their early 20s and they don't care. They're reacting to Johnny Cash to Biggie Smalls, whatever. They don't care. It doesn't tell them at all who they are; they just like the song.

How important has Farm Aid been to you?

It’s surprising to me that we're still doing it. I don't think that Neil, Willie, or I visualized that. I don't know how many years that is. So many it makes your head hurt to count that far. Makes my head spin dizzy. I don't think any of us really knew what would happen and that it would go on. Farm Aid has done a lot of good on a very small level with individuals, but as far as the government goes, I don't think that we've made much of an impact with the government and their understanding of what it means to not -- look, Ronald Reagan changed everything when he deregulized [sic] everything. He fucked everything up. And I wrote a song once called "Country Gentlemen," and Reagan wasn't even President anymore. And I was talking to ...what the fuck's his name... the guy that used to be the main critic at the LA Times, Bob [Hilburn]. And he asked me, he goes, "Why are you writing a song about Ronald Reagan? He's not President anymore." I said, "Bob: the politics that this guy has put into place, we will not see the effect of until we're older people." And I think that now we're seeing it: the rich are extremely rich, and the poor are extremely poor, and there's no middle class. All of that goes back to Reagan and him deregulizing [sic] everything. The fucking guy was just full of shit. It was just about rich people. That's why I don't understand why working people are Republicans, I just don't get it. And your paper...

I don't work for the Wall Street Journal! I am freelance, but point taken. Maybe partly because of your political views, you never really liked being called the voice of the heartland. Do you just find that lazy or do you find it not true?

The voice of the heartland, I think, is a band like REO Speedwagon. I'm not the voice of the fuckin' heartland. I'm the most liberal fucking guy you’re gonna talk to. I told Barack Obama, when he asked me to support him: "You're not liberal enough for me."

That being the case, does it make you uncomfortable to live your whole life in such a red part of the country?

I could give a fuck, because nobody says anything to me about it. They know better. Nobody wants to argue with me.

Do you still smoke?

Yeah, I'm smoking right now.

I read that you said, "Well, I've just come to feel that this is gonna kill me. So whatever." Is that accurate?

Well, actually, yes, and no. I said that about 15 years ago. I said, "Yeah, I still smoke and I had a heart attack, but I believe that if you smoke and you become sedative -- sedative, that's not the right word.

Sedentary.

Sedentary, yeah, that Your lungs will… I just had an MRI on my lungs and they look like they're fucking from a teenager. I work out every day. I run and lift weights every day. I still run wind sprints at least once a week. Now, I admit that you have to drive the stake to make sure I'm moving. But nevertheless, I don't know any other 70 year old guys that are out doing wind sprints.

Do you ever think about or care about the fact that you seem to have been like a really big influencer on Americana music? On "Cherry Bomb,” you used fiddle and accordion, and dulcimer, alternative instrumentation that was quite influential.

We didn't do it for that reason. I was working with a producer who hated the fuckin' fact that we were doing that and that was my last record I made with the guy because I had to fight with him. "Let's put a banjo in there," and it's like "Nah." My guitar player Mike and my engineer Dave Leonard re-mixing Scarecrow now with today's technology and it's amazing to me. I'm not involved in it, but it is almost like a brand new record now, because you hear stuff. If that record came out today by Keith Urban, it'd be a number one country record.

Has this been something you’ve wanted to do for a long time?

No. When they told me that the record company wanted it -- because it's been like 50 years or 45 years or some shit, I said "I don't care. You guys do what you want." I don't go backwards. That record is old and I don't care. But I was surprised when they started sending me mixes. I heard a song called "Minutes to Memories" and went, "Jesus Christ. I wish we had that mix on it 45 years ago because it's beautiful. You guys are doing great."

Another thing you share with Bob is the painting. This is really important to you, right? It's not like a little side hobby.

I do it every day. Las night I painted til 10 o'clock. I put in 12 hours just with a painting. I got to give a lot of credit to Bob, because I was painting and Bob came to the studio back in the 80s, because I directed a video for Bob. He came to my studio and goes "What are you going to do with all this?" I went "Fuck, I don't know." He goes "why don't you try to sell them?" And I go "Who the fuck would want to buy this crap?" And he said, "Well, I sell mine." He gave me the idea that somebody would want to buy these things. And they did.

Did that make you take the process more seriously?

I was always serious about it. I went to New York to try to see how much it would cost and what was involved with going to the New York Art Student League. At the same time, I had demo tapes, and it turned out that record companies wanted to give me money and the art student league wanted me to pay money.

In an alternate reality where money was not a factor, would you have gone to art school at that point?

I went to school, and I have a degree in journalism. And I found out real quick that I didn't want to do that. [laughs]

You went to Vincennes College, right?

Yeah, it was a place for like, really stupid kids.

I'm sure that's not true.

It was a junior college, but any college that I would have gone to, I would have had to go in and be put on probation. Why? Because I didn't give a fuck. I had dyslexia and back then they just thought you couldn't read. Dyslexia is not what people think it is. For me anyway, you can take a word like "Wait”: W-A-I-T. I've read that word one million times, but then sometimes I'll be writing and I go, wait, how the fuck do you spell that? And I have to ask somebody that works from here: How do you spell 'Wait', they go W-E-I-G-H-T or W-A-I -- and see that's the fuckin problem. With dyslexia, all these different words that are the same words with different meanings ger mixed up in your heard, and it's confusing. Even though I know the difference between weight and wait.

Bob Weir has very severe dyslexia. And went through a similar thing as you, of course, where people thought he was stupid or couldn’t read, and he credits it with helping him just come up with these kind of crazy chord inversions. Because he didn't look at things in quite the same linear fashion.

Yeah, it makes you figure out different ways of getting stuff accomplished, rather than the traditional way. Like, I know more about Steinbeck and Tennessee Williams than probably most people, and it's taken me all of these years to read them. But I figured out real early that if I watched the movie and listened to the dialogue it makes sense -and half the fuckin' songs I've written I've stolen lines out of those movies. John Prine said it to me best. He goes, "Wouldn't you just give a fucking million dollars to somebody that listens to the lyrics to one of your songs?" I go "Yeah, I get it John." Because they just don't listen. I don't know what the fuck they're listening to but they're not listening to the lyrics to my songs, because if they did they'd get it. But they don't.

I think with both you and John, many people listen to your lyrics. Like you said, you're not always writing for the masses so maybe not everyone, but certainly enough people. One last thing: on the songs where there's only guitar, and voice, who's playing the guitar? Is that you?

Andy York or myself. And maybe Mike Wanchic. It all depends who's got the best feel for the song. Whoever's got the right strum. A great thing that Andy did is that he learned how to strum like me. Because my problem is that I'm used to accompanying myself on acoustic guitar, and I'll do what Bob does, or what Woody would do. I may leave out a couple chords and not even play them and just sing the melody and then just stay on that chord. If there was a guy that played guitar worse than me, it was Woody. I'm a terrible guitar player. Fuckin' terrible. The guys in the band begged me not to play ‘cause they got to play along with me and not with the drummer. They would rather play along with the drummer because they're professional musicians, they want to keep time. And I don't do that.

Hey, that's the gig. You play bass with Lightnin Hopkins, you make that change when he does, not when you feel it should come.

That's right. And that's the way I play. When I write songs, we have to organize some because one time a verse will have this many chords in it and will change and then the next verse, it'll be the same melody, but the chords won't be the same. It’s being not schooled, and not really being a musician.

The funniest story ever was Janis Ian wanted me to produce a song for her a long time ago, and we sat at the piano with her and she kept putting these passing chords in and I go "What the fuck are these passing chords?" The same thing happened with Arlo Guthrie. We were doing "This Land Is Your Land" and rehearsing it at soundcheck and I go "Arlo, what the fuck is with these passing chords?" He goes, "That's the way the song goes." I go, "No, it's not. Your dad didn't play it that way." He goes "Yeah, that's the way dad played it." I said "No, he didn't put no fucking passing chords in.” He goes "I've always played it with passing chords." I said, "I've never played it with passing chords. So can we just play it, but the way your dad would play it and not the way that you would play it?" And Arlo started laughing, he goes "Okay, we'll do it your way." It was better to fucking do it the way I wanted to do it than argue with me about it.

Well, John, thank you very much. I appreciate the generosity of time and really enjoyed talking to you and thanks for all the music. It's been part of my life for many years, and it's a pleasure to get to understand it a little bit better.

Well, I appreciate it and just try not to make me sound too much of an idiot.

I always try to capture the essence of the person. I don't think you're remotely an idiot. So don't worry about that.

Alan Paul’s fourth book, Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, will be published July 25, 2023, by St. Martin’s Press. His last two books – Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band – debuted in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List. His first book was Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about his experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band. It was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. He is also a guitarist and singer who fronts two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

Terrific interview. Really enjoyed it although I was never in the camp of knowing much about Mellencamp beyond his radio hits, all enjoyable and catchy. I’m not sure what to make about his persona; he comes across as a bit of a cranky old geezer but his passion and seriousness for his art (music and painting) and yearning to connect with his audience is evident. I didn’t know he painted and went to check it out. I was impressed by his evident influence by the Austrian Expressionist and obvious homage(s) to Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt. Your interview also brought out the difficulty in being a serious musician who tours relentlessly for the live gig where the lyrics and music (should) mean something beyond playing to just another packed-in beer crowd and audience chatter. I’m thinking that’s why Springsteen so coveted his solo story and performance dates. I note that Mellencamp also went from initially dismissing your conversation as just a necessary interview with an uniformed music critic to respect and real engagement. Nice work!

Wow- I read this and you have risen several steps on the pedestal Alan. He’s a curmudgeon ( imho) and you kept your cool and persisted to get a terrific interview. Kudos!!!