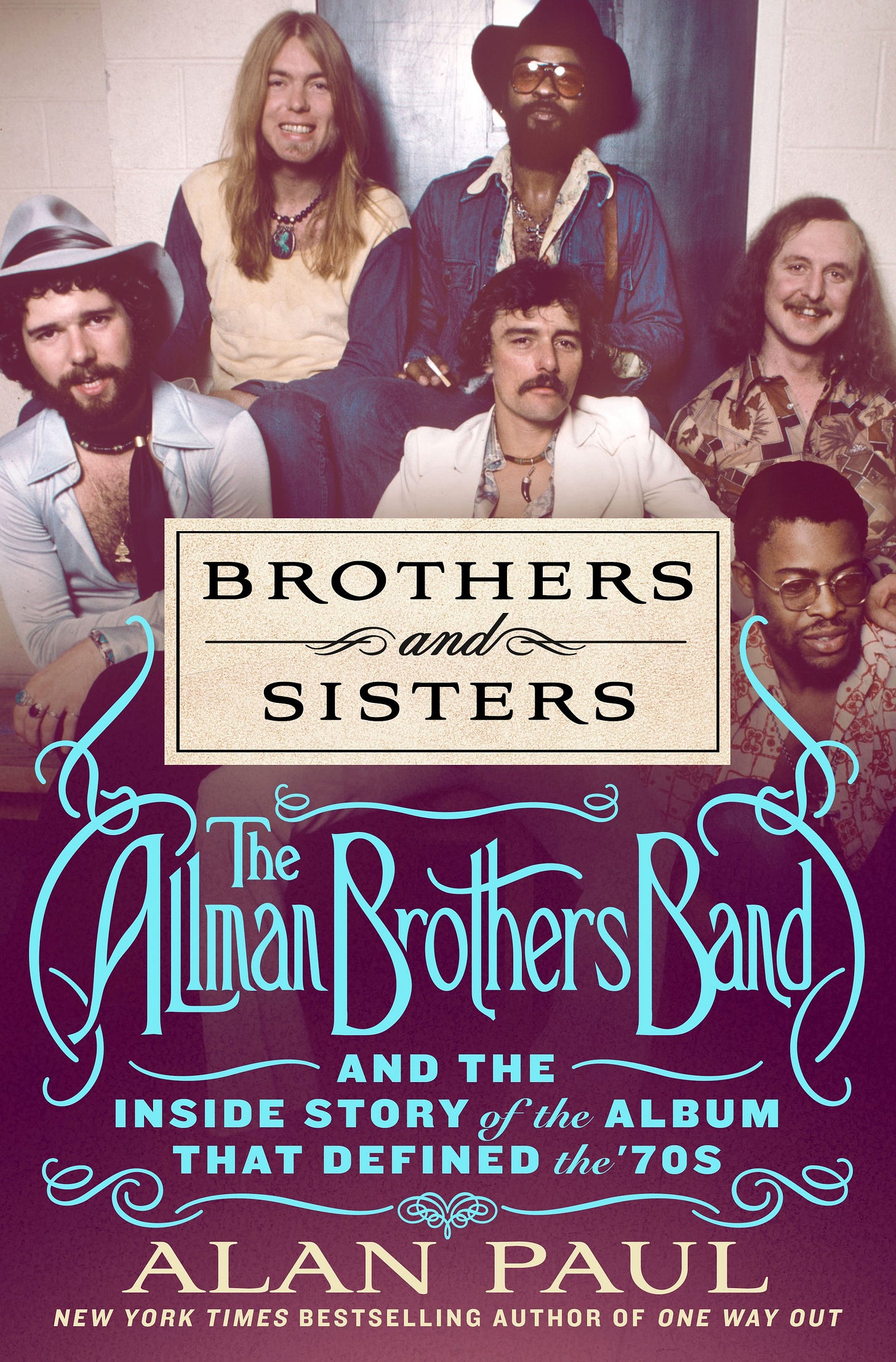

50 years ago today: The Summer Jam at Watkins Glen: a Brothers and Sisters excerpt.

The two chapters on Watkins Glen are amongst my favorite in "Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s." I adapted them here to celebrate the 50th anniversary.

I’m really proud of the two chapter on the Summer Jam at Watkins Glen, which celebrates its 50th anniversary today. The book is off to a great start. You’re gonna want it, and if so doing it this week is really helpful to the author - me! You can buy it anywhere books are sold, including Amazon, of course. Signed copies are available via Words or The Big House Museum. Words copies can be personalized. Put that info in the comments section. Also, I did a great interview for an in-works documentary on the Jam. Please check out their Kickstarter here.

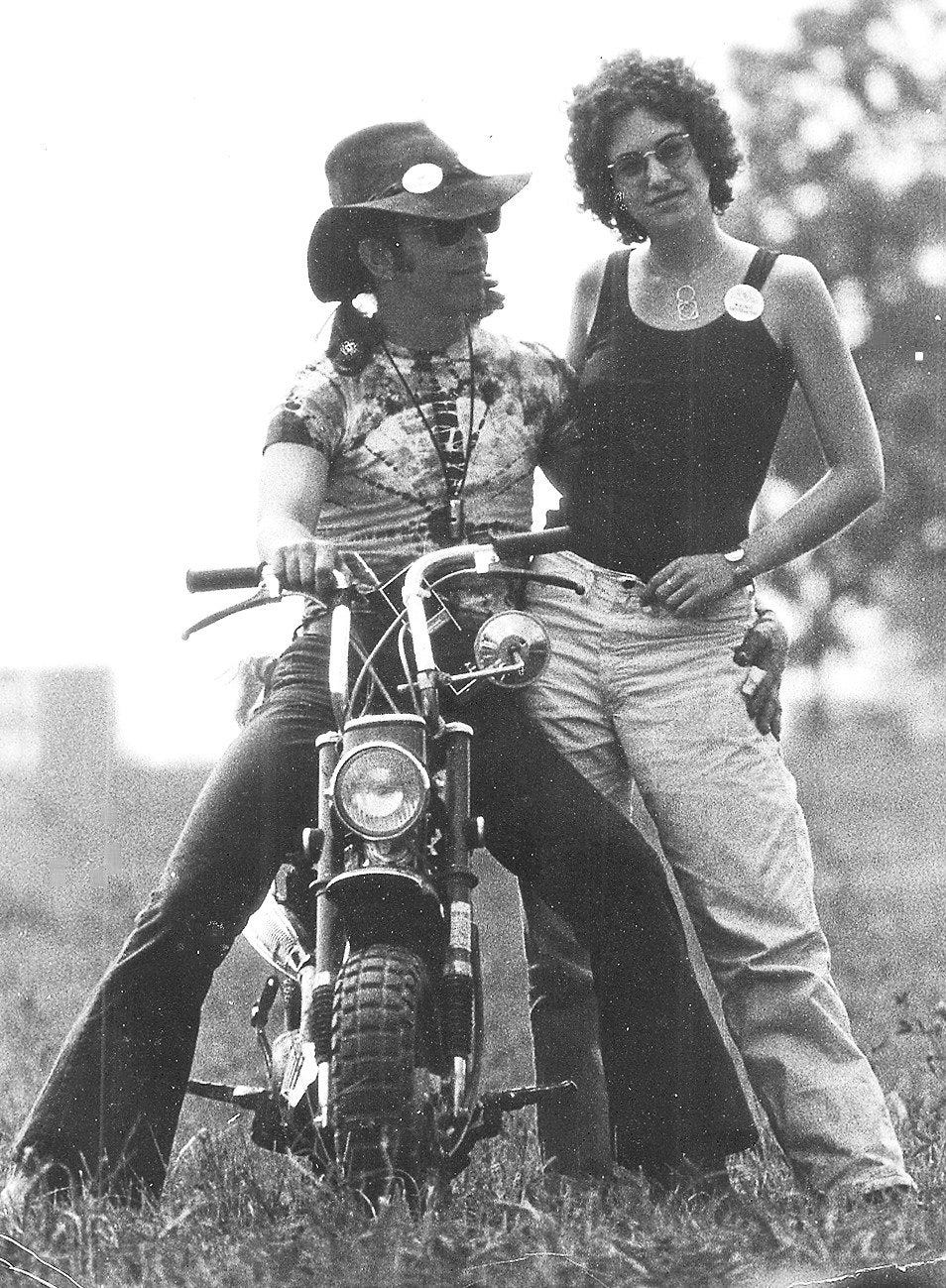

The largest rock festival in American history was held 50 years ago, on July 28, 1973, when the Summer Jam at Watkins Glen drew a crowd of about 650,000 to New York’s remote Finger Lakes region to see the Allman Brothers Band, the Grateful Dead and the Band. There were 50 percent more people at the Summer Jam than had attended Woodstock, four years earlier and 150 [CE1] miles to the east. It is estimated that 30 percent of people between the ages of 17 and 24 living between Boston and New York were there, as well as one of every 350 Americans. Yet the Jam never attained the same cultural resonance as its smaller, more famous cousin in part because the Dead refused to allow filming or recording. Still, Watkins Glen showed the power of the burgeoning youth culture, and the increasingly mainstream status of the Dead and Allman Brothers Band. Each group felt like the other proved that their regional appeal could be replicated nationally.

“The Allman Brothers Band represented the Southern tribe of freaks,” says Sam Cutler, then the Grateful Dead’s co-manager and of the driving forces to making Watkins Glen happen, along with Allman Brothers Band day-to-day manager Bunky Odom and promoters Jim Koplik and Shelly Finkel.

Cutler says he was trying to “take the band to a much larger space, to the national fan base we knew was out there.” Odom had similar visions of what the Dead could do for the Allman Brothers. As the managers looked at tapping one another’s fan bases, the musicians simply enjoyed one another’s company and any opportunity to interact, to listen to one another and to jam.

“The Dead’s philosophy was always very similar to ours,” Allman brothers band guitarist Dickey Betts says. “We sound very different, because we're from different roots. They're from a folk music, jug band, and country thing. We're from an urban blues/jazz bag. We don't wait for it to happen; we make it happen. But we’ve always had a similar fan base and philosophy — keeping music honest and fun and trying to make it a transcendental experience for the audience.”

Just six weeks earlier, the two bands had drawn about 83,000 people over two nights to Washington DC’s RFK Stadium

.

Koplik and Finkel knew from the start there would have to be a third act to create a real festival vibe and do away with the tensions around which of them would open and close. The promoters signed a contract with Leon Russell, but when Jerry Garcia insisted that The Band should be the third act, the promoters gladly agreed, sure they would turn down the offer, having not performed in eighteen months. When they surprisingly accepted, Koplik had to cancel Russell, whose contract was for the same amount.

The promoters sold about 200,000 tickets for ten dollars, but in the days before the festival, it started to become clear that the crowd would be far larger. As the Grateful Dead sound team worked to build a massive sound system that was a precursor of their Wall of Sound, people were streaming to the festival grounds, lining up behind the closed gates for day.

Koplik and Finkel huddled with Bill Graham, who was hired to build the stage and backstage areas and decided to open the gates a day early to help keep things calm. By Friday, July 27, over 200,000 people were already on the grounds, with thousands more flooding in by the hour. Even as the fields around the festival site filled up, the small country roads leading to the concert site became literal parking lots, as travelers abandoned their vehicles and walked miles to the concert.

Seventeen-year-old Andy Aledort and a friend hitchhiked 200 miles to the festival, joining the masses walking the last stretch. The guitarist, who would go on to play with Dickey Betts for ten years (and who is my coauthor of Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan) says that it wasn’t lost on anyone that the Jam was becoming something much larger than anticipated and that the explosion was a result of people like him - teenagers who were too young to attend Woodstock but old enough to be fully aware while it was happening. “We wanted our own event and that’s why it became so big,” he says. “We wanted in!”

Brad Perkins was a nineteen-year-old army radio operator who traveled to the Jam with three friends and discovered the “biggest drug market on the planet,” he recalls. On the long walk from the gate to the stage are, they traded homemade wooden pipes they had brought for “for good pot, opium, speed, and LSD.”

Helicopters were summoned to ferry the bands. As they drew close to the site, the passengers asked the pilot to circle the area, their minds blown by the sea of humanity stretched out beneath them.

“We wanted to soak it in and it was absolutely stunning to see this ocean of bodies,” recalled ABB keyboardist Chuck Leavell.

Rain had delayed the completion of constructing the stage and the planned sound checks had never taken place. It was a problem with 200,000 people already on site 24 hours before the concert was to begin, but Graham saw an opportunity and suggested that making the soundchecks public performances would help keep things calm. He rightly anticipated that the bands would more than say “Check one, check two.” The Dead played about two hours, followed by the Band, who played an hour, and then the Allman Brothers, who also performed a two-hour set. The one-day festival had organically doubled in length. The Dead delivered a signature, epic performance that has resonated for half a century.

People continued streaming toward the grounds, creating the very real threat that fences could come down, resulting in a stampede or other unsafe situation.

“I was frantic because we had really lost control of the gates and I was worried about the stage,” said Koplik. “Bill told me that we had to open the gates and abandon ticketing or else the fences would come down and many people would be hurt. It was momentarily a difficult decision but clearly the right one.”

While all this was developing, Koplik says, the bands were all happily ensconced in the comfortable backstage, complete with palm trees, swimming pools and a volleyball court.

“Instead of being drug free, it was free drugs,” says Koplik. “We had a trailer with free coke and pot. It was quite festive, with naked women running around.” The bands, he says, got along great” and hung out together all day.

Meanwhile, the crowd just kept growing, filling Watkins Glen camping in people’s yards, bathing in rivers, dropping acid and sitting on rocks staring into space, searching for friends, meeting future spouses, getting separated from their crew, and doing everything else you can imagine vast hordes of young people doing.

As the Dead was preparing to take the stage on July 28, Cutler approached Koplik and demanded an additional twenty-five thousand dollars in cash, making it clear that the band would not take the stage without it. His logic was that the agreed-upon fee had been struck based on an expected crowd of 150,000–200,000 and there were many times more than that in attendance.

“I tried to explain that the additional people were there for free and we hadn’t made a dime off of them, but he was not persuaded,” recalled Koplik.

Koplik and Finkel retreated to their trailer and pulled twenty-five thousand dollars out of a safe, which they handed to Cutler in a bag. With that, the Grateful Dead took the stage and the promoters thought they had dodged a bullet, but another financial confrontation was looming. As the Dead played, a helicopter bearing ABB manager Phil Walden landed backstage. Without even knowing that an equal-pay agreement had been violated with the additional payment to the Dead, Walden took one look at the massive audience and determined that his band would either be getting more money or packing up their gear and heading south.

“When Phil found out it was now a free concert and we didn’t know how many tickets had been sold, he exploded,” recalls Odom.

Odom assured Walden that they could work out the situation, while also quietly telling his road crew that they should be prepared to take everything off the stage and load it onto their equipment truck—or at least make sure the promoters knew they were ready to do so. Odom then found Finkel and Koplik, and the three of them sat down in the back of a limousine to discuss the problem and the fact that Walden was ready to pull the band if they didn’t receive more money considering the giant crowd.

“I pushed them on how many tickets they had actually sold and they admitted they had enough money,” says Odom. “Once I could assure Phil that we were going to be paid more, he agreed to let the band play.”

Though there were no reports of significant violence at Watkins Glen, there was one death, but it occurred in the air, not on the grounds. Veteran skydiver Willard Smith jumped out of an airplane with others. Looking to make a big impression, he was armed with an “artillery simulator,” which is similar to a hand grenade and designed to create a large boom. It seems to have detonated on him, causing massive chest injuries, and his lifeless body floated into a tree about a half mile from the stage. The other abiding tragedy of the event involved Mitchel Weiser and Bonnie Bickwit, Brooklyn teen lovers who disappeared hitchhiking to the jam, a case that has never been solved.

During the jam itself, each of the bands performed long sets. The Dead, opening because Garcia offered to – defusing any tension before it could develop - took the stage at 12:20 pm, opened with “Bertha” and played for four hours. The sound check performance was indeed more powerful.

The Band started their performance at 5:00 pm under low clouds, threatening skies, and increasing humidity. As they were finishing their eighth song, the skies opened and the band ran off the stage, instruments in hand, as the crowd was drenched by rain.

Most of the Band stood on the side of the stage passing a bottle of Glenfiddich single malt scotch. and contemplating the likelihood of Watkins Glen devolving into “another Woodstock-style mud bath.” Keyboardist Garth Hudson took a few long pulls from the bottle and suddenly sent roadies scrambling to move plastic sheeting as he took to his instruments and improvised some cosmic classical blues.

Hudson’s swirling improvisations morphed into “The Genetic Method,” which he took to the edge of outer space, paving the way for a dramatic return to the stage by the entire band, who synced up with Hudson and segued into “Chest Fever.”

The Allman Brothers Band’s festival closing set started at 9:30 PM and included five songs from the still-unreleased Brothers And Sisters. The large puddle in front of the stage filled with mud-slicked dancers as the band delivered an excellent, lengthy set.

After the Allman Brothers wrapped up their three-hour set with “Whipping Post,” they returned to the stage with most members from the other two bands in tow. The combined groups played an extended encore of “Not Fade Away,” “Mountain Jam,” and “Johnny B. Goode.” “The jam at the end was spectacularly wiggy,” recalls Grateful Dead guitarist Bob Weir.

The police worked with the departing masses to help them get out safely, even trying to arrange rides for some of the kids heading out on foot. The next morning, the streets of Watkins Glen were filled with bedraggled, muddy youth walking around after emerging from spending the night in 24-hour laundromats and anywhere else they could find shelter. More kids lined every nearby highway and byway holding signs for their intended destinations, including Florida, Ann Arbor, Montreal, and Cape Cod. In their wake, they left behind a sea of trash.

The New York Times escribed the site as a “giant garbage dump,” where the debris was so thick that the ground was not visible. Rolling Stone’s Joel Siegal wrote that the scene looked like a “war had been fought there. A war fought with beer cans and plastic water jugs, whiskey bottles and Cracker Jack boxes and 10,000 jars of Skippy Peanut Butter.”

Garcia took a helicopter directly to Mount Holly, New Jersey, where he faced charges stemming from a March stop on the New Jersey Turnpike, when he and lyricist Robert Hunter were pulled over for speeding. While opening his briefcase to procure his driver’s license, small amounts of marijuana, LSD, and cocaine were revealed, resulting in a search of his briefcase. Garcia signed autographs and chatted with reporters outside the courthouse, then received a suspended one-year sentence, the charges to be dropped after that time if he avoided further criminal charges.

The Allman Brothers returned home to Macon, Georgia after the

Summer Jam, almost a month before their next show and before the release of Brothers and Sisters and “Ramblin’ Man,” which would soon become their first hit single. The event, Melody Maker noted, had elevated them to “rock royalty.”

Writing in Crawdaddy, Patrick Snyder-Scumpy wrote, “Watkins Glen was not a place to come hear music,” but to “be with the music in an environment that epitomized its message.”

This is an adaptation from Brothers and Sisters: the Allman Brothers Band and The Album That Defined The 70s, was published this week. Alan Paul’s last two books – Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band – debuted in the New York Times Non-Fiction Hardcover Bestsellers List. His first book was Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, about his experiences raising a family in Beijing and touring China with a popular original blues band. It was optioned for a movie by Ivan Reitman’s Montecito Productions. He is also a guitarist and singer who fronts two bands, Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, the premier celebration of the Allman Brothers Band.

Congratulations on the book's release. I have ordered my autographed copy from Words, your hometown bookstore. I will ask my fellow 649,999 Watkins Glen attendees to do the same!

I just read the chapters in your book! Terrific. So much more detail than previously written. I went to Watkins Glen and can testify it was a chaotic scene. The NY State Thruway was stopped! Folks passing joints between cars simply by sticking a hand out the window. We abandoned the car miles from the racetrack and I slept in a cornfield. I have a vague memory of music in the night. Sound check? Saturday was hot then wet then humid. Seeing the stage was a Herculean task but sure, the sound was good. A parachuter appeared and a giant flare ignited and later, we learned he was a fatality. Food was scarce but the freaks shared. We stayed through the Band and despite my love for the Brothers (had recently caught them in March or May on Long Island), and my indifference to The Dead, we knew leaving would be a nightmare. So yeah, adios. My pal and I packed up and bid a muddy adieu to Watkins Glen. Funny, I left my camera in the car so have only one pic of the road out but I still have my unused, unripped Ticketron “Summer Jam” ticket! $10 well spent. Ha. Every Allman fan needs this book and I’m purposely putting it down so as to not finish it fast.